Ancient civilization in Peru offers lessons on water stewardship

UF archeologist unearths the Chimú civilization’s quest to harness the lifeline in the desert

On the sun-kissed western coast of South America, nestled in modern-day Peru’s northern expanse, lies a mesmerizing testament to human ingenuity and the resilience of a once-mighty civilization. Around 900 A.D., this area was the home to the Chimú people and their Kingdom of Chimor, the second-largest empire in ancient Andean history. For over 500 years, the Chimú’s innovative spirit and technological prowess allowed them to transform the desert into a thriving oasis.

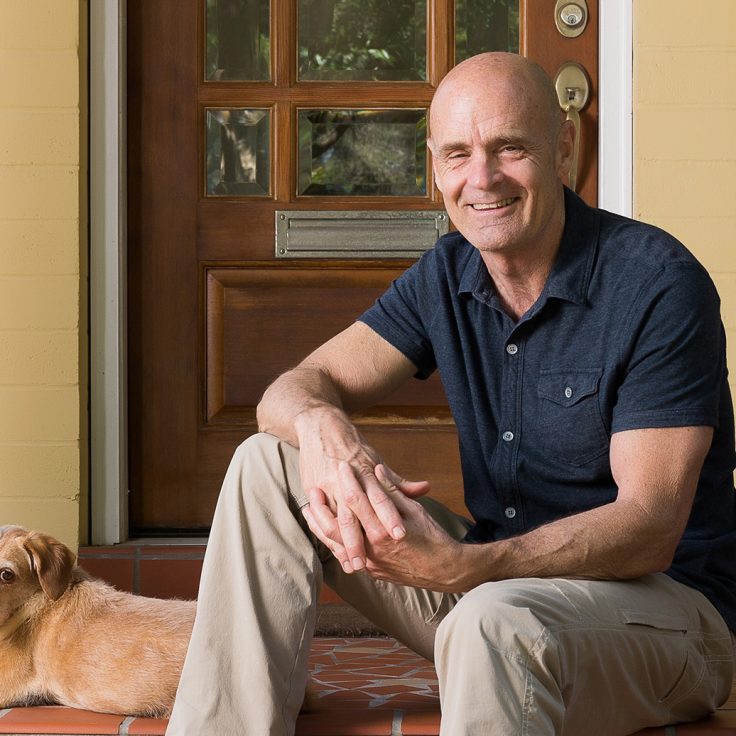

Despite succumbing to an eventual Incan conquest, the ruins of the Chimú endure, drawing global interest. Archaeologist GABRIEL PRIETO has dedicated nearly a decade to studying the Chimú people, fascinated with their relationship with the environment.

Prieto’s quest is to expand our knowledge of the development of early civilizations and dispel the myth that Indigenous people in the Americas were less advanced than their European and Asian counterparts. To that end, his work has uncovered a deluge of evidence that the Chimú were adept architects, farmers, and seafarers; some of their achievements rival and even surpass European advancements of the time.

The story of the Chimú and their efforts to control the water in their surroundings reflects humanity’s enduring and complex relationship with water. Like the Chimú, we are always trying to understand this precious resource and maximize our use of it.

“Chimú society valued water and invested countless resources to improve water quality and efficiency, both for their benefit and the environment,” Prieto said. “It was also clear that they were aware of the almighty power and destructive effects of water. Yet amazingly, they learned to not only cope with their situation but to take advantage of it, for the benefit of their society.”

Impressive Infrastructure

What sets the Chimú’s rise to prominence apart is their defiance of the limitations posed by their surroundings to build their oasis in the desert. The engineering feats they accomplished highlight their ingenuity, particularly in their resourceful use of limited freshwater sources.

The biggest challenge faced by the Chimú was sustaining their massive population, estimated to have peaked somewhere between 50,000 and 60,000 people in their capital city alone. Farming in the desert is no easy feat, yet evidence suggests the Chimú were able to maintain vast farms, producing more food than even those living in Peru today. To harness water for their agricultural pursuits, the Chimú built complex irrigation canals and aqueducts to bring water up from the surrounding valleys. These aqueducts sometimes spanned considerable distances, the longest covering over 50 miles.

“At the time, they rivaled the famous Roman aqueducts in terms of size and distance, and many are not only standing today, but still in use,” Prieto said.

To protect against seasonal flooding, the Chimú built the Muralla La Cumbre, an 8-foot-tall, 6-mile-long wall that stretched along two dried riverbeds. Prieto’s findings suggest that these usually dry ravines would flood during rainy seasons and threaten the farmlands along the western edge of the civilization, so the wall was erected to repel the excess water.

“We also found that there were large build-ups of sediments along the outside of the wall, and found those same sediments in layers of soil in their ancient farmlands,” Prieto said. “Our theory is that after the floods subsided, they collected these nutrient-rich sediments and used them as fertilizer for their farms.”

The Chimú were also astute in their crop selection, opting for varieties that required minimal water to grow. These included corn, beans, squash, and chile peppers, which continue to be staple crops in the region today.

