New Book Challenges Long-Held Beliefs About Poverty and Crime

UF sociologist Rebecca Hanson unravels the paradox of violence in Venezuela

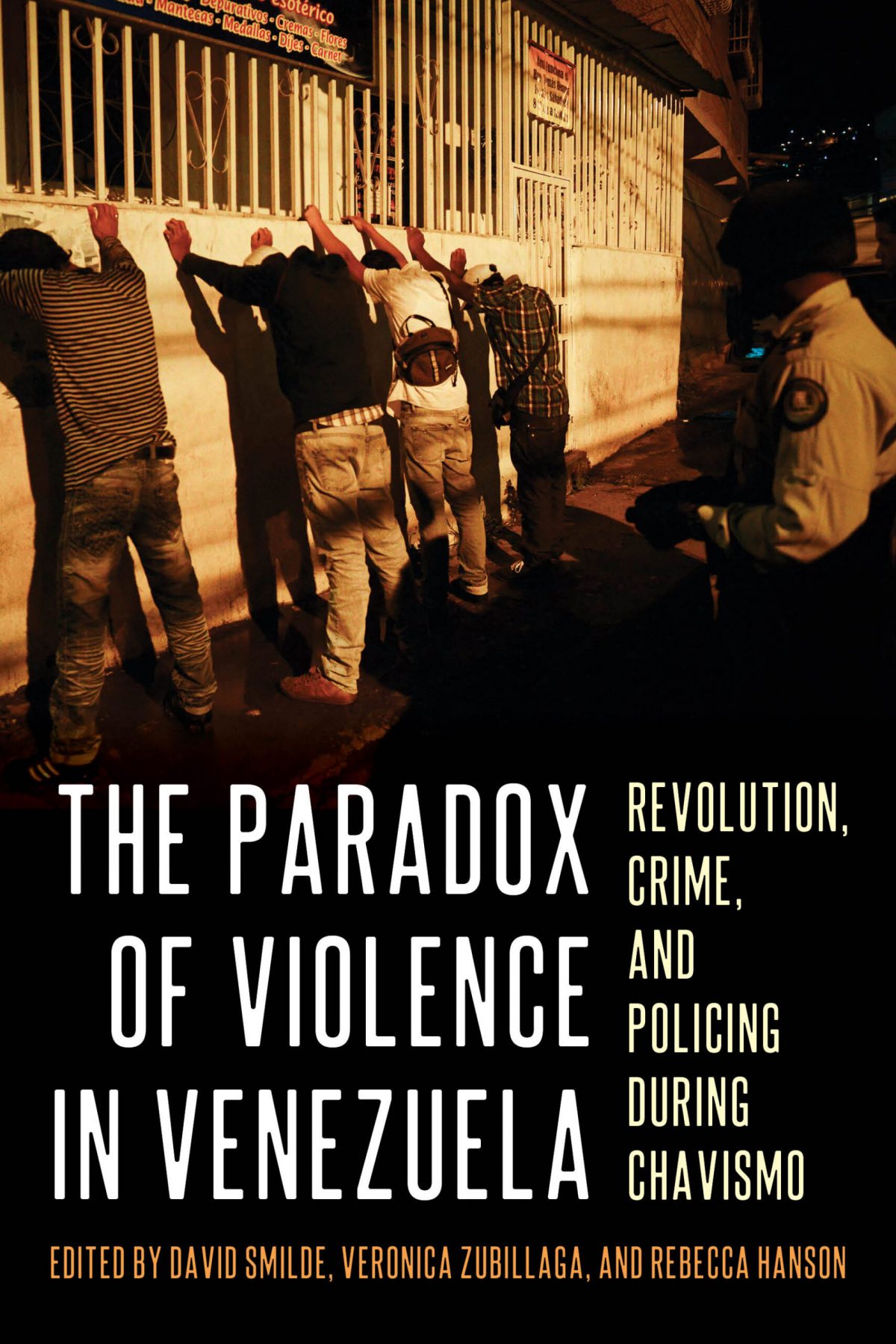

In a groundbreaking new book titled The Paradox of Violence in Venezuela: Revolution, Crime, and Policing During Chavismo, UF sociologist Rebecca Hanson and her co-editors present a comprehensive analysis of the intricate relationship between poverty, crime, and governance in Venezuela. The pioneering work, the first English-language book on these topics, unveils startling insights into the surge of violence despite reductions in poverty and inequality during Hugo Chávez’s presidency. This paradox challenges conventional wisdom, upending long-prevailing sociological and criminological theories.

Seven years ago, Hanson and co-editors embarked on a journey to unravel the intricate puzzle presented by the Venezuelan case. At the time, Venezuela was grappling with the distinction of being one of the world’s most violent countries, while the government simultaneously made strides in diminishing poverty and inequality throughout the nation.

“This inverse relationship — less poverty and more violence — contradicts much of the classic criminological and sociological scholarship,” Hanson said, “as well as popular understandings that poverty creates crime and violence.” Hanson teamed up with co-editors David Smilde (Tulane University) and Verónica Zubillaga (Universidad Simón Bolívar in Caracas) to contend with the stark contradiction to prevailing theories.

The resulting volume, authored by a team of esteemed scholars, sheds light on four pivotal factors that contributed to the surge in violence under the Chávez administration and the administration of his successor, Nicolás Maduro. First, unprecedented oil revenues flooded the state’s coffers, inadvertently diminishing institutional capacity and increasing impunity. Second, revolutionary governance led to internal strife within the government and ruling party. “These political clashes diminished not only the state’s capacity but state actors’ interest in intervening in key areas of citizen security — such as gun control and judicial and penal reform,” said Hanson. Third, a wavering commitment to a civilian police reform saw the resurgence of militarized policing, which resulted in an increase in police violence. Finally, poverty reduction strategies failed to address concentrated disadvantage, a convergence of various structural conditions linked to crime and violence.

Some of the book’s contributors have spent decades thinking about how to reduce crime and violence in Latin America, says Hanson. However, violence in Venezuela has only garnered attention from a handful of researchers, as research efforts have dwindled in the face of the nation’s economic and humanitarian crisis. The book seeks to showcase the significant research initiatives undertaken by Venezuelan scholars within the nation. Hanson notes that the editing process took longer than usual because six of the chapters were originally written in Spanish.

“Translating so many chapters added a lot of additional steps,” she said, “but we are incredibly proud that non-Spanish speakers now have access to incredibly important research that was previously out of reach due to language barriers.”

Despite enduring political polarization between those who support and those who oppose the Chavista government in Venezuela, notes Hanson, the study transcends the constraints of political divisions. “Of all the different lines of social scientific research, investigation of violence is one in which researchers have been able to cross political lines to collaborate,” she said.

The authors are hopeful their empirical analysis will guide public discourse and policy formulation, shifting the issue of citizen security into a realistic discussion of how security and safety can be established. They urge stakeholders to recognize that violence is a structural rather than an individual-level issue. The book contends that sustainable solutions lie in policies that foster trust, knowledge, accountability, and social cohesion at multiple levels.

In the final chapters of the book, the authors propose support for local activism and civil society, criminal justice reform, changing the use of urban space, engagement with at-risk youth, and situational crime prevention. According to Hanson, these strategies could all contribute to a reduction in crime and violence.

“We see the book contributing to long-standing debates in the social sciences beyond Latin America,” said Hanson. “These chapters reveal a need to reorient how we think about violence and its relationship to poverty, inequality, and the state.”

Learn more about the new book here.