A science expedition to Greenland’s ice sheets takes center stage

Greenland, with its expansive ice sheets and remote wilderness, may seem worlds away. But this far-flung landscape harbors valuable insights into the future of life on Earth, making it relevant to each of us.

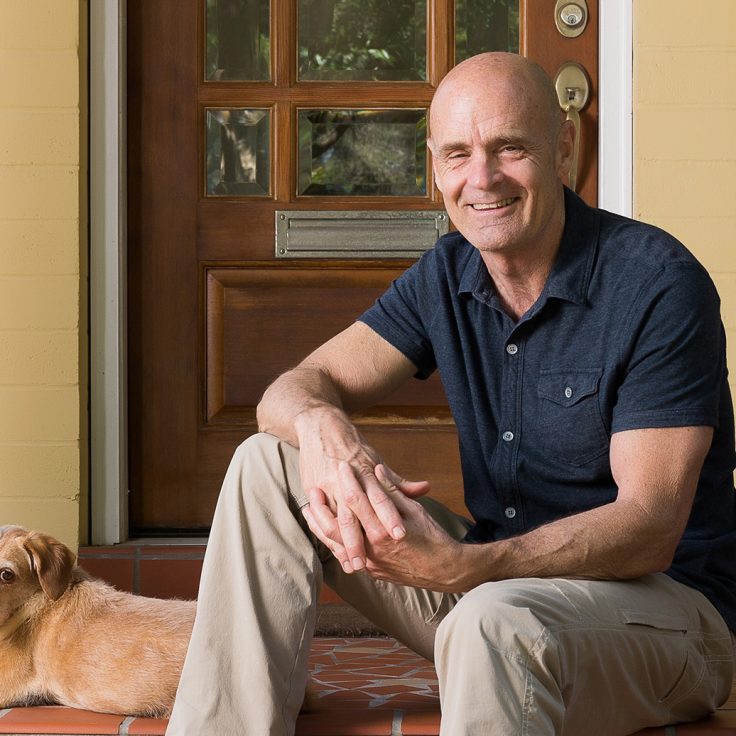

A new short documentary film, “The Baffin Bay Deglacial Experiment,” brings this distant world closer. Viewers venture aboard a massive United States Navy-owned research vessel, the R/V Neil Armstrong, to follow a team of interdisciplinary scientists, including University of Florida paleomagnetist and geological oceanographer ROB HATFIELD, during their monthlong expedition at sea.

