Exploring the ‘Aesthetics of Excess’

Jillian Hernandez highlights the styles of Black and Latina women and girls

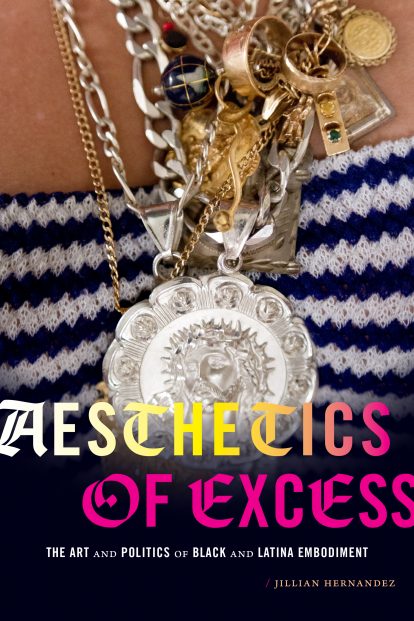

In November 2020, Jillian Hernandez published her first book, Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment (Duke University Press). An assistant professor in the Center for Gender, Sexualities and Women’s Studies Research, Hernandez used the book to explore how working-class Black and Latina girls and women are often framed as embodying “excessive” styles — styles that, while sometimes mocked, are nonetheless often appropriated by contemporary art and pop culture.

(Video by Peyton McElaney and Pristina Kuo)

Hernandez, who recently was selected for placement on the Fulbright Specialist Roster and received a Getty Scholars Residential Grant, used her experience working in a community art setting in North Miami to inform her analysis in the book. After earning her undergraduate degree at Florida International University in art history, Hernandez went to work as an educator at the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami. Given the assignment of expanding the local outreach programming for the museum, Hernandez connected with an often-neglected audience.

“This was in the early 2000s when there was a growing number of girls entering the juvenile justice system in Florida,” she said. “I immediately thought that would be an important space to do some outreach work and use art to connect with the girls that were incarcerated, to just give them a space to process what’s going on, to have conversations about identity, gender and sexuality.”

Hernandez quickly realized how large of an impact this outreach could have, observing that the incarcerated girls and young women had only a small selection of donated books and DVDs to keep themselves entertained — and they were not entertained.

“Bringing in art as a tool to spark conversation and connect was just really powerful,” she said.

There is a history to why certain ways of putting the body together are viewed as tasteful or not tasteful. And these ideas of style are not frivolous at all.

Ultimately, this outreach led Hernandez to found Women on the Rise!, an official program through the museum with the goal of using contemporary art to “inspire girls to engage in critical dialogues about body image, relationships, and culture through hands-on art projects, visits to exhibitions, and meetings with noted women artists.”

The experience was incredibly rewarding for Hernandez, but also led her to examine her own place within the contemporary art field, along with how it can often turn a mocking eye toward the girls and young women she was engaging.

“As a working-class Latina, I was very much an outsider within the museum space,” she said. “I would witness the girls’ bodies being talked about really negatively by teachers or by corrections officers or the girls talking really negatively about each other’s bodies. So the question of the body and how it mediated a lot of these power dynamics, both between the girls but also between the girls and the adults, became just something I really wanted to understand better.”

Deciding to pursue a graduate and then doctoral degree, Hernandez was disappointed to find that the literature she was interested in studying — on girlhood and issues of embodiment of gender, sexuality and race — was “very much focused on middle-class white girls,” she said.

In short, there was nothing that could speak to the experiences of the girls and young women Hernandez had been working with for years.

“I started to witness the ways in which Black and Latina girls were being represented in popular culture and how their bodies were valued through viral YouTube videos or contemporary art — valued in ways that in their everyday lives, these girls’ embodiments placed them in situations in which they were subject to discipline or mockery or othering,” she said. “How does this work? How is it that in one space, this very same look or this very same form of embodiment puts you at risk for derision, disciplining? Yet when this very same embodiment is in a museum and a work by an artist or in a funny YouTube video, that’s okay.”

Aesthetics of Excess is Hernandez’s attempt to try and answer these questions. In the book, Hernandez analyzes the cultural practices around how Black and Latina women dress and style themselves and how they are often marginalized — as the book’s description notes, “Heavy makeup, gaudy jewelry, dramatic hairstyles, and clothes that are considered cheap, fake, too short, too tight, or too masculine: working-class Black and Latina girls and women are often framed as embodying ‘excessive’ styles that are presumed to indicate sexual deviance.”

Hernandez notes that this marginalizing view can be traced back to European colonialism, where colonizers would encounter Indigenous people that they assumed were less intelligent than them and whose aesthetics were vastly different. The Europeans used these aesthetic values to further fuel their preconceived racist notions.

“There is a history to why certain ways of putting the body together are viewed as tasteful or not tasteful,” Hernandez said. “And these ideas of style are not frivolous at all. They actually structure what we come to understand as race and gender.”

With the Aesthetics of Excess, Hernandez hopes to shine a light on the girls and women she worked with through Women on the Rise! and amplify their voices.

“The process of turning it into the book was me continuing to follow the girls. It’s all about what I learn from them and highlighting their voices as theory,” she said. “Women on the Rise! is still the most rewarding work I have ever done — I don’t think I will ever have an experience as rewarding as that.”