Faculty in linguistics study how language flows as people adapt to new realities

“How many languages do you speak?”

The lecturer visiting from Guinea thought it was an odd question, posed by a student reporter for the Independent Florida Alligator.

The answer took him a minute to consider: seven.

FIONA MCLAUGHLIN, professor of linguistics and African languages, recalled that the lecturer, like many from West Africa, was highly multilingual. “He said he had never ever thought of counting these languages. It was sort of like saying how many dances do you know? The tango, the waltz, the cha-cha-cha: You don’t count them, you just do them, right?” she said with a laugh.

In fact, counting languages often is tricky. There is no definitive tally of languages spoken in Africa, the richest continent in linguistics, but somewhere around 2,000 is often cited.

“Multilingualism is the norm in the world,” McLaughlin said. “Americans are familiar with bilingualism, particularly here in Florida where we hear so many Spanish speakers or Haitian Creole speakers. But when you go elsewhere in the world, especially in Africa, many people have quite extensive repertoires, maybe fve or six languages.”

People speaking different languages often live close together, and there is a long tradition of migration, trade, and other interchange among groups in Africa.

“So when people are moving, they are determining what languages become useful to them and which ones are no longer useful. They’ll adjust accordingly. It’s really a function of people’s biographies and experiences,” McLaughlin said.

Echos of mother tongues reverberate across the water

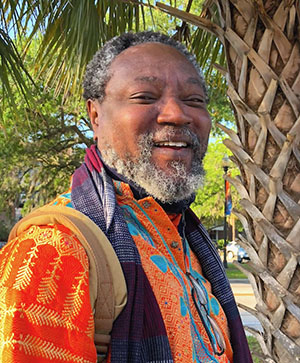

How people use languages, and how they are perceived by others, is a field pursued both by McLaughlin and by KOLE ADE ODUTOLA, associate instructional professor in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures. Both also are Africanists, studying the cultures and dynamics, particularly in West Africa, which has seen large migrations to Europe and North America.

“When people leave their homeland and move somewhere else, they still try to express themselves in the language of their parents,” Odutola said. “But some parts of their native language are not directly translatable.”

“One example is the word ‘with,’ as in ‘I am speaking with you.’ You can’t translate that directly into Yoruba,” said Odutola, speaking of a language predominant in his home nation of Nigeria.

Echoes of African languages can be found in the sound of words and the structure of phrases in English, Caribbean dialects, and other languages infuenced by the “forced migration” of Africans through the slave trade. Odutola points to “ire” (ahy-ree) in Jamaican Patois, which can be loosely translated as “cool” or “ok.”

“This word comes from a word of blessing in the Yoruba language. It’s almost the same spelling, but in Yoruba, the ‘ahy’ is pronounced as ‘ee,’ so we say ‘ee-ree’,” he said.

“We talk about language contact and conflicts. Where there is a predominant language or the language of the colonizers, when it comes in contact with the language of a people, there’s going to be some modification or what people call ‘creolization’.”

This can also affect how language is structured. Odutola pointed to what is sometimes called “Ebonics,” phrasing used by some African Americans. “When you hear someone say ‘Where you at?’ — that is not traditionally proper English. But that structure mirrors Yoruba. So this recalls the structure from the homeland,” Odutola said.

McLaughlin’s research confirms the evolving dynamics, particularly as new forces such as climate change displace populations in Africa and globally. She has begun to explore “eco-linguistics,” the intersection of ecology and linguistics, and plans to launch a course in this area in the upcoming fall semester.

The course will explore climate change discourse, societal views on humanity’s relationship with the natural world, and the role of language within these constructs. It will also explore language endangerment, particularly in ecosystems where communities are compelled to disperse and potentially abandon their original languages due to events such as climate change-induced migrations.

Nevertheless, the prevalence of multilingualism in Africa shows the value placed on linguistic diversity and the willingness to bridge linguistic barriers. When people are forced to leave their communities and are scattered across different regions, the ability to communicate in multiple languages becomes crucial for displaced individuals to navigate their new surroundings and connect with locals.

“For a lot of Africans, multilingualism is something that they use in everyday life,” McLaughlin said. “You see a neighbor coming by who speaks a diferent language than your own native language and you greet them in that language, just out of solidarity and showing respect to them.”