Samuel Proctor became the first UF Historian and Archivist when he was still a PhD student. He never left the role. Proctor was heavily involved with UF, so much so that rumor told he had four or five, maybe six, offices on the campus. Now, his name prefixes one of the nation’s largest oral history programs — in a field of inquiry that he helped pioneer.

Oral history involves the collection of stories about historical events or history in the making. Samuel Proctor ’41, MA’42, PhD’58 was deeply interested in the emerging field but observed that oral historians were interviewing politicians and other leaders. One problem with traditional historical inquiry is its tendency to rely on letters, newspapers, and other primary sources that favor the experiences and views of those in power. The methodology of oral history is crucial to getting the full story, but Proctor also thought that the “ordinary” people needed to be included.

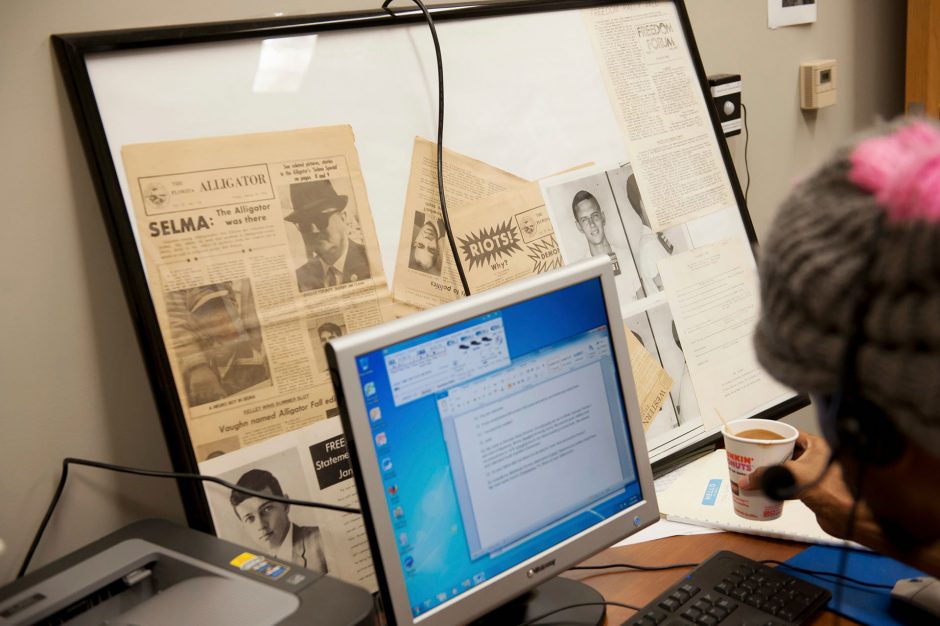

The Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP) at UF does just that. Proctor began by interviewing the first Jewish students at UF and, to this day, the program’s researchers talk to those who live at the cruces of sociopolitical change, especially those whose voices have been underrepresented in history. Their purview is marginalized and underrepresented groups, including veterans, the LGBTQ community, and civil rights activists. SPOHP researchers record and transcribe the interviews, which may last between five minutes and an hour, to produce comprehensive, immersive historical documents.

The Samuel Proctor Oral History Program not only teaches students how to interview and archive oral histories but also how to do scholarly research.

“There have been so many stories that have been missed throughout history. This is a great way to not miss them,” says project coordinator Brenda Stroud ’20.

“It takes a village to do good fieldwork,” says UF history professor Paul Ortiz, who has been the director for the last 10 years. Ortiz met Proctor once, decades ago, when visiting UF from Duke University. “I was this anonymous grad student trying to write my dissertation on African American history in Florida,” he says. “Sam didn’t know me from Adam, but when I walked into the Oral History Program, he just started talking to me. He gave me a whole afternoon. He was an incredibly generous man — a role model of what a professor should be.”

Proctor was actively involved with civil rights efforts at UF and in Gainesville. “In the mid-1960s, Sam was one of a small group of faculty members who signed a published statement in support of integration in Gainesville,” says Ortiz. “When you see Sam’s name, you realize what an example he set for the rest of them.”

“We interviewed a lot of the survivors of the 9/11 terror attacks. If I wanted the objective take on that, there’s a lot out there, but if I really want to know what it meant to those people, I have to talk to them.”

