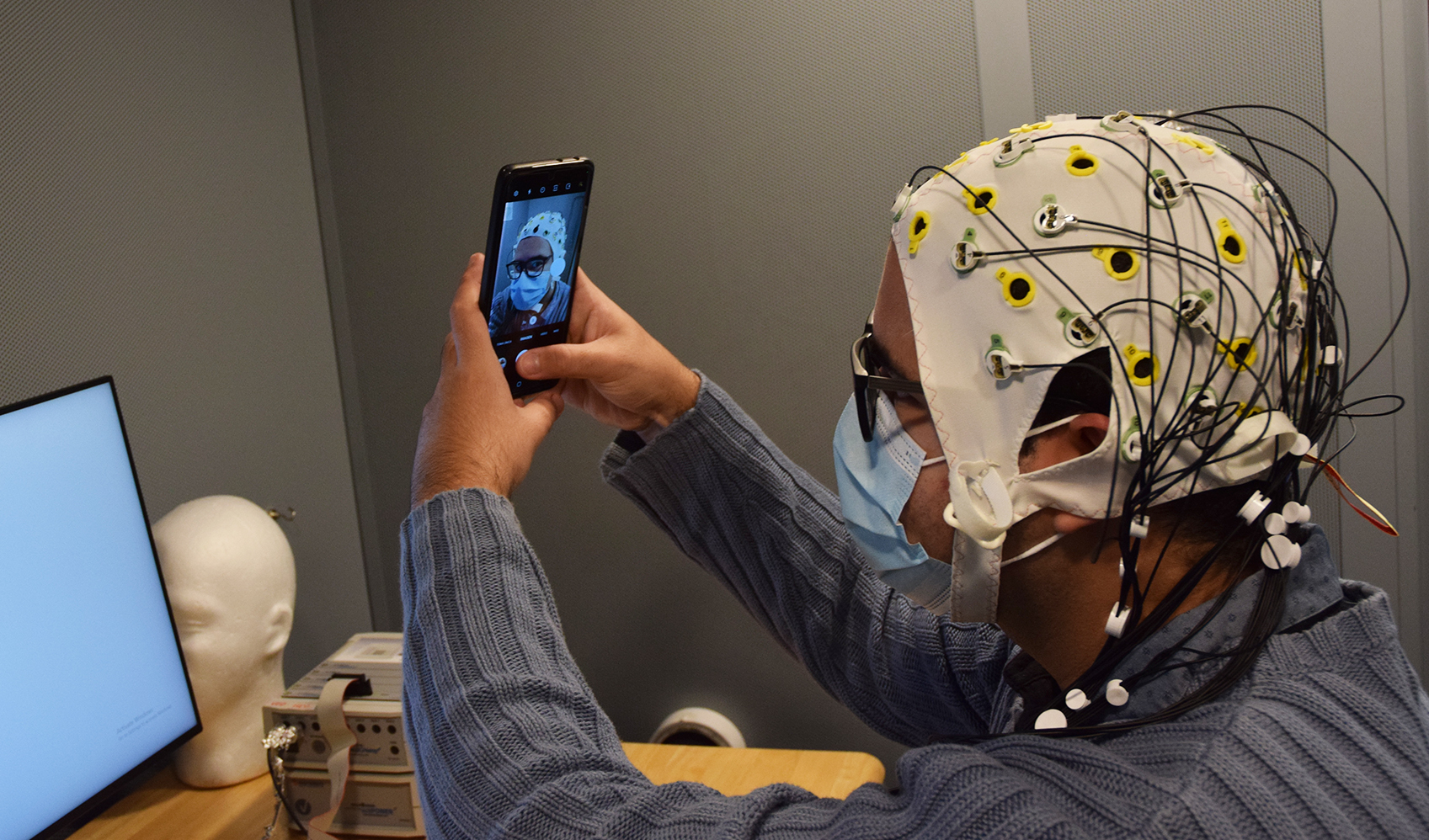

Reinaldo Cabrera Pérez takes a selfie while wearing an electroencephalography (EEG) cap. Photo by Michel Thomas.

A Team of UF Researchers Have Language on the Brain

Psycholinguists are revealing how the brain makes language possible – and expanding inclusivity in the process

The act of learning something new is among the experiences that define us as humans. The process releases the chemical dopamine into the brain, causing a rush of excitement that builds an emotional attachment between a person and what they’re learning. Rarely is this connection more powerful than when a child first begins to learn language.

Among the folds of offices in Turlington Hall is a small lab built to understand exactly that phenomenon. The Brain, Language, and Bilingualism Lab (BLaB) was founded by linguistics professors Eleonora Rossi and Edith Kaan in mid-2019 to address a daunting question: How does the brain make language possible?

For Rossi, interest in multilingualism came early. Growing up in a small town in Northern Italy, she learned to speak both Italian and German. By the age of 15, she had added English, French, Dutch and even some Latin to her repertoire.

Now, as an assistant professor of linguistics, she understands how complex the task of learning a multitude of languages is for the brain. And each person carries unique traits in their brain plasticity that affect the process.

Studying both monolingual and bilingual speakers, the BLaB’s team works to comprehend where these differences lie. Their research examines questions that include how age plays a role in language learning and how certain environments affect the brain’s understanding of a region’s dominant language. In the process, the researchers hope to counter the idea that people who speak multiple languages or speak certain languages are more mentally adept than others.

The human brain is always buzzing. Brain cells constantly communicate with one another by passing electrical impulses back and forth — even when we’re asleep. When research subjects come to BLaB, they answer a series of questions before making their way into a soundproof room. Here, they put on an electroencephalography (EEG) cap, a white swim cap dotted with green and yellow electrode openings.

The participants will then continue answering questions while their spontaneous electrical brain activity is being recorded in the neighboring room. The EEG cap captures the brain cells’ conversations and measures the electrical charges produced by the participant’s brain, translating them onto a screen of wavelengths. Researchers can analyze the signal and capture changes in the electrical activity, illustrating a participant’s grasp of certain concepts presented by the researchers. The EEG cap’s wires literally connect the subjects to the world of linguistics studies.

With the launch of BLaB, Rossi and Kaan aim to approach the field of psycholinguistics with inclusivity through voices on the team that expand social and cultural perspectives.

Undergraduate students Reinaldo Cabrera PÉREZ and Armaan Kalkat have worked together on the BLaB’s team to research how the brain interacts with a language in different contexts: for instance, the mental switch a bilingual speaker makes when interacting with different social groups. Kalkat, whose parents are from India and speak Hindi and Bengali, wanted to address the difference between heritage speakers and non-heritage speakers, exploring how their environments play a role in their brain’s engagement to their native language.

“A lot of times, heritage speakers lose their native language, and in America it becomes like English is dominant for everything,” said Kalkat, a linguistics and psychology major. He was drawn to linguistics to explore how a person could understand two languages but not speak either of them.

Cabrera Pérez, a linguistics and Russian studies major, joined Rossi’s team in 2021 to further his curiosity about his own relationship with the languages of Spanish and English. As someone who has struggled to come to terms with his identity as a bilingual speaker, he hopes his research can start a conversation about accepting other people’s different languages and comprehension.

“I think we have to make [our research] a bit more personal. I learned English when I was 16,” Cabrera Pérez said. “The work here really helps to destigmatize second-language acquisition, and just learning one [language] doesn’t make you any less proficient.”

Learn more about the Brain, Language, and Bilingualism Lab (BLaB) here.

This story appears in the spring 2022 issue of Ytori Magazine. Read more from the issue.