Two UF alumni archaeologists unearth the home and legend of a freed African Muslim slave who became a financier in Georgetown at the turn of the 19th century.

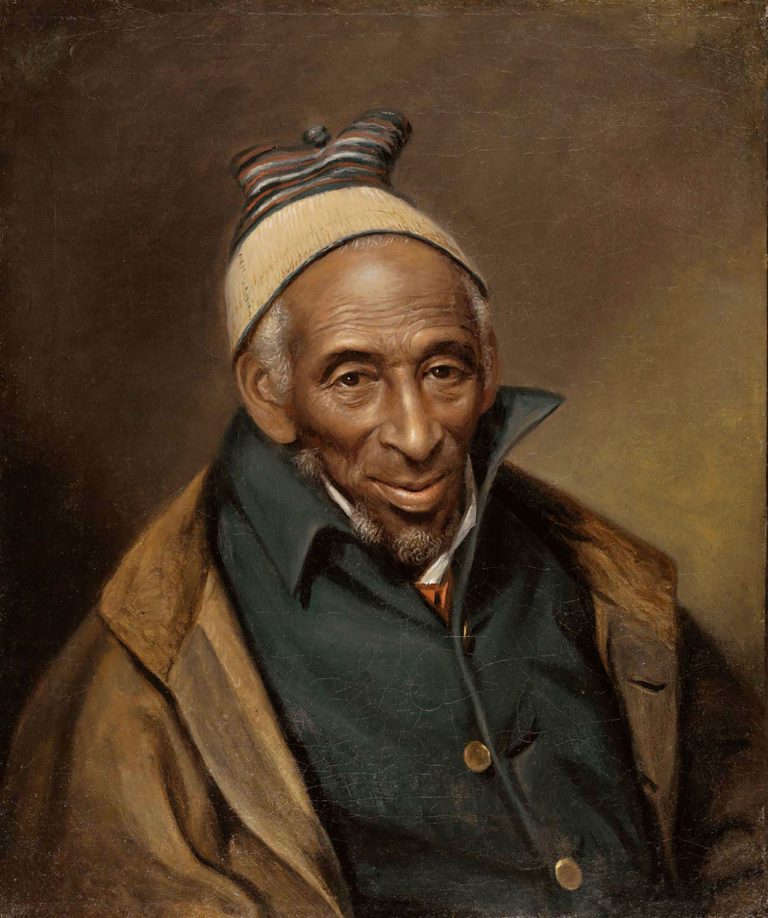

Among the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s collection of 19th-century oil portraits of esteemed men, one stands out. Painted by Charles Willson Peale, who also captured luminaries such as George Washington, it is an 1819 portrait of an older gentleman with a traditional Muslim kufi and a worn but triumphant gaze hinting at an unusual piece of Washington, D.C., history. The painting is of Yarrow Mamout, a financier who sat for two such portraits and owned a sizable property in the Georgetown neighborhood. His remarkable success might be unexpected, as he spent 44 years a slave.

Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro), Charles Willson Peale

Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro), Charles Willson Peale

Archaeology has a way of fleshing out what written records have not. The excavations brought a physical reality to the legend of Mamout.

