Photo by Suzie Israel.

Getting the Dirt on Space Plants

How geochemist Stephen M. Elardo helped grow plants in the Moon’s soil for the first time

University of Florida scientists made a giant leap this year by becoming the first to grow plants in soil from the Moon. Their discovery presents new questions that seem endless: Could lunar farms one day exist? How can plants adapt to a lunar environment? And what impacts would the plant have, in turn, on the Moon’s soil?

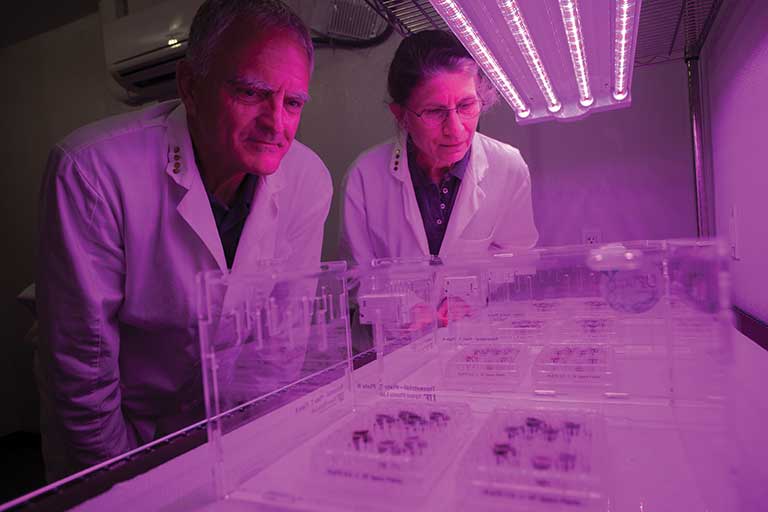

Long before any of those exciting possibilities could even be considered, the researchers had to get the right soil for the job. That’s where STEPHEN M. ELARDO came in. An assistant professor of planetary geochemistry and experimental petrology in the Department of Geological Sciences, Elardo offered insight into how the special characteristics of lunar soil could impact plant growth.

Led by Robert Perl and Anna-Lisa Paul of the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Science, the team obtained soil from NASA collected decades earlier, during the Apollo 11, 12 and 17 missions. The samples, known as lunar regolith, presented a number of challenges. First, they were only 12 grams in total, or a few teaspoons. What’s more, the regolith was on loan and would need to be returned.

Through creative problem-solving, Ferl, Paul and Elardo were able to find inventive solutions and make several major discoveries. They learned that the maturity of lunar soil played a role in plant growth and that the soil did not disrupt the hormones and signals involved in plant germination. Elardo now turns his attention to the question of whether the soil will become more hospitable to the plants with the addition of water and nutrients.

With this new pursuit on the horizon, Elardo shared his contributions to the stellar discovery and what comes next in their future explorations.

When you first heard about the experiment, what was your initial reaction?

My initial reaction was honestly, “That’s never going to work. They’re not going to grow.” So obviously, the results of the experiments were a surprise to me. For me, this was a whole new way to think about the Moon. I’ve been looking at the Moon from the perspective of a geologist. Now I’m looking at it from a more of an exploration standpoint — and thinking about plants, which I admittedly know very little about. That was a little daunting, but also really exciting.

What did you see as the purpose of this experiment?

This for me was very much a proof of concept. Is this even possible? Will the plant die and shrivel up and be of no use to anyone? Turns out it did grow. And from there, that opens up a whole array of other questions: What other changes can we make to lunar soil to make plants grow better? Are there different lunar soils that are better or worse for growing plants?

What stresses on the plants and changes in the soil did you find?

Plants didn’t evolve to grow in materials like that. So, it’s expected that they’re not going to perform to the best of their ability in the soil. To get a plant to grow, you have to add things to the soil. You had the plant itself, obviously. Rob and Anna-Lisa added a nutrient solution to the soil, and added water — we don’t really have liquid water on the Moon. Those are things that were not present on the Moon when soils are formed, and they’re naturally going to affect the composition of the soil itself.

What will your contributions be moving forward?

We’re going to be looking at the soils after the first round of plant growth. How did the mineralogy change? Did you see things like oxidation of iron? I’m going to be characterizing the soil after each plant growth step to understand how the minerals in it are changing.

Do you have any predictions?

I would be surprised if the soils don’t get more hospitable to plants. I think adding water is going to have a positive biologic impact on the soils, and oxidized iron metal could make it more amenable to plant growth. I suspect the plants will grow a little bit better over the next couple of growth cycles.

Were the results of this experiment a stepping stone for sustainable agriculture outside of Earth?

It’s hard for me to look that far in the future. I see this potentially being the first step in a very, very long chain of steps. I think if humans are ever to the point of growing plants to use for food on the Moon, or Mars, it could be hundreds of years from now. This study could turn out to be one of those first steps that were taken.

Interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

This story appears in the fall 2022 issue of Ytori magazine. Read more from the issue.