How Comics of the Congo Came to the Libraries of UF

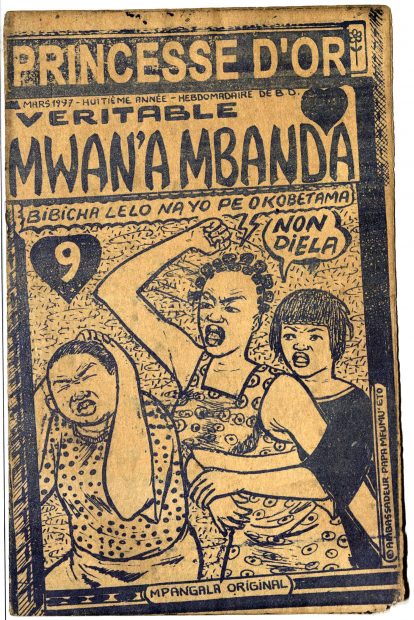

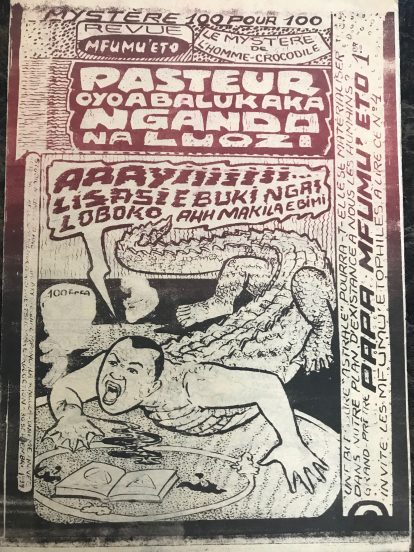

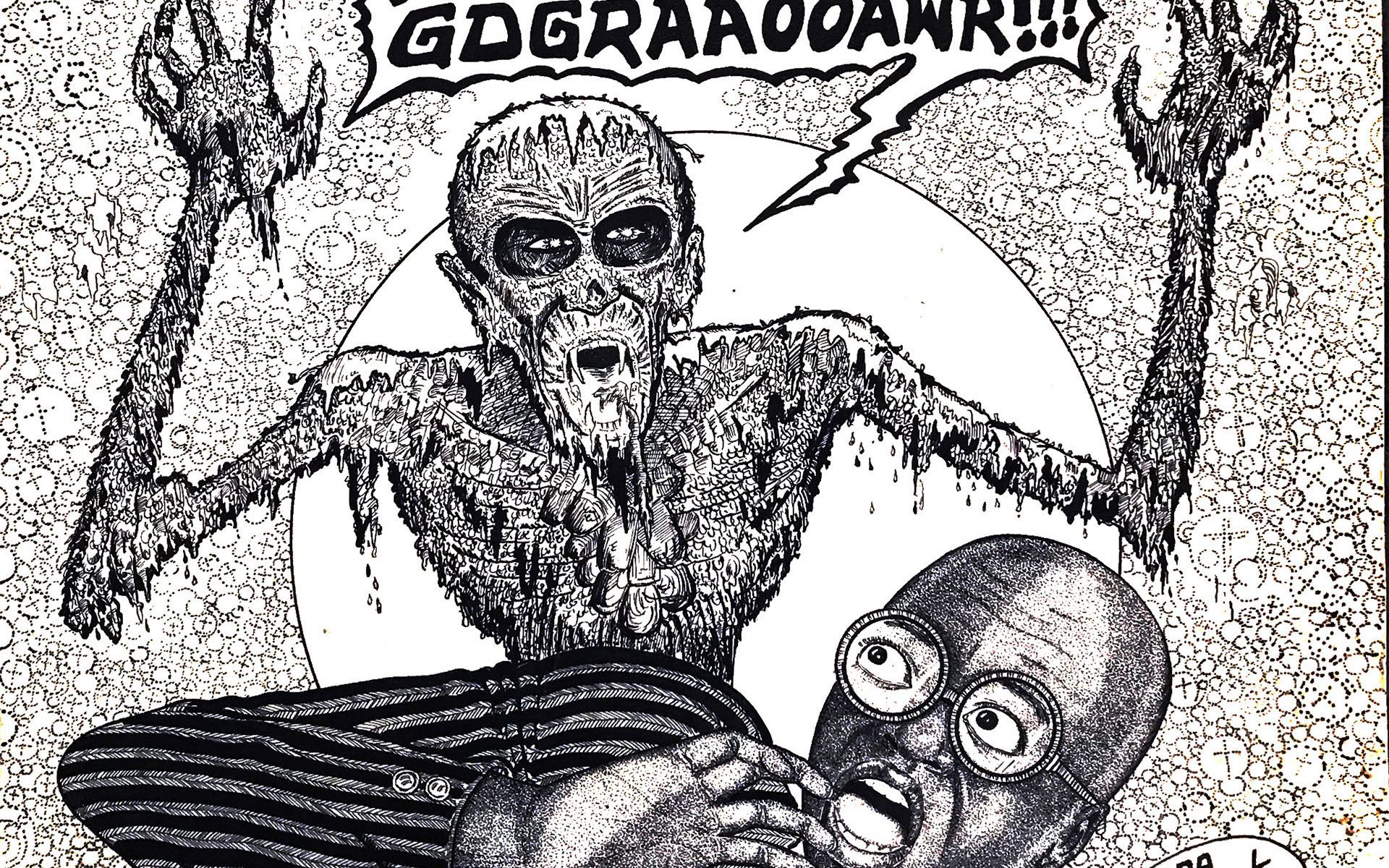

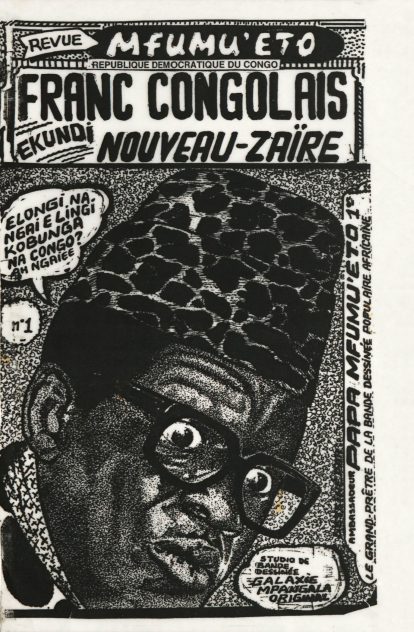

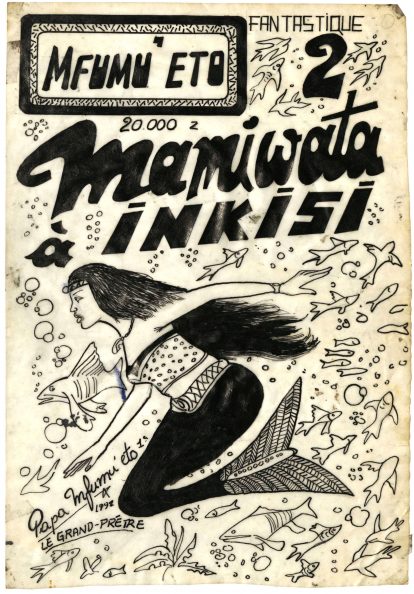

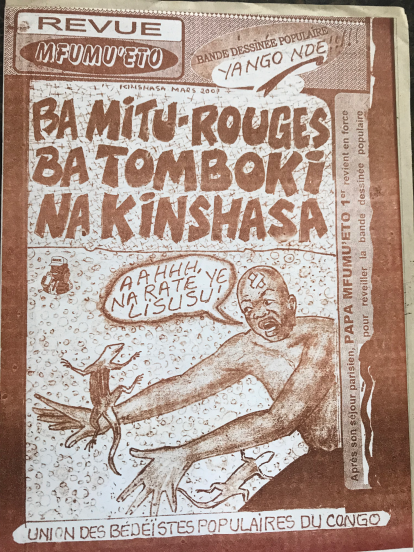

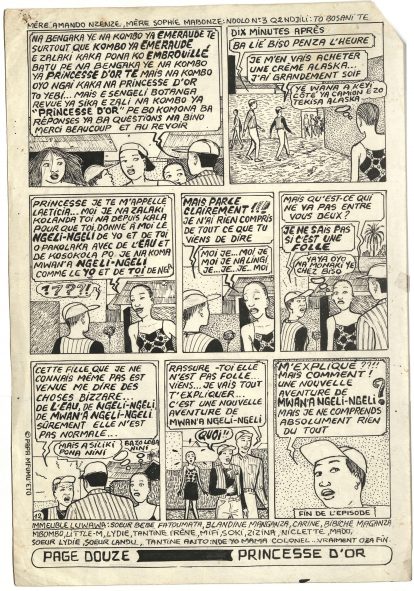

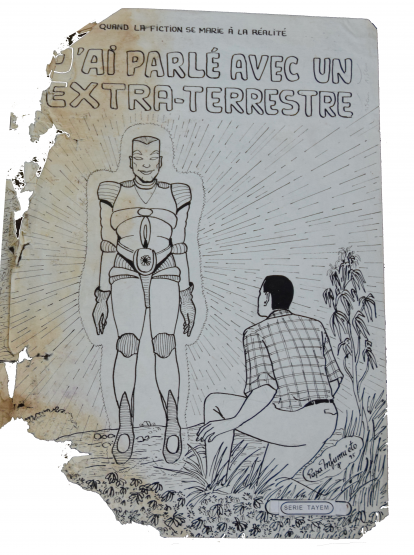

In a locked room at Smathers Library on the UF campus, rows of manila folders and stacks of cardboard boxes are filled with polyester sleeves and simple copy paper, among which hide one of Smathers’ — and the world’s — most unique collections. The work of Papa Mfumu’eto, a comic artist and illustrator from Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, encompasses thousands of comic books, zines, and