Small Packages

A team of UF researchers find a unique connection between humans and the Bahamian hutia

Meet the Bahamian hutia. A species of rodent that can reach the size of a full-grown rabbit, they just might hold the key to helping us understand the behavior and lifestyles of indigenous humans in the Bahamas.

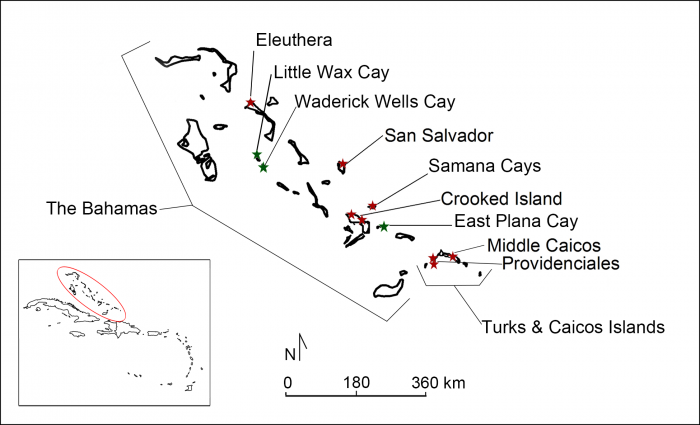

In a study published in PLOS One, a group of researchers from UF share their findings that these hutias were physically moved from their native Bahamas to the Turks and Caicos Islands by the Lucayans, the indigenous people who once called the islands home. The work was conducted by Michelle LeFebvre and William Keegan from the Florida Museum of Natural History, Susan deFrance and John Krigbaum with the Department of Anthropology, and George Kamenov from the Department of Geological Sciences.

For the Lucayans, hutias might have served as something like an ancient Roomba, collecting waste as they roamed around. “When you have those animals in close proximity to humans, they’re benefitting from how humans are using the land,” deFrance said. “They’re consuming vegetation that people are discarding or keeping in their gardens.”

To uncover this connection, the researchers conducted an isotopic analysis of hutia bones and tooth enamel recovered from archaeological sites located in both the Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands. This revealed that some hutia consumed plants cultivated by the Lucayans. The team then analyzed the strontium isotopes of the tooth enamel, comparing the archaeological results with modern hutia skeletal remains that were brought from the Bahamas to live in a museum research lab in Gainesville for several years.

“The hutia that grew up in the Bahamas and moved to Gainesville as live animals had their strontium values change,” Krigbaum said.

What this showed the team was that the hutia — with their unique, ever-growing molars — mirrored the local signature of its immediate environment. This demonstrated the sensitivity of strontium isotopes and the need to be cautious when analyzing archaeological rodent teeth to interpret potential changes in location for various species.

When you have those animals in close proximity to humans, they’re benefitting from how humans are using the land.

The evidence strongly points to indigenous people moving the hutia from the Bahamas to the Turks and Caicos Islands, but the question remains — why? “Changing an animal’s geographic distribution is a big deal,” LeFebvre said. Tragically, the Lucayans were wiped out due to enslavement by Spanish explorers, leaving minimal records and this mystery.

While archeological evidence usually seen in the domestication of other animals — like the remains of pens or posts for an enclosure — have yet to be found on the sites examined in this study, this may be because hutia were simply too slow to demand human containment.

With more papers and studies in the pipeline, the team hopes to shine a light on this period of human history and see what else we might learn from these rabbit-sized rodents.