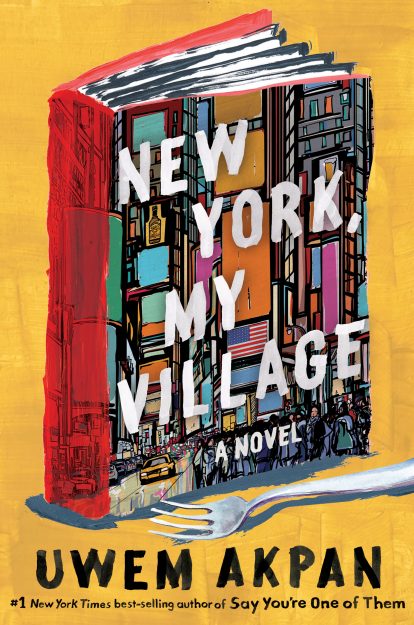

Q&A: Professor Uwem Akpan on His New Novel, ‘New York, My Village’

The book follows a Nigerian editor's move to the United States

Uwem Akpan’s short story collection Say You’re One of Them (Little, Brown) captured the literary world’s attention in 2008. A #1 New York Times bestseller, the book was selected by the Oprah Winfrey Book Club. It received a PEN Open Book Award and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, along with enthusiastic reviews.

Now an assistant professor of creative writing professor at UF (opens in new tab), Akpan has followed up his success with a thoughtful and intimate first novel. New York, My Village (opens in new tab) (W.W. Norton) follows Nigerian editor Ekong Udousoro as he moves to Manhattan for a fellowship granted for his expertise on the Biafran War. Ekong is determined to reveal the beauty in humanity, while navigating the complexities of white-dominant office culture, learning about African American and immigrant experiences, and dealing with a bedbug-infested apartment. Over 5,000 miles from home, he can only cling to patience and hope.

With its delicate observation of the tribalism in both countries, the novel offers readers a glimpse into the clash of ignorance and empathy found throughout the world. Celeste Ng, author of Little Fires Everywhere, calls New York, My Village a “rare thing: a funhouse mirror that reflects back the truth.”

Akpan discussed his new novel, his own experience arriving in the United States, and his approach to capturing people of different backgrounds.

In what ways did your experience of moving to the United States mirror your protagonist Ekong’s story?

In 1993, I came from Nigeria to the Bronx for two weeks, then began college in Omaha, Nebraska. So that first semester was not easy at all for me. There were a lot of changes. For example, in Nigeria by 7 p.m. it’s dark. It doesn’t matter the time of year — it’s just dark. But I was lucky: I was living with very good people, and the people of Nebraska were very down-to-earth.

In 2013-14, I lived in Manhattan as a Cullman Fellow of the New York Public Library. It allowed me to research for this satire of a novel. So situating this story in New York City means I’m taking some of my experience of coming to America and putting it in Ekong. New York is funny because nobody talks to anybody. It’s the classic idea of being lonely in a crowd. It was easy for me to plug what I learned or experienced about racism into my characters.

What characteristics did you find important to give your protagonist, Ekong?

I wanted someone who could talk about race from not just as a Black person but as a Black alien in America. It was important that as a character, Ekong is a very pleasant person — someone peaceful, someone with hopes and dreams with his rage hidden inside. The other characters are not aware of half of what’s happening in his head. He’s going nuts. That’s the kind of dynamics I try to work with: what [life] must be like for a Black person. For example, what is it like to be the only Black student in a UF class, even if everyone is nice?

In your last book, children were the central figure of each story. In this novel, Ekong’s niece Ujai is a prominent character. What about a child’s perspective intrigues you?

I was happy to find some continuity from what I did before. The sweetness and innocence the girl brought gravitas to the story because I could do a lot with it and write more about police brutality. The important thing is, we as adults want to protect the children. We don’t want to tell them everything. But sometimes, they’ll see it. The irony is that children themselves can tap into that and hide to protect the adult. No child wants to see the parent cry or fret. Sometimes, they’ll confide in the teacher at school or, in this case in Uncle Ekong.

What do you take into consideration when writing about a diverse group of characters?

I try to create complex characters. Everyone in this world is both a victim and an oppressor. We have to slow down and reflect, to ensure we’re not hurting others even as we’re hurting. The mistakes we sometimes make are a theme in my novel – thinking ‘I am a victim, I cannot oppress anyone.’ No, you can. I try to write to make it inclusive; everyone is a part of everyone else.

Why did you wish to include a variety of minority groups when portraying racism in the novel?

I wanted to write a diverse book that deals with what we are facing now in our world. I wanted so many people to relate to this story. The character Molly, for example, is feeling this complex thing inside because while she looks white, she knows she is a minority. She’s got privilege and she knows it; it hurts her; it shames her. She has to confront this before she opens the door for minorities in her publishing house.

Can someone apologize and can we accept the person? If you have a friend not from your group, what are the chances that person will not make a mistake once in a while? Is the person ready to grow? How big are these mistakes? If we cannot learn from our friends, where do we turn then? But having collided with Ekong, Molly’s now very determined to join the minority fight. So, in a big way, the novel is an invitation to all of us that we could do a bit better. We have to do better.

Learn more about New York, My Village (opens in new tab).

This story appears in the fall 2021 issue of Ytori magazine. Read more stories from the issue.