advertisements that tackle democratization, gender roles and sociopolitical change, and Congolese mythology and spirituality.

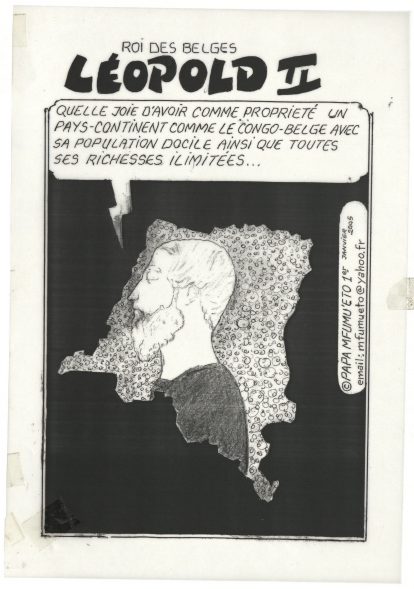

Nancy Rose Hunt, professor of African history, usually focuses on medical and gender issues in Africa, but a request from a Yale colleague to study the sociocultural impact of Tintin au Congo in then-Zaire piqued her interest in comics produced in this central African country, formerly the Belgian Congo. After collaborating on an enormous archive of comics from the 1920s through the ’80s, Hunt discovered Papa Mfumu’eto, one of the most prolific and admired comic artists of the “zine era” running from the late 1970s into the mid-1990s. In 2001, while in Kinshasa for other research, Hunt decided to meet the larger-than-life artist, whose self-portraits permeate the collection. “When I arrived at his door, it was a very affluent period for him. He’d just come off some nice contracts,” she says, remembering his fancy stuffed chairs and couch. (The artist frequently does commission work for advertisements, many of which blend in motifs and recurring characters from his comics, beloved by Kinshasans.) “His work was coming off the ceiling and under the chairs, just everywhere. I have a background as an archivist before I became a historian, so my instincts were to preserve it and conserve it,” she recalls. “He’d never heard the word ‘archive’ before, but he was happy to hear it.” Hunt persuaded him to entrust the collection to her. It was crucial to find a secure home for what she calls a “gold mine” for any Africanist.

