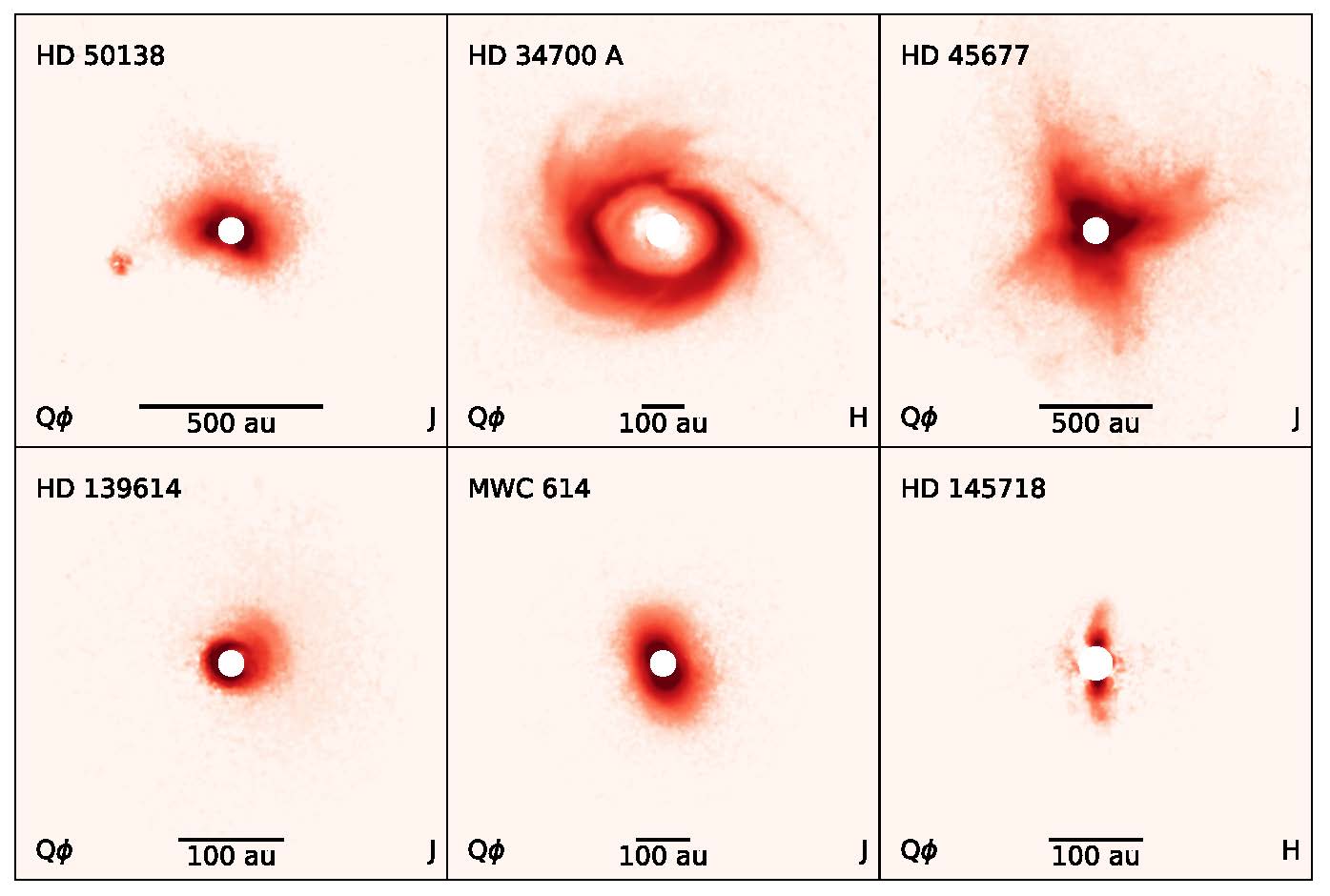

A team of researchers, which includes University of Florida assistant professor Jaehan Bae, imaged 44 targets in a survey called Gemini-Large Imaging with GPI Herbig/T-tauri Survey, or Gemini-LIGHTS. (Credit: Evan Rich, University of Michigan)

Searching for New Planets? These Astronomers Know Where to Look

A team of astronomers make headway in the hunt for distant worlds

A group of astronomers have come up with a new approach to the difficult task of discovering newly forming planets.

The team, which includes the University of Florida’s Jaehan Bae, proposes that rather than searching for individual new planets, astronomers should seek out the environments most conducive to their formation.

The researchers have found that systems with stars less than three solar masses are more likely to have large rings made of tiny dust grains, which can be indicators of planet formation. By looking at such environments, the team may have found a newly discovered planet: The potential planet, which appears to orbit a massive star, is about 13 times the mass of Jupiter.

More observation is needed to determine whether the object is in fact a planet or a brown dwarf star. If confirmed to be a planet, it would be one of just a few exoplanets (planets outside of our solar system) known to orbit a massive star.

A study introducing their discoveries, led by Evan Rich of the University Michigan, has been accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal and will be presented at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting later this month.

Their findings are drawn from observations made using the Gemini South Telescope in Chile, through the International Gemini Observatory, a program of the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab.

“The dust rings, gaps and spiral arms seen by Gemini are telling us how and when planets form in real-time,” said Bae, a planet formation theorist and assistant professor of astronomy at UF. “With more accurate simulations and new telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope and the Extremely Large Telescope, we are zeroing in on the key ingredients to understand how our solar system came to be.”

Read more about the discovery at The University of Michigan.