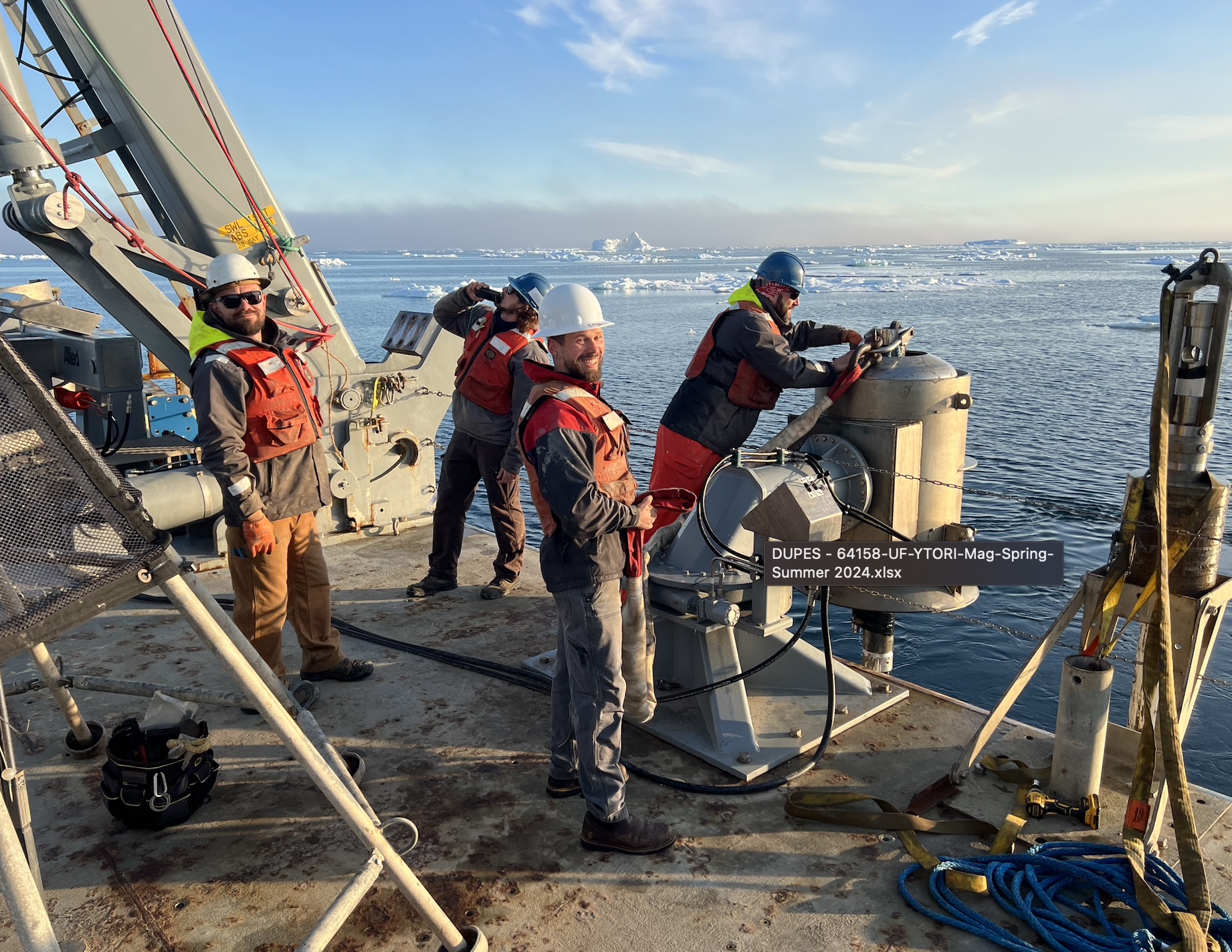

The film goes behind the scenes as the science party investigates the frigid depths of Baffin Bay, off the west coast of Greenland. Central to the icy expedition is an ambitious objective of retrieving ocean mud from depths of up to 5,000 feet of water. The mud holds a historical record of Earth’s last deglaciation period, around 17,000 years ago. During this period, the western margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet destabilized and rapidly retreated, but the reasons for this swift occurrence remain shrouded in mystery.

By analyzing the sediment composition and the geochemistry of animal shells within, the research team hopes to gain insights into the long-term interaction between the ocean and ice sheets, ultimately forming a broader view of the Earth’s system.

As chief scientist on the project, Hatfield works tirelessly to uncover the untold stories hidden within the seafloor, a complex and delicate task. The documentary provides a window into the team’s cutting-edge research, which involves using geophysics to image the seafloor and employing specialized tools to extract sediment samples with precision. It’s a taxing trip, but the scientists hope to help us answer pressing questions for our future: How fast did the ice melt? How quickly did the sea level change? Did the ice sheets disintegrate quickly or resist change? What does all of this say about our remaining ice sheets?

The film has garnered attention at global film festivals, winning “Climate Action Film” at the Arctic Film Festival in Svalbard. It has been selected for over half a dozen other science film festivals as of the date of this publication.

“I think films like this can help humanize scientific research,” Hatfield said. “Often, we hear about climate change through quantitative statistics, projections for decades out, or quotable sound bites. I think it’s important to show not only how work is done, but also the people doing it.”

