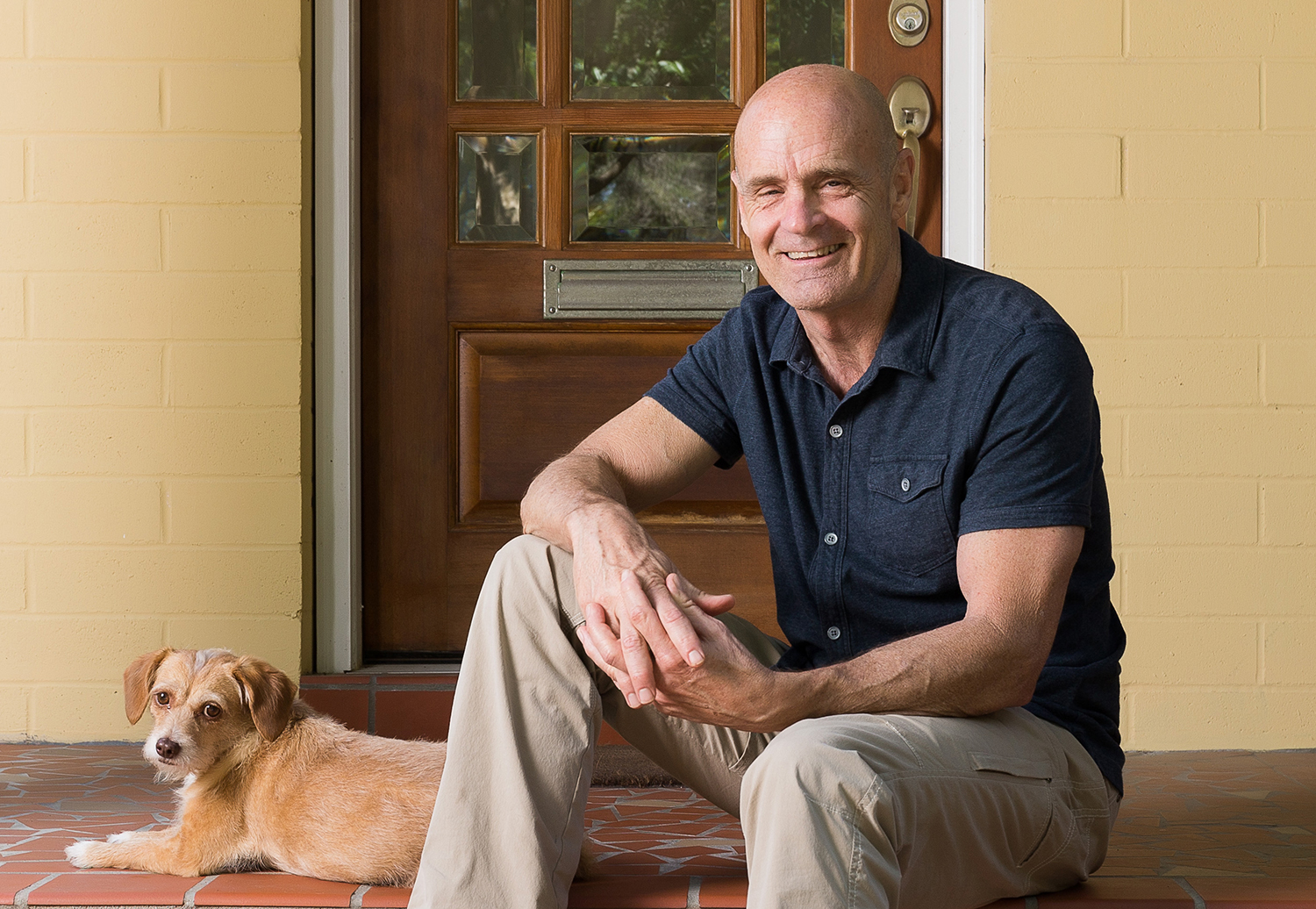

Jack E. Davis

Jack Davis: Growing up on Santa Rosa Sound

Lulu had a water-dog’s itch and had it bad. From one day to the next, she fished the shallows fronting our house nonstop. Back and forth she sloshed, pouncing on anything darting or flashing, her cropped tail spinning like a boat propeller. She was the family’s dog, a springer spaniel with sun-faded liver-and-white coloring, but I had a similar itch that gave us a special bond.

