UF duo illuminates untold multilingual and immigrant stories

A UF English professor and College of the Arts student spotlight overlooked narratives through a fusion of research and community engagement

Laura Gonzales’ family moved to the United States during her childhood to pursue a better life. Her family chose to move to Florida because the weather was most like their home city in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Yet, one prominent aspect was not the same — the language. Facing challenges as a non-native English speaker, Gonzales later championed the intellectual efforts of language learners.

“They are doing so much mental work just to be understood and get through the day,” Gonzales said.

Inspired by her polyglot mother, Gonzales pursued language studies in higher education. Now a UF English professor, her research and teaching are grounded in community work, language diversity, and technology. Recently, she co-created a museum exhibit challenging assumptions about the perceived lack of necessity for language access in rural communities like Gainesville. This was achieved by showcasing personal immigrant stories from residents of North Florida.

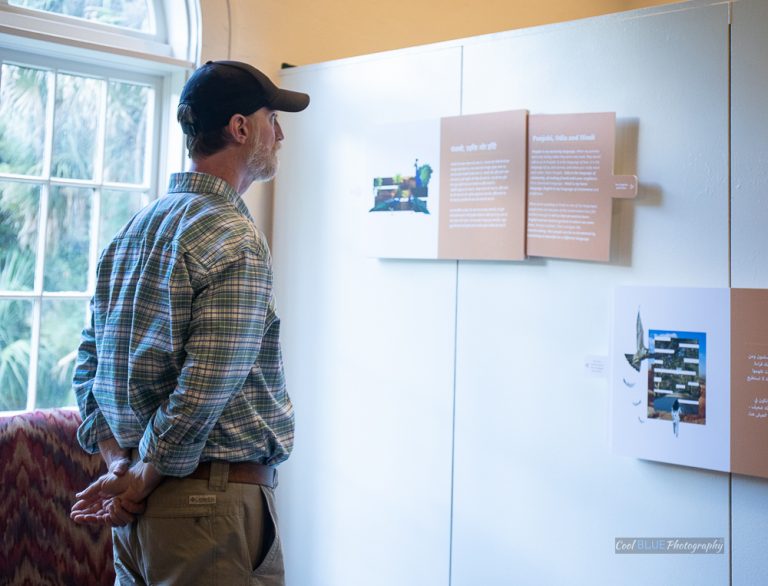

In collaboration with the Rural Women’s Health Project, the Gainesville Immigrant Neighbor Inclusion Initiative (GINI), and Fulbright Scholar and UF College of the Arts (opens in new tab) MFA in Design and Communications student Valentina Sierra Niño, Gonzales and her collaborators address the underrepresentation of North Florida’s immigrant communities in a Matheson History Museum (opens in new tab) exhibit, “We Are Here: Stories from Multilingual Speakers in North Central Florida.” Through 80 interviews, the group created something for and with the North Central Florida community using their stories.

“It’s a project that started because we wanted to highlight something we think is overlooked, which is the linguistic diversity of our region,” Gonzales said.

Gonzales and Sierra Niño explored their languages, countries of origin, and experiences speaking their native language in North Central Florida. Sierra Niño spearheaded the exhibit’s design with a striking collage series of ten pieces, representing ten countries, featuring birds and plants from interviewees’ hometowns to symbolize their immigration journey.

“We used collages as a common ground to create interpretations and explore stories even when we come from different cultures and speak different languages,” Sierra Niño said.

Surprising findings, like Mandarin Chinese being the most spoken language after English in North Central Florida, challenge stereotypes. Gonzales stresses immigrants’ integral role in the community, fueling conversations about marginalized populations’ experiences, strengths, and needs.

“The idea of being a collective and working better together is central to what the exhibit is trying to do,” Gonzales said.

The exhibit fostered connections among immigrant communities, bolstering trust and fellowship. Gonzales saw people connecting with shared community stories, recounting a Ghanaian family’s surprise at finding a collage about Ghana’s languages, history, and culture in a Gainesville museum exhibit.

“I find the most rewarding moments in this project are when people feel recognized, understood, and realize that someone considered them in discussions about immigration, a topic often overlooking their experiences,” Gonzales said.

She highlights an exhibit story of a Guatemalan family speaking Q’anjob’al, a Mayan Indigenous language. The parents are preserving their language and culture by teaching their children Q’anjob’al, while the children teach them English.

“I think it’s great to see how through the immigration journey, people find ways to learn and grow and expand while also remaining true to who they are,” Gonzales said. “I think that’s a good lesson for everybody.”

Gonzales’ award-winning book, Designing Multilingual Experiences in Technical Communication (opens in new tab), extends her commitment to community engagement, addressing inclusive digital experiences for multilingual users through three community language-focused projects.

Rooted in her user experience (UX) design research, the book delves into language diversity’s impact on global research, featuring case studies from the United States, Mexico, and Nepal. Gonzales offers frameworks and best practices for justice-driven, participatory research with multilingual communities, emphasizing current translation practices.

Acknowledging her research privilege, she teaches others to factor it in when developing tools and technologies. She also emphasizes that technologies should enhance, not replace, human connections in multilingual contexts.

“We incorporate technologies into our lives to make things quicker and more efficient. Language doesn’t always work like that,” Gonzales said.

She stresses the importance of building trust and understanding the cultural context of a community when working in multilingual settings before jumping into language translation.

In her professional communication, digital writing, cultural rhetoric, and social media courses, Gonzales integrates community engagement. Students contribute thoughts on the “We Are Here” exhibit, collaborate with the Rural Women’s Health Project, and publish immigrant stories.

“I stress to students, even if briefly in Gainesville for school, they’re here because the community makes it possible. Understanding the community and the university’s role is everyone’s responsibility,” Gonzales said.

Her consulting business, Language Access Florida (opens in new tab), connects Indigenous language translators in Latin America with U.S. organizations needing translation work, mediating between agencies and Indigenous language advocates.

Continuing to raise awareness about Florida’s immigration issues remains Gonzales’ focus.

“In the humanities, we bring together multiple forms of communication to create messages that change the world,” Gonzales said. “That’s what I want to do with my whole life and inspire students to do.”

Go behind the scenes to explore the artist’s process here. (opens in new tab)

Read more from the Fall/Winter 2023 issue of Ytori magazine.