Dragging Language Textbooks into the Digital Age

Most textbooks are boring. Gillian Lord (opens in new tab), UF Spanish professor and chair of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese Studies (opens in new tab), is working to change that.

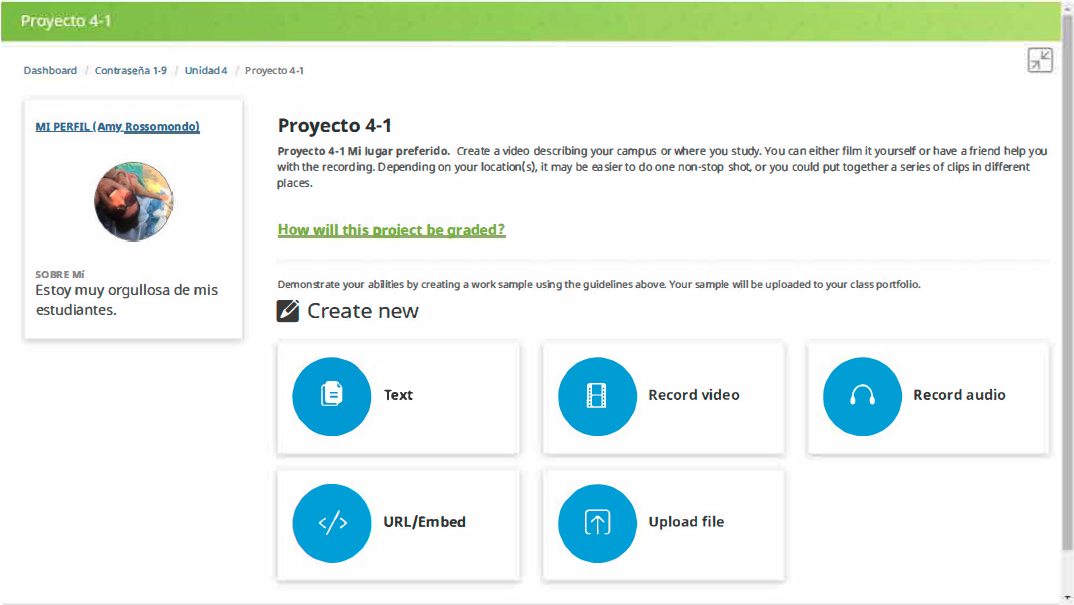

Lord and Amy Rossomondo, an associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Kansas, have developed an all-digital, low-cost Spanish language program called Contraseña (opens in new tab) (Spanish for “password”) that is bucking long-held norms for textbooks and language-learning curriculum.

Rather than simply adapting a printed textbook to a multimedia format, Lord and Rossomondo designed Contraseña from the ground up to embrace the digital age. Audio, video, text and other multimedia are seamlessly incorporated into the program’s instruction.

But its innovations go beyond the high-tech format: The curriculum also forgoes exams in favor of an emphasis on multimedia projects, in-class discussion and online interaction among students on a social network-like platform. Lord and Rossomondo believe the instruction will better resonate with students if they’re active participants rather than simply repeating back what they’ve memorized.

The new program builds on Lord’s past efforts to leverage technology to improve language instruction. Her online, open-access Spanish pronunciation program, Tal Como Suena (“How It Sounds”), launched in 2007 and has been used nationwide. To ensure its continued accessibility, she is currently updating Tal Como Suena with support from CLAS and the Office of the Provost.

Contraseña is already up and running at more than two dozen colleges and universities, with several more trying it out in the spring. UF has adopted it for online Spanish classes. Compared to more traditional classes, Contraseña students so far have had spent more time talking in class and are more confident about their language abilities while maintaining the same proficiency in assessments. Lord talked to us about how the program differs from what Spanish students are used to.

Q: What was the goal in developing Contraseña?