We forged it after my family moved to Florida when I was 10. Our new house was a proud old one. A man named Darling built it of southern pine between live oaks beside Santa Rosa Sound, a 40-mile-long luminous sliver that underscored Florida’s western panhandle. Our view across took in an equally rangy barrier island quietly left undeveloped and preserved in a dune-quilted serenity. At night, lying in bed beside a breeze-filled window, you could hear breakers rolling onto its beach from the Gulf of Mexico. The immutable sea was the animating center of this canvas-like setting. But it was the Sound that situated my days.

At first, they felt lonely. I had known only suburban enclaves booming with kids, and our new home came with neither bicycled streets nor playmates. But I had the Sound, and soon enough a canoe with a six-horse kicker clamped to its squared-off stern. I provisioned my vessel with a fishing rod, live bait, and cream-filled Mickey cakes (Merita Breads’ not the Mouse’s).

With Lulu in the bow sniffing and tasting the salt and tides, we explored every spoil island, lagoon, and hideaway. We hurdled the wakes of sturdy tugs pushing rusty barges, and bored through afternoon rainstorms that washed the day clean before the sun reappeared and steamed the wetness out of us. I cast my fishing line singing toward dark shapes in the water, hoping to land a big one. Lulu pored over flats for anything of any size. Her catch rate was zero but her joy was off the charts.

At day’s end, when I smelled like, well, a wet dog in from the flats, I jumped off our dock with a bar of soap. Lulu trolled the home shoreline for a last chance with luck, her spinning tail anticipating.

“Some say water is not a living thing. But the Sound taught me otherwise. It lives within me.”

At my grade school, they didn’t teach about water, nature, and the like. I don’t think I heard the word ecology until college. But that didn’t matter. Each vibrant season on the Sound was a semester of learning.

In the fall, great mullet runs set out for spawning grounds in the Gulf, with feeding dolphins hot on mullet tails. Slack tides of winter opened bountiful flats to northern plovers, Sanderlings, and dunlins. Once plump with migration fat, they answered spring’s call to return to upper latitudes. Wild millions of feathered others winged in from as far away as Patagonia en route to as far north as Arctic breeding grounds. In summer, crabs, minnows, baby shrimp, and mysteries of all sorts hid in shaggy seagrass beds eluding predators. After outgrowing their sanctuaries, hapless numbers ended up in the gullets of pelicans and the talons of osprey.

