Fieldwork is Crucial to Geology. A New Course Ensures All Can Take Part

The GEOSpace Project, led by UF geologists, makes fieldwork accessible to everyone

Last summer, University of Florida geologist Anita Marshall traveled to Northern Arizona to scout locations for a field course she would be leading in 2022. Many of the questions she aimed to answer on her trip, however, did not concern the rocks, volcanoes and sedimentary features the students would study. Instead, Marshall was making sure students of all abilities could access the chosen locations. Driving from site to site in a wheelchair-accessible van, she had a long list of considerations to keep in mind. One example: How far away is a flush toilet?

“That’s a really big concern for accessibility that people often overlook. It doesn’t matter how cool a site is — there has to be at least a gas station with an accessible stall within a reasonable drive,” said Marshall, a lecturer in the Department of Geological Sciences.

No comprehensive resource exists to answer these questions, underscoring the urgent need that will be addressed by the GEOSpace Project. The new course was designed by Marshall and fellow UF geologists Stephen M. Elardo and Amy J. Williams, with collaborators at Central Connecticut State University and Arizona State University.

Supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation, GEOSpace provides a fully accessible and inclusive opportunity to take part in fieldwork, a key component of a geological sciences education. Firsthand experiences studying real-world geological features are an early chance for students to see themselves as practitioners — but the work often takes place in remote locations, limiting the participation of students with disabilities or other considerations that impede their travel. Students’ eagerness for a solution was clear: 70 students applied for the 12 spots available in the first-ever run of GEOSpace.

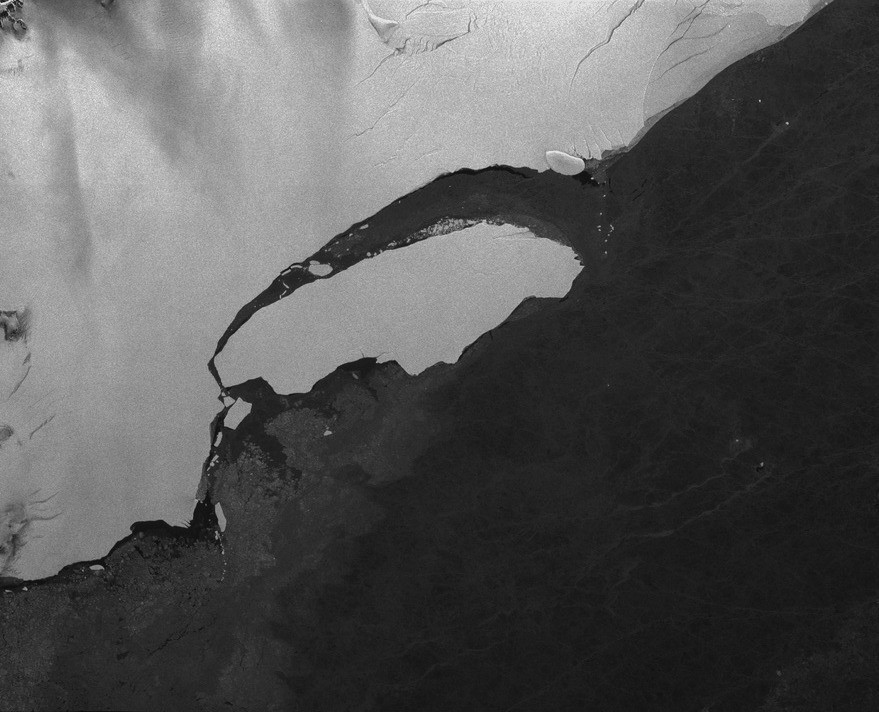

The new course, which launched this May at the Grand Canyon, Sedona and other Arizona locales, breaks down this barrier through a number of avenues. Some of the sites are in extreme locations that can’t be reached on foot by anyone, making them equally accessible to all participants by drones and other remote technologies. Lidar (light detection and ranging) scans will allow students to create 3D models of sites that can be examined by all participants. In other cases, they’ll use iPads and GoPro cameras for real-time data sharing and livestreaming.

Along with the on-the-ground accommodations, the course will use portable Wi-Fi hotspots so students can take part from anywhere. The fully virtual option prompted skepticism from some corners when the GEOSpace team first proposed it in 2019, but it became more broadly palatable after the COVID-19 pandemic forced millions into remote work.

“We cannot call this an accessible field course if we don’t offer a virtual option. Full stop,” Marshall said. “There are so many reasons why people can’t disappear into the wilderness for weeks at a stretch. And we, as a discipline, don’t like to acknowledge that.”

The virtual option is a big deal for Michelle Cabalceta, a student majoring in geology who transferred to UF in the fall. It will allow her to study the volcanic fields that fascinate her without leaving behind her toddler or neglecting a busy work schedule.

“Most programs are on-site, and the availability is usually limited and very competitive,” Cabalceta said. “The GEOSpace virtual option gives me the opportunity to join the team virtually and network as well.”

When Sidney Washburn, another UF geology major, went on fieldwork excursions in the past, she was struck by the physical and mental demands as she managed a disability and other challenges.

“There have been many times personally where I have been worried about keeping up out in the field,” Washburn said, “but the group of students, faculty and mentors I have met so far for this project has given me great reassurance and comfort.”

For Marshall, who was inspired to design GEOSpace in part because of a physical disability of her own, the first fully accessible field course is a new frontier as worthy of exploration as an uncharted volcanic field.

“We’re figuring this out as we go,” she said.

This story appears in the spring 2022 issue of Ytori Magazine. Read more from the issue.