The Oral History Program continues Proctor’s legacy by using oral history methodology to expand an African American history of Florida — and beyond. In fall 2016, a group of researchers departed Gainesville for Mississippi with a packed itinerary that took them from Natchez to Sumner, each stop dedicated to a milestone in civil rights history. “I felt like I was there in the history,” says Stroud. The Mississippi Freedom Project has continued for the past two years and benefits from ongoing partnerships with community groups, says Ortiz. “We are the bridge builders. We don’t study, we learn,” he says.

“Every moment is part of the experience of learning,” says student assistant and history major Anupa Kotipoyina ’17, who transcribes interviews for the program. “A lot of people think transcription is boring, but there have been a lot of powerful interviews I’ve gotten to transcribe,” she says. One of her favorites was an interview with an activist reminiscing about Martin Luther King Jr.’s visit to her house in St. Augustine. “Imagine being the host to such a seminal figure in the civil rights movement in one of the few Floridian cities he visited.”

Listening to the researchers tell their stories about their story-collecting is ample evidence that history isn’t a stack of books and letters, but a living entity embedded in society, coded in bodies, and grown through language.

In 1921, Congress reluctantly unveiled a statue of suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott, then condemned it to the basement of the Capitol. Seventy-five years later, Joan Wages, who became the CEO of the National Women’s History Museum, was heavily involved in the campaign to return the statue to the Capitol’s Rotunda. The opposition remained, with even congresswomen calling the statue ugly and claiming it had no historical merit. Wages, who once had been denied a job when an interviewer told her she’d “just get pregnant,” was passionate about getting the suffragists represented in the Rotunda. The Woman Suffrage Statue Campaign was successful, and on Sept. 26, 1996, Congress passed a resolution to move the statue. More than 20 years later, Wages related this story to UF student Margaret Clarke ’18, who was visiting D.C. for the Women’s March on Washington as part of the Oral History Program’s new research project. “It was an amazing interview,” says Clarke.

Project coordinator Holland Hall contemplating women’s rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer at her gravesite.

The impetus to capture “history in the making” has driven several of the Oral History Program’s recent projects. The experiences of those present at milestone events and the reflections of observers upon those events are equally powerful data in oral history research. “Because we swim in that ocean of subjectivity, we can ask all kinds of questions,” says Ortiz. “We interviewed a lot of the survivors of the 9/11 terror attacks. If I wanted the objective take on that, there’s a lot out there, but if I really want to know what it meant to those people, I have to talk to them.”

Oral history enjoys a cross-pollination between the humanities and journalism. Says journalism student and SPOHP contributor Drea Cornejo ’17, “The oral history methodology introduced me to a different type of storytelling, pushing me to create projects with a more in-depth account of personal experiences and truly giving the stories the fullness they deserve.” Each project is a collaboration with the relevant department, center, or program in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences: the Women’s March and LGBTQ History projects with the Center for Gender, Sexualities, and Women’s Studies Research, the Mississippi Freedom Project with African American Studies, and, with the Bob Graham Center for Public Service, the 9/11 Project, which captured stories of people from around the world talking about that devastating day.

“The whole field is interdisciplinary,” says Ortiz. Because state funds cannot go toward student fieldwork, SPOHP’s research requires collaborations with other UF units to secure other funding. “And we’re into performance now!” says Ortiz. With the Center for Arts in Medicine, SPOHP researchers recently co-wrote and produced a play, Voices from the March, based on their experiences documenting the Women’s March and Inauguration Day in 2017. The play was performed at the Social Justice Summit presented by the College of Education in January 2018. “People contacted us after seeing it at the summit and commented on how important it was for their families and daughters to see it,” says Ortiz.

Many of the program’s efforts aim to popularize and decolonize history. By cultivating a living history, “we can bring history to kitchen table conversations across the globe,” says Stroud. To wit, the Oral History Program also conducts outreach through its podcast. Kotipoyina, who works on the podcast to share their research, considers it a valuable tool to help those unheard voices become heard. She intends to become a history teacher and bring oral history into the high school classroom.

The Samuel Proctor Oral History Program demonstrates how the transformative and productive potential of storytelling is crucial to a decolonized approach to history. SPOHP researchers document history as it’s being made and store the memories of those who witnessed significant events. By participating in this witnessing of memory, they create history themselves. In collecting the researchers’ accounts of their research in a method not dissimilar from theirs, their passion and personal revelations become clear, with adjectives such as “life-changing” and “amazing” peppering the conversation. Oral history has got them hooked. “I really like listening to people’s stories,” says Stroud. “Everyone has a story to tell.”