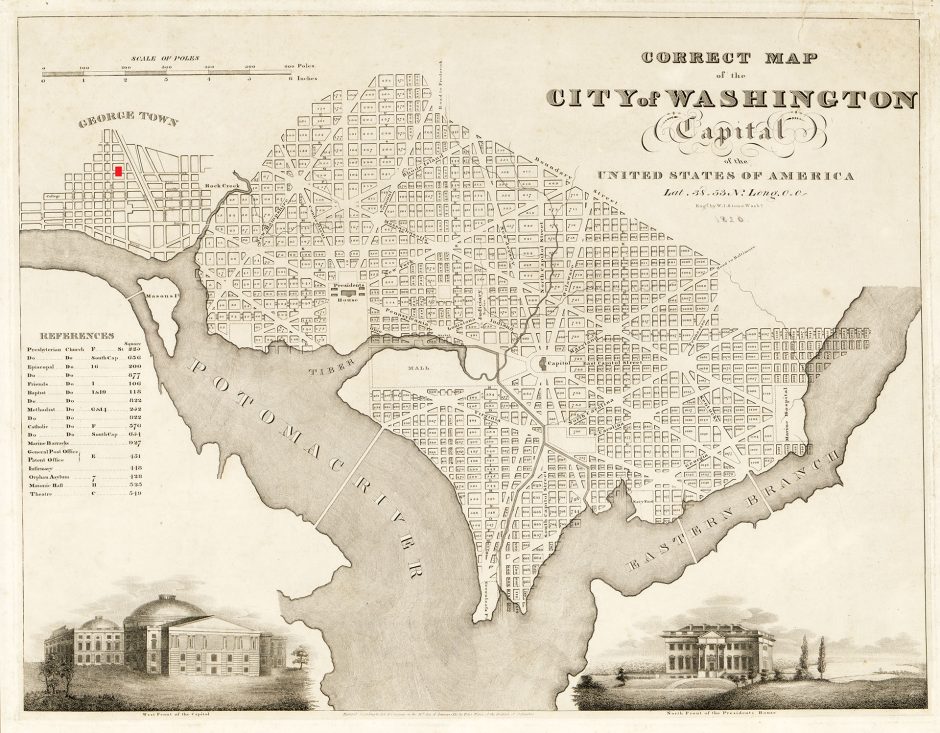

Despite his accomplishments as a freed African Muslim, Mamout faded from history, relegated to the two portraits and local lore. In 2004, his biographer, James H. Johnston, spotted Mamout’s second portrait, a James Alexander Simpson work at the Georgetown Public Library, and he wanted to know more about the man in the picture. Two blocks away, at 3324 Dent Place NW, a small lot is a mystery of rubble, its Reconstruction-era house crushed by a tree as Johnston was finishing his research. Although the legend of Mamout permeated the area, the link between the smiling man in the Peale portrait and the decrepit lot was unconfirmed until Johnston completed his work. The D.C. Historic Preservation Office began excavating the former site of Mamout’s home in June 2015, following several years of research by the office’s interns.

For one graduate student at UF, the excavation was an extraordinary opportunity, and in the face of persistent racial and religious tensions in America, a chance to flex archaeology’s muscles to tackle a pressing social problem. Mia Carey PhD’17 initially came to UF on a McKnight Fellowship to pursue zooarchaeology under the mentorship of Professor Susan deFrance. As she moved forward in her studies, she began volunteering with the D.C. Historic Preservation Office in 2011, with internships in 2014 and 2015. The district archaeologist, Ruth Trocolli PhD’06, invited Carey to join the dig on Dent Place. “We didn’t really know what to expect. Nobody had ever excavated a known African Muslim site in the U.S.,” says Carey, who served as a field director on the dig. Trocolli told The Washington Post that in lieu of time travel or written records, archaeology illuminates the stories of slaves’ lives.

These stories are not well documented in history, and those of African Muslims taken as slaves even less so. Mamout was well educated, which afforded him some reprieve from harsh conditions, although he was kept in servitude for most of his adult life as a brick-maker and butler. In 1800, a few years after gaining his freedom at age 60, he purchased 3324 Dent Place NW. After his death, the house was eventually replaced by another, which sat empty until an oak crushed it in 2011, trapping artifacts of a fascinating life in the ground below. The Historic Preservation Office prevented the permanent obscuring in the face of potential development; a common role for contemporary archaeologists is to uncover secrets in the soil before new construction covers them up. This case was indeed a chance to give voice to the voiceless, as Trocolli put it.

According to Johnston’s research, it was likely that Mamout had been buried on the property; his remarks on this possibility at a development board hearing helped secure the stay on renovations. The dig commenced with mixed feelings about the potential discovery of human remains on the property, reported The Post, but none were found, likely due to the acidity of the clay-based soil. Moreover, the archaeologists found no evidence of burial.

Archaeology has a way of fleshing out what written records have not. The excavations brought a physical reality to the legend of Mamout. However, “the sometimes overemphasis on artifacts, data, and reports is what limits our ability to connect the past to the present in real and meaningful ways,” says Carey. Importantly, the excavation allowed the team to conduct public outreach that challenged the often reductive and sanitized narrative about both slaves and Muslims in American history. The researchers hosted “fence talks” with passersby during the dig and launched a Facebook page, the Yarrow Mamout Archaeology Project, to share their findings and tell Mamout’s story in an innovative way.

According to the dissertation Carey wrote from her Georgetown fieldwork, the excavation was much more than digging holes. There now was an opening to “puncture the silences” created by “white privilege” in society — the “common thread through literacy tests, immigration, South Asian religious movements, the Nation of Islam, and the racialization of Islam,” she says. Excavating Mamout’s residence brought material culture into conversation with oral history and ethnography, filling in the many blanks that speckle America’s convoluted and brutal history of slavery. Although Mamout’s story was unusual, it illustrates that freed slaves did not vanish from society, and their threads of history are crucial to understanding the artifacts, both material and ideological, of race relations in the United States.