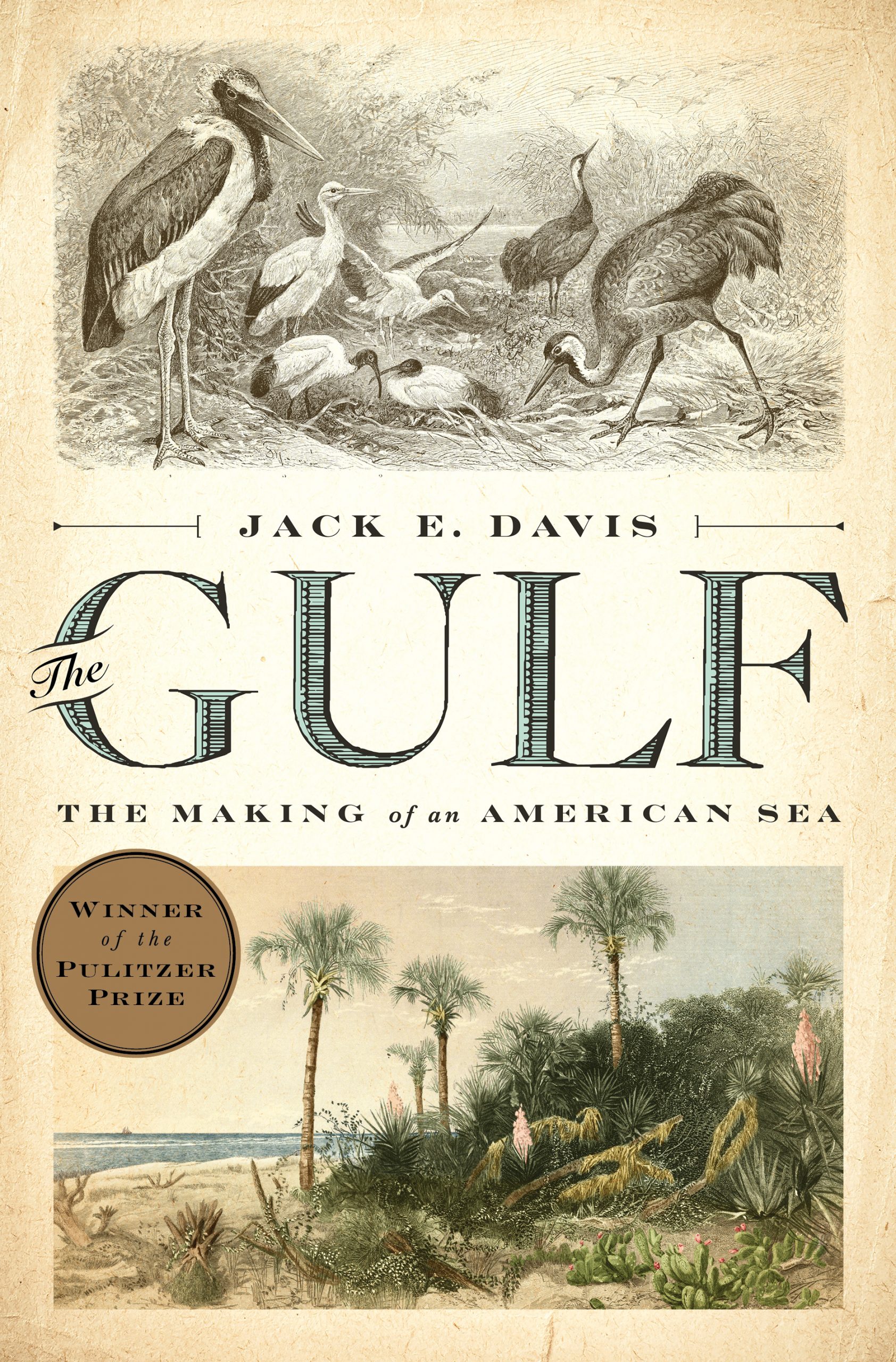

Long after Lulu departed this world to fish in another, I found myself writing a book about the Gulf. The inspiration had come like a calling yet seemingly out of nowhere. All the while, my thoughts kept drifting to the Sound, many years and many miles removed. So, on one fine spring weekend, I returned.

Happily, little had changed. The starkest departure from my past was me paddling a kayak with my 11-year-old daughter holding forth at the bow. As we passed over remembered waters, it struck me that my boyhood attachment to the Sound had endured and gently nudged me to write about its parent sea.

New research at the time revealed that humans are endowed with neurological and psychological stimuli that call us to be near water. In motion or stillness, it is transporting and vitalizing, inviting happiness and inner peace. Just as we inhabit watery places, water inhabits us.

None of this came as a surprise to me. It affirmed what had arisen within, the sea stirring me to write not solely from the mind but from a deeper place, to connect with readers as the Sound connected with me so that they might know the Gulf in its truest nature — essential to our quality of life.

Some say water is not a living thing. But the Sound taught me otherwise. It lives within me. It guided me on a journey that led to composing a heartfelt portrait of the Gulf that resonated with a wide readership. It engendered knowledge to pass on to students in courses that it invited me to create and in the university’s new Gulf Scholars Program that it prepared me to help launch.

Water was an awakening, a revelation, and the future for a kid with a dog.

Jack Davis is a Distinguished Professor of history. His work has earned more than a dozen awards and grants, including a Faculty Enhancement Opportunity Grant, membership in the Andrew Carnegie Fellowship, and a Pulitzer Prize in History for his 2017 book The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.