Photo obtained from a NewsBank archive

A Racial Reckoning in Gainesville

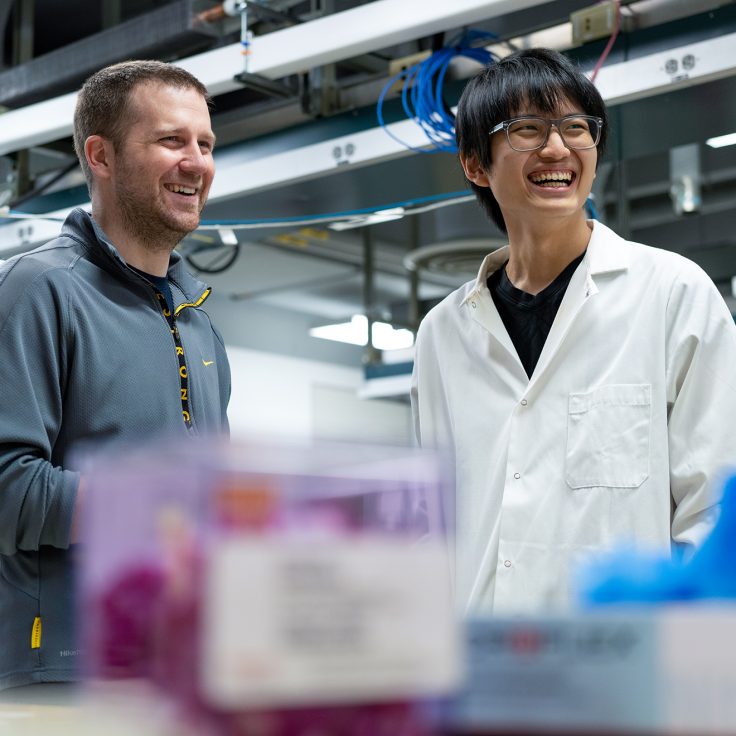

Samuel Proctor Oral History Program leads exploration of historical injustices

It has been a season of reckoning for historical injustices in and around the campus of the University of Florida, led in part by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Graduate students uncovered a 1920 article in which a Gainesville newspaper editor acknowledged membership in the Ku Klux Klan and other published accounts that contributed to the climate of racist terrorism following the end of Reconstruction and the emergence of Jim Crow policies.

Their findings, along with a presentation on the report of a presidential task force, a film premiere, lesson plans for K-12 classrooms, and accounts of experiences of antiracism activists in North Central Florida, were part of a series titled “Challenging Racism at UF” that ran from Jan. 14 to April 21.

“In oral history, we learn about the power of storytelling. This reveals truths that can sometimes be very uncomfortable,” said PAUL ORTIZ, history professor and director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. “We’re not trying to denigrate institutions — we love the University of Florida. But if we’re going to be a top-tier research institution, we need to use the tools of historical research to make the university a more welcoming place.”

“It’s great that our students have done this research and produced these materials that will allow others to write dissertations and senior thesis projects, but we’re not really doing our jobs if we’re not sharing this material with the public,” Ortiz said. “And that relationship with the public is a reciprocal exchange of knowledge.”

Investigation into how the local newspaper, The Gainesville Sun, reported on racial violence during Jim Crow came at the suggestion of editors at the newspaper, who enlisted the Oral History Program along with community members to underscore transparency. The findings were presented on Jan. 14 at the Cotton Club Museum in Gainesville. The Cotton Club Museum has been restored from a building with its own history as a social gathering spot for Black residents during Jim Crow.

“We admire originality,” opens an editorial in The Daily Sun, a precursor to The Gainesville Sun, on Dec. 16, 1920. “We abominate imitation. There was a time, shortly following the close of the Civil War and during the days of Reconstruction, when Southern men, in defense of themselves and their wives and children, felt compelled to organize that mystic order which has gone into history as the Ku Klux Klan.”

“This editor was a member of that order,” editor Robert D. Davis wrote without apology, except to assert that the number of murders had been overstated. “It was simply that all murders and all lawlessness was charged on account of the Ku Klux. It was the mystery about them, the midnight, the white sheets, the parades and a few discreet killings that produced the terror they were designed to produce.”

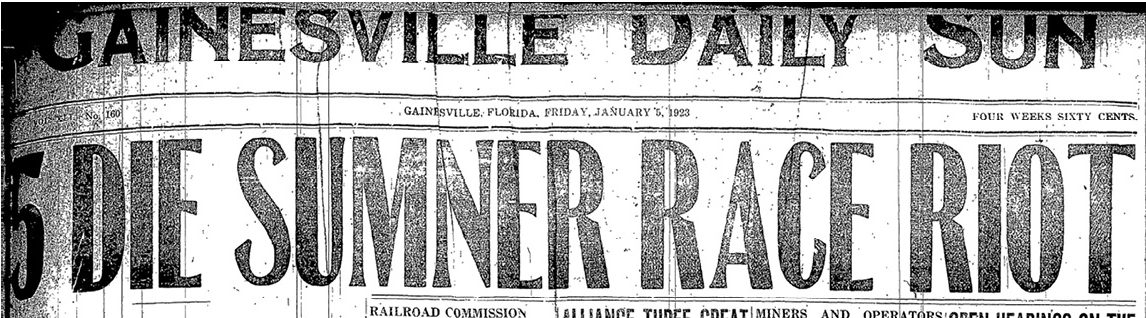

On Jan. 1, 1923, a woman was allegedly assaulted in Sumner, a town about 45 miles southwest of Gainesville. The assailants were supposedly two Black men who had barged into her house, although historians doubt the details as they were reported at the time. It led to the destruction by a white mob of a nearby town called Rosewood and the massacre of at least six but as many as 150 of its Black residents.

An editorial five days later included this: “We feel too indignant just now to write with calm judgment and we shall wait a little while. One thing, however, we shall say now — in whatever state it may be, law or no law, courts or no courts — as long as criminal assaults on innocent women continue, lynch law will prevail and blood will be shed.”

Ortiz spoke at the community presentation on the Oral History Program’s research and noted, “This is an appalling history — it is the story of one newspaper in the South that played an integral role in creating and maintaining white supremacy.”

“In one sense, this newspaper is like many newspapers in the South at the time,” he said. “The Gainesville Sun is one of a small but growing number of newspapers that want to come clean and be honest about its role in creating one-party rule, voter suppression and anti-Black violence.”

Ortiz observed that overcoming challenges like racial bias isn’t an inevitable, consistent march through time. “You take some steps forward and then a couple of steps back. The arc of progress doesn’t happen without a lot of work,” he said.

“We need the Oral History Program to research and preserve Black history, but it’s also important that we make sure these materials are accessible,” Ortiz said.

Explore the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program here.