Getting the archive to America was not a seamless endeavor. However, more than 15 years later, Hunt is pleased with the outcome, as is Smathers’ African Studies curator, Daniel Reboussin. “I wasn’t sure it would all happen as easily and beautifully as it did,” Hunt says. She returned to Kinshasa in 2007 to read some of the comics with Papa Mfumu’eto, while working on her Lingala, the language in which the bulk of the text is written. Hunt knew she wanted a repository for the collection in the United States or Europe, although some warned her that no American institution would be interested, because this kind of comic art was better known in Europe. Pitching and moving the collection would be risky. Hunt focused her scouting in France and Belgium during 2014 and 2015 when she had a research year in Paris. To her delight, Paris’ Fondation Cartier included examples from the archive in a 2015 exhibit on Congolese art; this inclusion thrilled both Hunt and Papa Mfumu’eto, who produced an essay and several interviews, respectively, that signal-boosted the collection. Intrigued, Paris’ Quai Branly Museum made a bid for the collection to be stored and exhibited there.

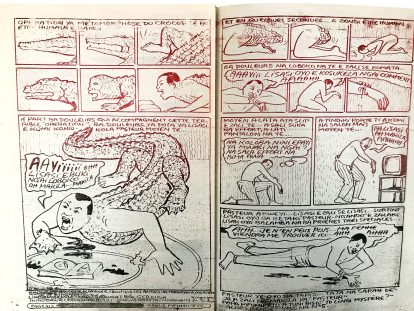

Zombies, mermaids, and more appear throughout the collection, as do creatures of superstition such as chameleons.

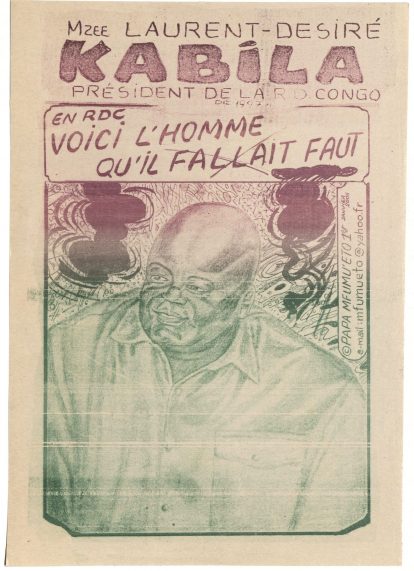

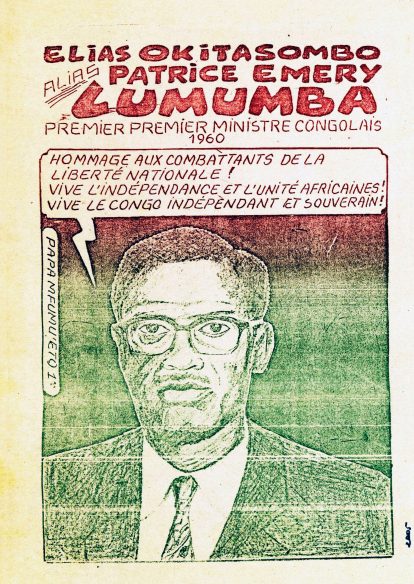

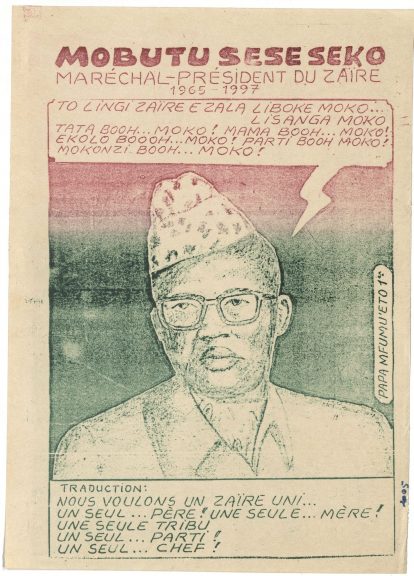

Yet in the end, Gainesville seemed to be the pre-destined home of the Papa Mfumu’eto archive. The University of Florida was recruiting Hunt, who also struck up a friendship with Reboussin, to whom archiving the work was especially important. Many of the comics were created during the period of transition from the Mobutu regime to democracy. “It was a time where people weren’t free to speak about politics, about opposition,” he says. “Some of [the comics’] themes might not be overt political speech, but are referring to political conditions.” He and his team have spent close to 100 hours processing the archive and expect many more to go, with an anticipated completion date in 2019 or 2020. This dedication is aimed to protect and preserve for posterity. “We should make sure that things are available to scholars a hundred or more years later. I’m sure that 100 years from now, people will be interested in that transition point in Congolese history.”

