UF and Kuikuro Tribe Join Forces to Preserve the Amazon

UF anthropologists partner with an Indigenous tribe to fight for a sustainable future

In 1993, anthropologist Michael Heckenberger made his first journey to visit the Kuikuro, an Indigenous group living in a remote territory of southeastern Brazil. He traveled from Rio de Janeiro by plane, bus, and flatbed with Chief Afukaka and his young son Amuneri, following their months together at the UN summit Rio-92. Upon arriving on the bank of the Xingu River, they packed a motorboat, a first for the Kuikuro villagers, for the 12-hour journey downriver.

After a midnight arrival at the riverbank port of the Kuikuro, many of the villagers helped carry supplies for his year-long stay the six additional miles down the road. Wading through neck-high water along the way, Heckenberger recalls, “I was thinking some giant Amazonia gator, jacaré, or prehistoric snapping turtle would emerge to snatch me away.”

He remembers the moment he emerged from the river: The Kuikuro village, a circle of houses around a large central plaza, their thatched roofs bathed in soft blue moonlight, came into focus. It was hard not to feel like you were stepping back in time, he said.

When he first lived with the Kuikuro in 1993, according to Heckenberger, the Amazon was the “biggest black hole” in the world of archaeology. But it didn’t take long to become well acquainted with the Amazon’s land and creatures: He’d soon encounter massive anacondas, battle malaria, and suffer from bot flies laying eggs in his skin. He even carried a sidearm on solo treks through the brush, at the request of the Chief, prepared to fend off jaguars or other dangerous fauna.

“The Amazon is a character in every visitor’s story,” he said. As a lived experience, “it swallows people whole.”

It has also been full of surprises for Heckenberger, who has been given a rare chance to gain a deep understanding of the Kuikuro’s traditional practices and cultural heritage in a partnership spanning three decades.

Over time, he has developed a particularly close bond with Chief Afukaka Kuikuro, the principal Chief of the Kuikuro Indigenous Nation. He estimates that he lived about three years of his life in the Chief’s house. He refers to the Chief as his “teacher, friend, and brother.”

Their partnership took time and patience. At first, the Kuikuro leaders hesitated to welcome him into their village. But Heckenberger worked closely with the community to ensure projects reflected their priorities and concerns, presenting ideas that benefited all. Building on the Kuikuro’s local knowledge and oral histories, he worked with them to map ancient settlements, roads, and ditches using state-of-the-art mapping, GPS, and GIS, connecting the dots to the cultural heritage of the Kuikuro people.

“I was wary of researchers,” Chief Afukaka said. “But as I started to understand the archaeology and maps, I started to see how it could help us.”

With mutual respect, the partnership flourished. Heckenberger pushed Kuikuro history back to before 500 years ago — eventually digging even deeper to show their connections to the land 2,000 years ago. The scientific approach helped the Kuikuro establish their rights to the lands they inhabit. “Archaeology is a powerful tool to show that our people have been on the lands since primordial times,” said the Chief’s son, Amuneri.

“We want to be protagonists of our own history.”

— Kalutata Kuikuro

As he continued to map Amazonia over the years, Heckenberger also helped deliver one of the great scientific revelations of the 21st century: The Amazon is not a primordial wilderness.

This research, the first to demonstrate that the Amazon had its own model of urbanism, uncovered large towns and chiefdoms. Heckenberger exposed extensive remnants of an urbanized network of settlements and, in the process, an Indigenous nation’s hidden history of sustainability was unearthed, too.

It was long assumed that Amazonian soils prevent intensive agriculture and, thus, large populations. But the maps and excavations revealed a landscape transformed by humans. He discovered “garden cities” among the settlements engineered to combat dry and warm weather periods with careful forest management. We have much to learn from these models of climatic resilience, Heckenberger noted.

Ancient Amazonians learned how to work with the lands to create more fertile soils, carefully managing the forest by grouping trees and concentrating a few species together. It’s now believed that much of the jungle’s biodiversity may have been carefully crafted by the Indigenous communities themselves: the ancestors of the present-day Kuikuro. It’s a hopeful reminder as we enter a period of terrible destruction for the Amazon: Humanity and the rainforest can coexist — after all, they lived in harmony for millennia.

In 2020, Heckenberger and the Kuikuro turned from mapping the history of their ancestors to safeguarding the future of their tribe. Epidemics had wiped out large portions of their populations in the past, so as the Kuikuro faced the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic, they knew what was at risk. They partnered with Heckenberger and others to employ the ESRI GIS software-based application used for the cultural heritage work, which allowed the community to track movement in and out of the village. In no small feat, this contact-tracing collaboration and associated medical supplies and personnel and community needs kept pandemic-related deaths or hospitalizations to zero in the eight Kuikuro and related Indigenous communities.

As the Kuikuro fight to maintain their traditional ways, they understand that change is necessary. “We have to live in both modern and Indigenous worlds to not lose ourselves,” said Chief Afukaka. The community uses these tools as much to preserve their culture as move it forward, Heckenberger said. They don’t want their culture to disintegrate.

Today, the tribe has a front-row seat as the Amazon teeters on the edge of a “tipping point” of destruction, essentially living at ground zero of an irreversible transition from tropical forest to a non-forested ecosystem. The Kuikuro territory is under threat from all sides: Wildfires encroach on their lands, catastrophic droughts threaten crops, deforestation increases erosion and erases habitats, and public health is compromised by water pollution.

