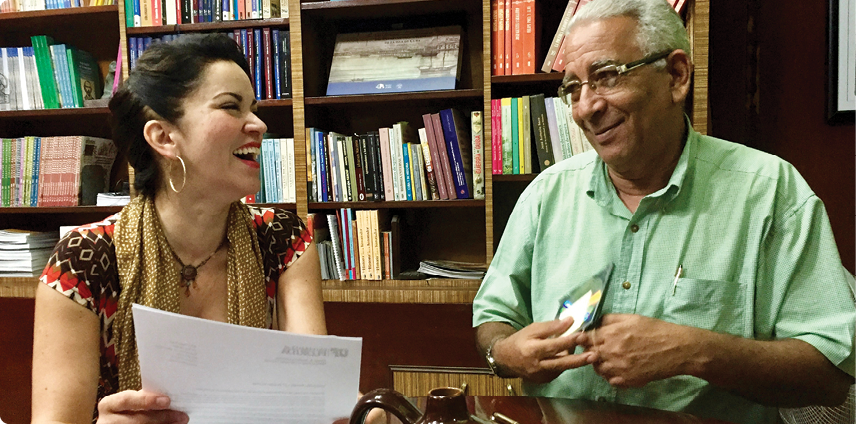

Photo courtesy of Lillian Guerra

A Groundbreaking Digital Archives Project Revives Cuba’s Past

UF historian unveils the day-to-day life of the island nation's people

Lillian Guerra never planned on climbing the branches of her family tree. Still, in the summer of 1995, she found herself biking through the streets of Havana armed with her mother’s address book referencing homes of family and friends. She showed up at their homes unannounced, knocking at their doors. Guerra’s immediate family left Cuba in 1964; no one had returned since. So it was quite a shock for relatives as they opened their doors to Guerra, who closely resembled her mother. Six family members even fainted upon seeing the unexpected specter from the past.

Guerra, now a professor of Cuban Studies in the Department of History, describes her Cuban heritage as “inescapable.” Growing up in the vast plains of Kansas, the closest person she could identify with was an African American boy in the first grade, one of her first friends. People would compare the turn of their noses and the color of their skin. Sometimes, derogatory terms were used to describe her father, which made Guerra want to figure out who she was and why her family was treated this way.

“I was plotting my path back to Cuba, even when I didn’t know it,” Guerra said.

Moving to Miami in 1984 proved to be a turning point for Guerra, as it sparked even more curiosity about her family’s heritage. She knew that to truly understand her past and Cuba’s kaleidoscopic culture and history, she had to experience it for herself one day. Over a decade later, Guerra finally found herself en route to the island nation, embarking on a mission that would give her a deeper appreciation for the complexities and contributions of Cuban society.

Starting with that fateful first visit to Cuba in the summer of 1995, Guerra spent many long days in sweltering conditions, gathering historical materials. Researchers were not allowed to take materials home or photocopy them, so Guerra painstakingly transcribed whole documents over the course of years. The resultant four books and dozens of articles and essays on Cuban history have expanded knowledge across the Straits of Florida.

Along the way, Guerra discovered the many realities of Cuba that separation from the island nation had previously denied her.

“When you have that experience, it just changes you,” Guerra said. “It became a mission to try to document this world for other people who would not be able to ever see it.”

Locals also began showing up with materials of their own. Often, they were strangers, just eager to share their archives with Guerra. As she collected stories and artifacts, Guerra recognized an urgent need.

“We really need a place in the United States that is sort of the premier location for knowledge of Cuba,” Guerra thought. “And not just knowledge that we put out through our books, classes, or an occasional interview in the press, but knowledge that can be accessed by anyone.”

So Guerra developed an open-access digital platform. From interviews

with experts on Cuban studies to visual evidence of daily life, Guerra’s digital archives take viewers on a journey through the country’s varied landscapes and diverse peoples.

“There is a lot of joy to be had in just learning from people,” she said.

Guerra is also interested in the preservation of Cuba’s cultural resources. As a shifting climate presents new challenges, many archives across Cuba are at risk of degradation. Governmental policies add an additional layer of strife. Thus, Guerra jumped at the chance to work with the Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba José Martí in Havana to digitize and consolidate resources between libraries in the United States and Cuba. These exchanges have placed the University of Florida at the epicenter of Cuba’s cultural resource conservation.

“I think a lot of our mission at the university should be to promote human universality — those things that make us connected to one another, regardless of where we are located,” Guerra said.

Guerra continues to pick up speed in establishing connections between Cuba and the University of Florida, encouraging students to continue her efforts. Two of her graduate students have received special permission to travel to the island for historical research this year.

“Together, we have seen the value, immediate impact, and legacy of doing at UF what nobody can do in Cuba: Make Cuba’s history a boundless field of knowledge, discussion, debate, inspiration and democratization,” she said.

Explore the archives here.