A: We all know the things we’re supposed to be doing in language classes, but the textbooks we have make it difficult to actually do that. They’re so traditional and boring and straightforward. That’s why after four years of high school Spanish you’re able to say things like “the dog is in the wastebasket” and nothing else. We need to do better.

I have long thought that we need to be taking better advantage of what technology offers us. Even in 2002, we didn’t need to have a paper textbook for phonetics anymore. I was proposing to publishers to use a CD-ROM because that was cool at the time, and they were afraid students and faculty weren’t ready for it. But I kept in touch with one of the publishers, and in fall of 2011, we met at a conference. I said, “I think the world may now be ready for a digital textbook,” and he was like, “That’s funny, that’s why I wanted to meet with you.”

Q: What did you want to do differently?

A: We wanted to focus on multimedia, by integrating audio, video, text — everything.

From the pedagogical side, we wanted to use a “backward” design. Instead of saying, “In chapter two, we have to teach past tense because that’s what everyone does in chapter two,” you say, “What do I want the learner to get out of this chapter?” If I want the learner to be able to talk about what they did last summer, then what would they need?

Instead of taking tests or quizzes, at the end of each unit the students have a little project. They’re creating with the language in a way that’s meaningful to them so they can showcase what they learned.

Q: What do you see as the advantages of those approaches?

A: The students have a greater sense of ownership and agency over their own learning, because it’s not memorizing what we told them to memorize — it’s using what they want to use.

We can’t teach every vocabulary word ever, so we’re going to teach some basics and how to use dictionaries well. It’s more content-driven than grammar-driven, so that in turn is more motivational and engaging.

Q: How do students use the material?

A: Each unit begins with a model. For example, we have a chapter on health and wellness that starts off by showing infographics. They learn commands, like “wash your hands,” and there is a segment on mental health that details signs of depression and anxiety. At the end of the unit, the students have to create their own infographic that they could hang in their student health center.

In another unit, students start by watching a series of videos of people introducing themselves — a student in a dorm meeting his roommate, a student meeting a professor and two students on campus. They then have to do an interview with a Spanish speaker for their final project. One group made a video based off of “Reservoir Dogs.” The effort they put into it was so heartwarming. Another group made one called “Spanfeld,” based on Seinfeld.

Q: Why do you think we need to bring these concepts into the digital age?

A: Everything else around us is digital, so there’s no reason why this shouldn’t be as well. But there are limits to that. It’s not cool to have your Spanish professor following your Facebook posts. We wanted to capitalize on the fact that students live in a digital world — but not invade their digital world.

For the project in each unit, they share it on a social network page and comment on each other’s. They actually develop a better sense of community than they do in other classes.

Q: Prior to developing Contraseña, you created an online multimedia Spanish pronunciation program called Tal Como Suena. How can technology help students master pronunciation?

A: Imagine reading a description of a sound in a foreign language, with examples of words containing that sound, and even a drawing of what your tongue and your mouth should look like as you pronounce that sound… Now, imagine yourself listening to that sound and the words containing it, while watching a native speaker pronounce it, and interacting with a step-by-step animated diagram that shows you how your tongue, your lips and your teeth are moving and interacting in the process of making that sound. Which do you think would be easier to understand, and to imitate?

My goal with creating the Tal Como Suena modules was to provide Spanish learners with a place to learn the important aspects of Spanish pronunciation, on their own time and at their own pace, and to practice and get to feel comfortable with it. Technology makes both of those things possible.

Q: Some educators might be wary of the fact that Contraseña that doesn’t include exams. Why do you think it’s for the best?

A: We actually had to write a test bank because some people won’t adopt a program unless there are tests. But the idea is performance-based assessment. We want it to be personalized enough for the student to feel like they’re contributing something as opposed to memorizing and regurgitating.

The truth is, after two semesters of Spanish, 10 years later they’re probably not going to remember much of the detailed grammar and vocabulary words — so why not make it something that can at least resonate with their lives?

Interview was condensed and edited for clarity.