“It’s unthinkable to me that there may not be an Amazon forest around in my lifetime,” Heckenberger said. “The best solution could be to put the charge in the hands of Indigenous peoples — they have all this knowledge to share.”

As modern challenges infringe on the tribe’s territory, an urgent need to recover their ancestral techniques has emerged. The Kuikuro are looking back to their ancestors for guidance on how to survive in this rapidly changing climate. “Previous generations knew by the stars when to plant,” Chief Afukaka said. “Now the younger generation doesn’t even know how to plant at all.”

Heckenberger visited the Kuikuro last August, together with anthropology professors Hyatt and Cici Brown Professor of Archaeology Kenneth E. Sassaman and John Krigbaum, to participate in the annual kwyrp, the sacred feast for deceased chiefs, and extend the invitation to visit and participate in UF Indigenous initiatives.

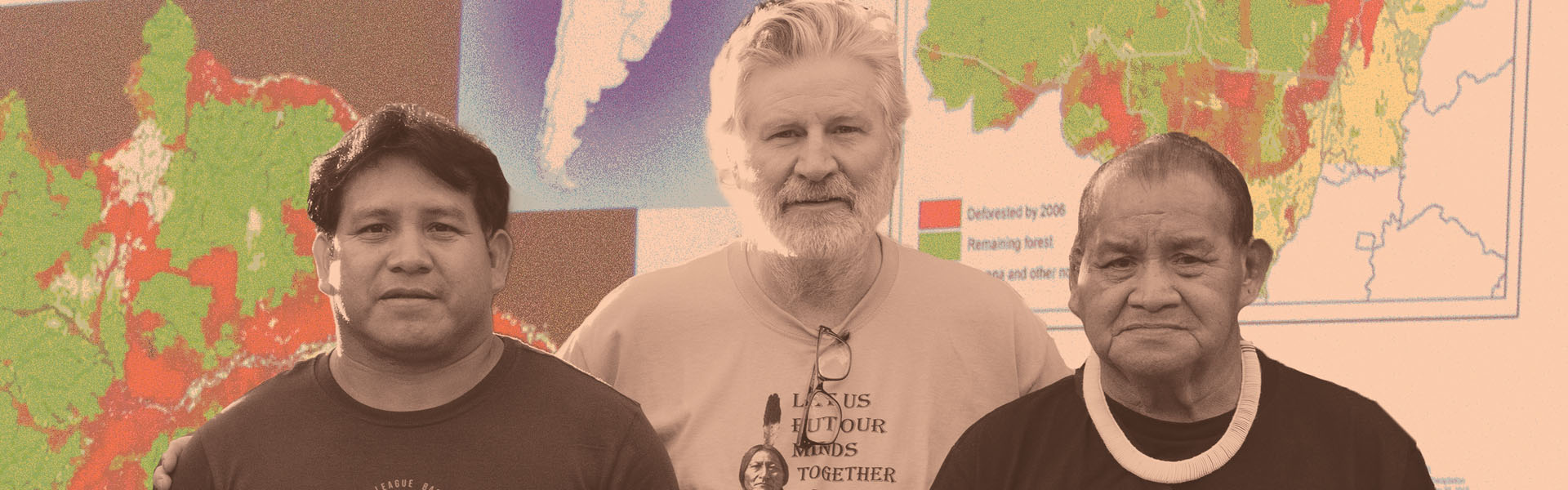

In February, Heckenberger brought several leaders of the Kuikuro tribe, representing three generations of collaborators on the UF projects, to speak at the University of Florida to encourage future partnerships. The public event was sponsored by the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program and the Department of Anthropology. The large meeting room was packed to the brim, with students, faculty and community members filling in every available space.

As Chief Afukaka Kuikuro and his heirs took their seats at the front, a captivated audience fell silent. Sassaman and Heckenberger gave minimal introductory comments, turning the stage over quickly to ensure the Kuikuro voices took precedence.

“We have to live in both modern and Indigenous worlds to not lose ourselves,” said Chief Afukaka.

The Chief’s oration was delivered in his native Carib language and translated to Portuguese, with help from his heirs. Archeologist Helena Lima, a collaborator from the Museum Goeldi in Brazil, translated their discussion into English. She currently directs the group’s collaborative project, the Amazon Hopes Collective, from Brazil.

The project draws together the Kuikuro, scholars, and scientific consultants to address current problems, including forest fires, food security, and pollution. Their long-term goal is to protect Indigenous groups across the Xingu region from external threats and preserve their way of life by connecting them with the global community.

As heir to the chiefdom, Amuneri is concerned about the challenges ahead. “My father is old, and I’m worried about taking the knowledge and wisdom of my father forward,” he said. “As a chief, I’ll have a great responsibility to maintain the culture.

The Chief’s grandson, Kalutata, has developed his own strategies to preserve their culture. As president of the Kuikuro Indigenous Association (AIKAX), he uses film and audiovisual production to encourage Indigenous peoples of the Amazon to create first-hand content of their experiences and daily lives. It’s a deeply personal approach to activism. “We want to be protagonists of our own history,” said Kalutata.

On the global stage, Heckenberger calls for more space to be created for Indigenous peoples to share their knowledge with scientists. It’s not just about the past — it’s about coming together for the future of the Amazon. He hopes to invite Kalutata back for a semester or two to study and interact with UF students and faculty.

“The Kuikuro are committed to preserving the rainforest for future generations,” Heckenberger said. “They can guide the path forward.”

Explore Kuikuro culture with the Amazon Hopes Collective here.