The collection stayed in Paris in a safety-deposit box for about 18 months while Hunt discussed possible homes for it with Parisian curators. Yet Smathers Library, along with the Harn Museum of Art’s history of curating Congolese art with Belgian institutions, the Center for African Studies, and the local comics school, the Sequential Artists Workshop, collectively whispered to the appropriateness of a Gainesville home, and Hunt, listening with intrigue, accepted the job offer from UF. Finally, the time had come to bring the collection to Gainesville. Hunt and Amy Vigilante of University Galleries personally traveled to Paris to retrieve the collection, puzzling on the flight how to best wrap them. The return journey was successful, and Hunt and Reboussin opened the packages on March 9, 2017, at a small round table in the locked room at Library East. Now, Reboussin and the Smathers archival team are carefully processing the pages, some of which are original paintings and sketches, some of which are printed on paper that time has reduced to mere wisps. There was very little organization to the collection when it first arrived; due to the many fragments and condition of the materials and without a familiarity with the sequential art form, archivists met new challenges in processing the collection.

Thankfully, Hunt had pinpointed the Sequential Artists Workshop while eyeing Gainesville, and its founder, Tom Hart, was happy to come on board the project. When he’s not using the comics for public outreach on campus and in local schools — “Tom is a beautiful ambassador for African studies,” says Hunt — he’s using his expertise in comic layout, illustration, and production to help the archivists know how to process the collection.

“We don’t have but maybe a dozen complete comic books,” says Reboussin. Hart is able to match pages that were likely in the same spread and extrapolate from the layout off cells how large the complete comic book would have been. “He knows immediately if it was a 16-, 12-, or 8-page comic book. He sees how the text and the image fit together physically within the cells. It’s a different level of insight than someone who’s looking at the imagery itself or other themes in Congolese society. It was wonderful to have these conversations.”

The conversations continued at the 2018 Gwendolen M. Carter Conference hosted by the Center for African Studies. Hunt co-organized the conference with Alioune Sow, professor of French and African studies at UF; the Sequential Artists Workshop remained deeply involved, and the creative dialogue between image and text expanded into special appearances by Congolese novelist Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Australian writer David Carlin, and Didier Viodé, a performing artist from Benin. Through connections made at the conference, Hunt and Reboussin anticipate further exhibition of the archive, notably a Belgian museum in Ostend in 2020.

Papa Mfumu’eto is unique in that he produced comics for so long using a non-colonial language, says Hunt, and she hopes to introduce Lingala studies to UF. Reboussin too sees a world of possibility in the collection. “It’s just great working with a diverse group of people,” he says. “Everyone sees something different, especially in a collection that’s really rich. The more you look, it just gets deeper and deeper.”

“There is a very strong religious imagination inside this archive, full of things about the relationship between the visible world and the invisible world — the visible world being the concrete material world that we live in, the invisible world being a world of spirits and witches and ghosts, and also the relationship between the living and the world of the dead. Many American students are kinda shocked at first sight, because there are a lot of strange beings that are floating through it, images of cemeteries and graves. There’s something a little spooky about this collection.” — Nancy Rose Hunt

Political leaders such as the infamous dictator Mobutu Sese Seko; the independent Democratic Republic of the Congo’s first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba; the unpopular president Laurent-Désiré Kabila; and King Leopold II of DRC’s Belgian-colonial past appear frequently in Papa Mfumu’eto’s work.

“There is a lot of stuff about domestic struggles between female rivals, i.e. co-wives or co-lovers in the same household. Some of these intimate themes burst out into things that are more metaphorically political, e.g. a man who turns into a snake, devours a sexy woman, and then turns that sexy woman into dollar bills. As soon as that image appeared on the Kinshasa streets, people understand he was talking about Mobutu.” — Nancy Rose Hunt