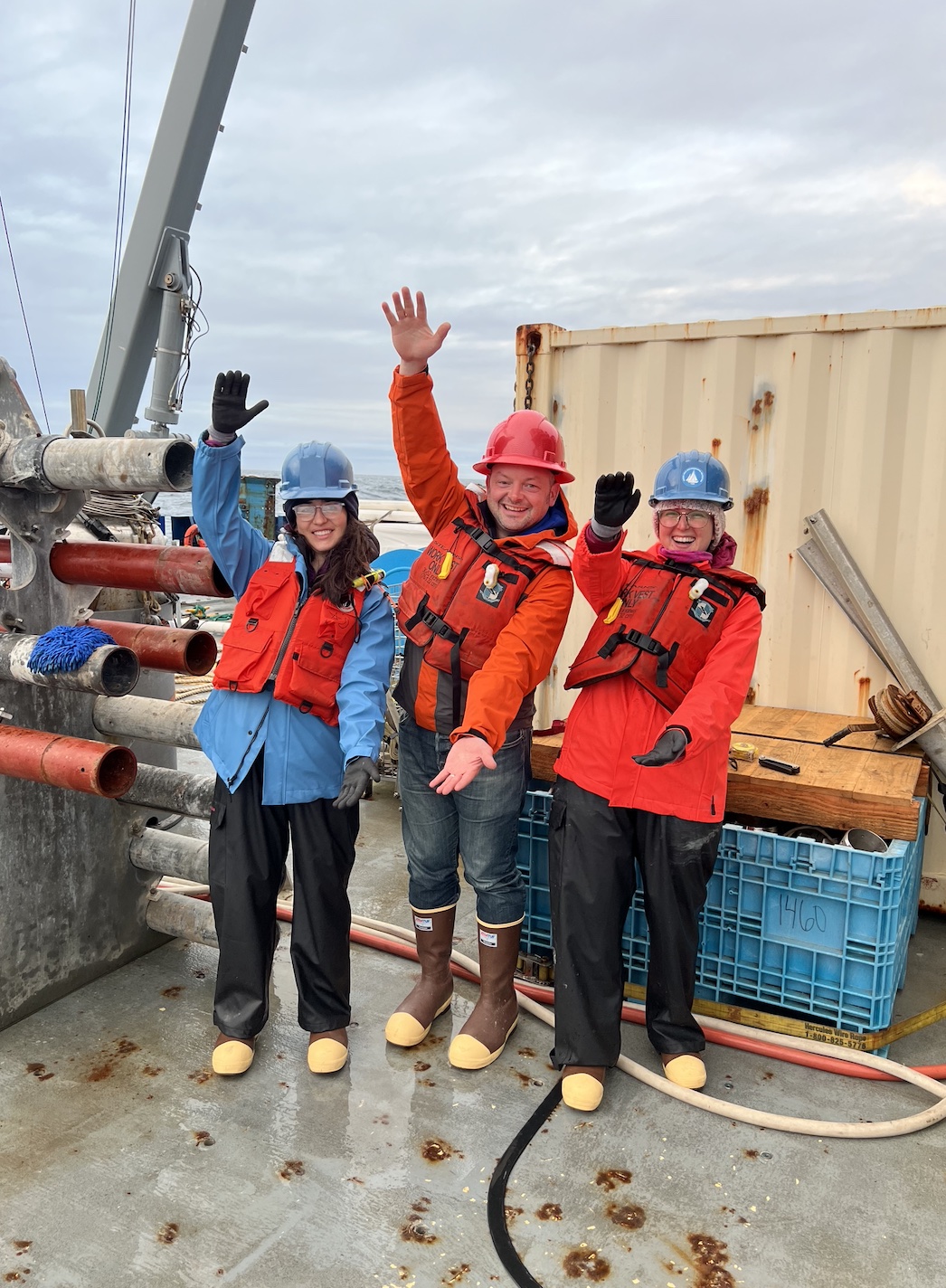

The science party was staffed with early-career researchers, bringing fresh perspectives to the work. Over half of the science party identified as female — a key aspect of this project, especially for a field that has historically excluded women, Hatfield emphasized.

The project, a collaboration between five institutions led by UF, included 21 scientists and 20 crew members working in 12-hour shifts over 33 days at sea. The researchers brought expertise spanning geophysics, paleoceanography, paleomagnetism, sedimentology, geochronology, and ice sheet history and behavior.

“The rewarding part of this work is being able to draw together a team of people with different specialties and address a big problem,” he said. “Not one person could answer the question alone.”

Hatfield brought along two of his doctoral students, PALOMA OLARTE and LINDSEY MONITO , but they weren’t the only Gators on board. Film director GEORG KOSZULINSKI (BA ’03, MA ’11) is a double graduate of UF’s film studies program, while co-principal investigator JOSEPH STONER (BS ’87, MS ’91), now a professor at Oregon State University, studied geology at UF.

While the voyage has concluded, its legacy endures through the film and the preservation of archived samples collected. Within the layers of sediment, a narrative emerges about climate change. Like tree rings, these samples can be dated, offering a glimpse into bygone days.

“How we archive these samples is almost as important as how we recover them,” Hatfield said.

Preservation efforts are crucial for scientists to reconstruct the planet’s climate history. Hatfield wants to know the implications of an entire ice sheet collapse and the ocean’s role in such a scenario. Each melt, crack, and break of the ice signals an urgency to persist in the arduous work of unraveling the secrets within these samples. The Greenland Ice Sheet, if completely melted, could cause a 24-foot sea level rise and trigger a series of catastrophic events. This has significant implications for billions of people worldwide, particularly those in coastal communities.

Recently, the science party reconvened to prioritize the research objectives they hope to accomplish in the next few years. They dedicated a week to extracting over 2,300 samples from the sediment cores obtained in Greenland. Hatfield hopes to use the samples to understand how ice sheets respond to a warming ocean.

“For impact, it is really important to look at the past to be able to contextualize future change,” he said.

The Baffin Bay Deglacial Experiment is a coproduction involving the BADEX Collaborative, Substream Films, and Lunar Kitchen Films. The BADEX Collaborative is led by chief scientist Rob Hatfield, and co-chief scientists Shannon Klotsko and Brendan Reilly. The project was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.