Astronomers find the first binary–binary.

Everything we know about the formation of solar systems might be wrong, say Professor of Astronomy Jian Ge and postdoc Bo Ma. They’ve discovered the first “binary–binary,” or two massive companions around one star in a close binary system — one so-called giant planet (12 times the mass of Jupiter) and one brown dwarf, or “failed star,” with 57 times the mass of Jupiter.

Astronomers believe that planets in our solar system formed from a collapsed disk-like gaseous cloud, with our largest planet, Jupiter, buffered from smaller planets by the asteroid belt.

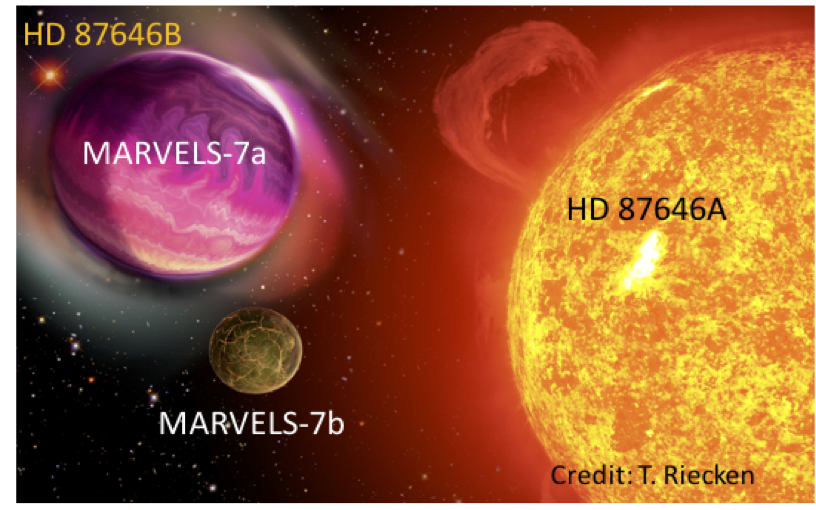

The binary system HD 87646’s primary star is 12 percent more massive than our sun, yet is only 22 astronomical units away from another, smaller star. In addition, the giant planet and brown dwarf are orbiting the primary star at about 0.1 and 1.5 astronomical units, respectively. An astronomical unit is the mean distance between the center of the Earth and our sun — in cosmic terms, a relatively short distance. The stability of the system despite such massive bodies in close proximity raises new questions about how protoplanetary disks form.

Artist’s rendering of a close binary system.

Astronomers believe that planets in our solar system formed from a collapsed disk-like gaseous cloud, with our largest planet, Jupiter, buffered from smaller planets by the asteroid belt. In HD 87646, the two giant companions have accumulated far more dust and gas than what a typical collapsed disk-like gaseous cloud can provide, so they were likely formed through another mechanism.

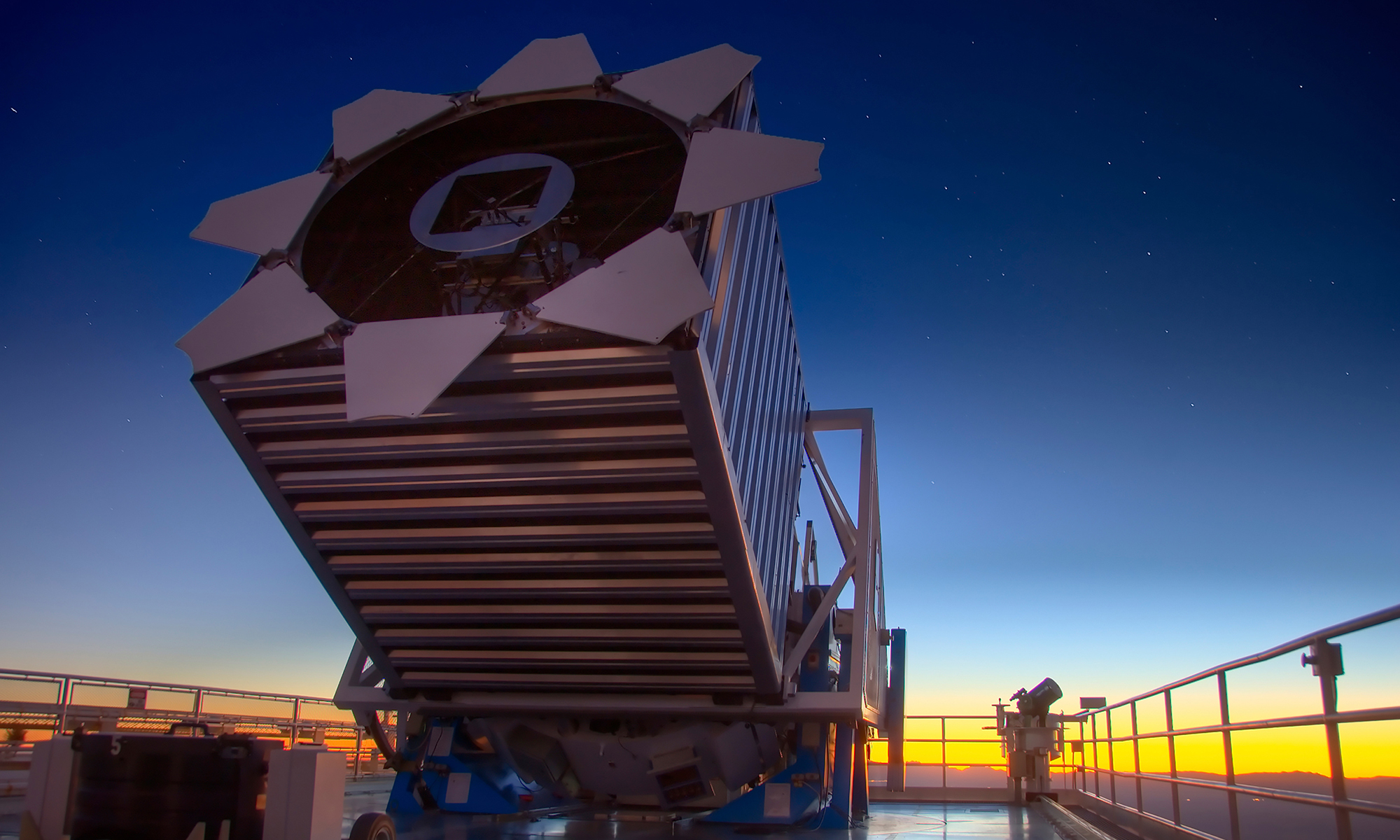

The system was found from the 2006 MARVELS survey by the Doppler-based W.M. Keck Exoplanet Tracker, or KeckET, which was developed by Ge’s team at the renowned Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) telescope in New Mexico. KeckET is unusual in that it can simultaneously observe many celestial bodies. “A typical [Doppler] project involves one object, one planet,” explains Ge. This discovery would not have been possible without KeckET, he says. It has taken eight years of corroboration from over 30 astronomers at seven other telescopes around the world and careful data analysis, mostly done by Ma, to confirm what Ge calls a “very bizarre” finding. Their findings appear in the November issue of Astronomical Journal.

To support the people, program, or research featured in this story, please visit