From Meat to Myth

While the Chimú people boasted one of the largest civilizations in the region, they were not the first to settle those lands. Evidence suggests that there were people living there before the Chimú, albeit in a much smaller capacity. These people, who began living in the region about 3,200 years ago, are believed to be ancestors or precursors to the Chimú. Like their descendants, they appear to have had advanced technologies for their time.

Several sites belonging to those precursors have been found, and Prieto and his fellow excavators made another intriguing find in some of them: shark teeth. While the presence of coastal shark species was expected, what surprised the researchers were the teeth belonging to pelagic species, or sharks that roam open ocean waters, like the blue shark and even the great white shark.

“Finding the remains of these pelagic sharks has made us reconsider what we know about the naval capabilities of the Chimú predecessors,” Prieto explained. “In order to hunt these fish, they must have had sturdy boats and some form of advanced navigation, which is impressive considering these technologies were still in their early phases over in Europe.”

Prieto believes that there was an evolution of the cultural significance of sharks as their society developed. The earliest shark remains were found grouped together haphazardly in what were believed to be trash pits, but newer specimens were found in temples and tombs. This suggests that as millennia passed, sharks became less of a staple food and more of a class or religious symbol.

The Fury of El Niño

For all their technological advances and mastery of engineering, the Chimú people struggled with the same problem we face today: Try as we might to bend nature to our will, we can’t control the weather; we can merely shield ourselves from it. Despite constructing aqueducts to combat floods and redirect water, the Chimú were defenseless to the extreme weather events we continue to battle today.

El Niño, a cyclical weather phenomenon occurring in the Pacific every three to five years, afflicted the Chimú civilization. In some areas of the Pacific, like California, it causes prolonged dry seasons, but in Peru, it’s quite the opposite. Instead, El Niño brings heavy rainfall and wetter, cooler conditions, sometimes leading to floods and cataclysmic storms. In recent years, these events have become more and more extreme thanks to climate change, but historical records document several particularly severe El Niño events.

This posed a problem for the Chimú people, who turned to their faith in those times of crisis. They believed that their gods had sent the storm because they were angry, and they believed that they could appease their gods to calm the rain and wind.

“Most of their rituals and ceremonial events were related to sacralizing water and its sources,” Prieto explained. “They considered the mountains the keepers of water sources, although others believed the sea was the mother of all water sources.”

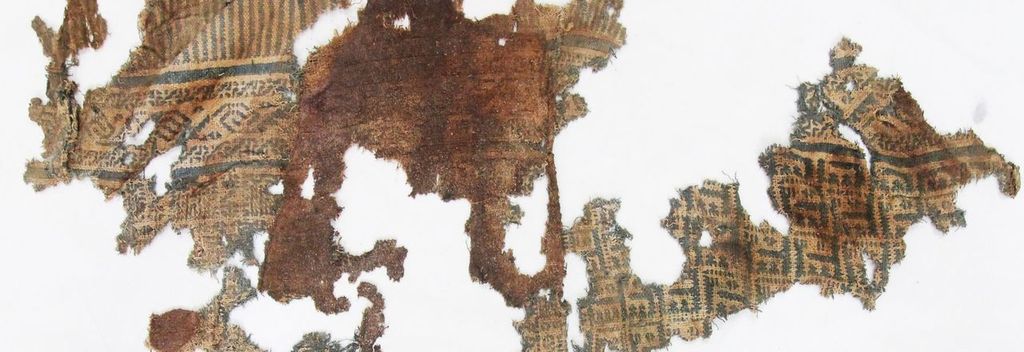

Their deification of the waters around them was also reflected in their art. Many woven textiles have been unearthed at Chimú sites, and the patterns woven into some of them seem to represent the spirals and waves of the ocean, while others appear to represent their canals and agriculture fields. “We believe these patterns emphasize the importance of water in their cosmovision system,” Prieto said.

Sacrificial rituals held profound significance in ancient South American religions, and the Chimú were no different. Prieto uncovered the aftermath of these sacrifices and many like them, finding mass burial sites in temples and coastal shrines throughout the littoral of the Moche Valley. At one such site near the Chimor capital of Chan Chan, excavators found the remains of 269 boys and girls, aged between 5 and 14, along with the bones of dozens of llamas curled alongside them.

Through radiocarbon analysis, the remains found at this site, named Huanchaquito-Las Llamas, underwent radiocarbon analysis, were dated back to approximately A.D. 1400. “Records suggest that there was a particularly bad El Niño season around this time, and we found layers of dried mud around the site, suggesting that these sacrifices took place in the rain,” Prieto explained. “Our working theory is that in order to calm the weather, the Chimú believed they had to sacrifice that which was most important to them: their children.”

The Chimú’s attempt to navigate the wrath of El Niño serves as a haunting reminder of our own vulnerability in the face of nature’s furies. As Prieto exposes more of their history, we are compelled to confront our own delicate balance between faith, sacrifice, and the fundamental drive to forge a path amid the relentless tempests of existence.