Remembering a Forgotten National Holiday

UF historian Sean Adams sheds light on an obscure former federal holiday

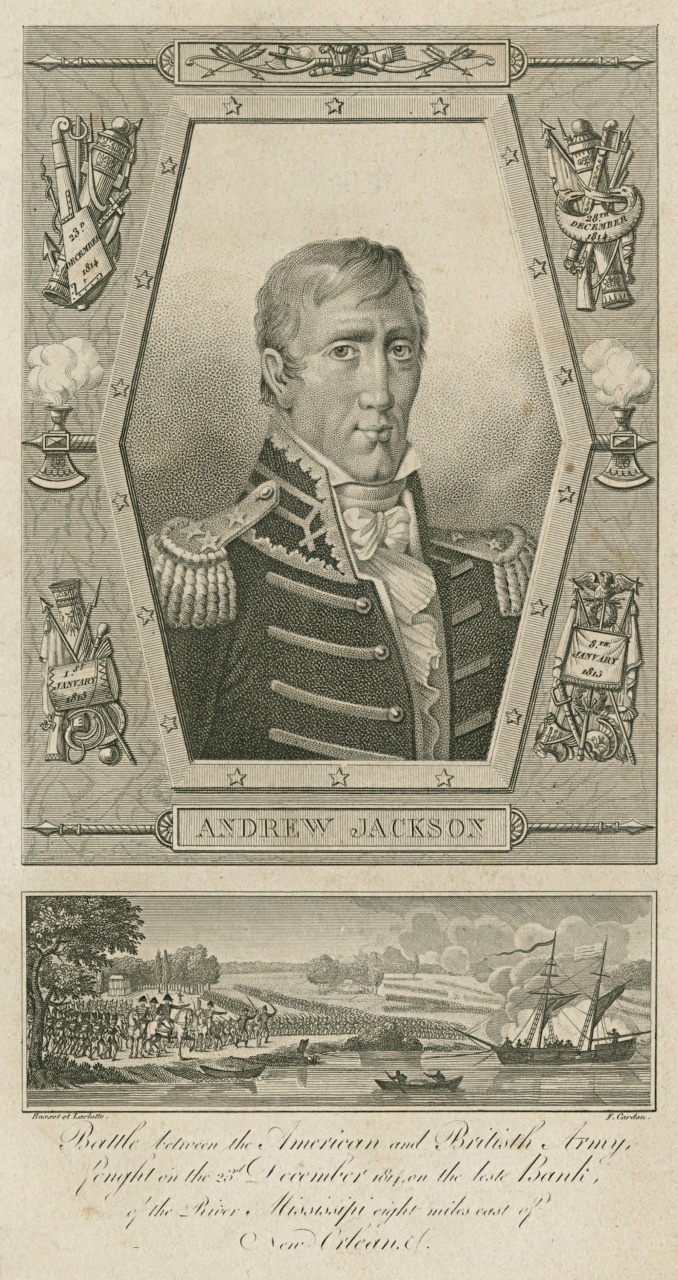

The Glorious Eighth of January, a commemoration of the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, was once celebrated with raucous parades and chest-thumping speeches — but today it has disappeared off Americans’ radar. Why did the United States stop celebrating the Eighth? According to Hyatt and Cici Brown Professor of History Sean Adams, the waning of such a momentous occasion — and the controversial U.S. president at the center of it all — reveals valuable lessons in history and memory.

A commemoration of American defeat over the British at the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, the Eighth stood as a federal holiday for nearly half a century. The holiday was marked by festive and highly anticipated events throughout the nation. But following the Civil War, public enthusiasm diminished as historical memory reshaped the momentous battle, plaguing it with misperceptions.

The largest misconception, which still lingers today, boasts the battle as a pointless engagement. News traveled slowly in the nineteenth century — battle participants had no idea that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed two weeks earlier, ending the War of 1812. However, Adams and other informed scholars stress that the treaty had yet to be endorsed by the Senate: If American troops had not successfully thwarted British invasion of New Orleans on the Eighth, the war would have taken a sour political turn in the U.S. Additionally, the British had not recognized the territorial boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase, so Americans had much to lose if the British army made it over Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson’s lines, explains Adams.

Thankfully, Jackson’s leadership and command of his army held the nation’s territories together in this defining moment. British forces withdraw, never to return, and a surge of patriotism sweeps the nation. Skyrocketing to fame after this moment, Jackson becomes “akin to a national celebrity” according to Adams, transformed into a national war hero of epic proportions. The victory, marking a significant achievement for the U.S. military, ultimately catapults Jackson to the White House and shifts the course of American democracy.

When facing the American public, Jackson styled himself as an “everyman,” using this tactic of relatability to launch himself to power. “Jackson was actually part of the elite class but somehow aligned himself with people who felt they were on the fringes,” Adams said. To elect a military leader (other than George Washington) to office was considered a major departure from the political norm — thousands of people showed up on the day of Jackson’s inauguration in 1829 to rejoice in the new seventh president of the United States.

The White House gates were thrown open to mark the site’s new era as “the people’s house,” and giant tubs of celebratory punch were served to the reveling masses. “People felt a strong attachment to Jackson; they thought he represented their interests,” Adams said. He’s credited with cementing the American democratic mindset, predicated on the American dream of individually powered prosperity.

Yet, the glimmer faded quickly upon Jackson’s death. His dual feats of military might and democratic transformation paled in time, as a sense of inevitability took hold around America’s “destined” success. Posthumously, historians found Jackson underwhelming at best until he came back into favor in 1945, thanks to the release of a book crediting Jackson with an earlier version of the famed “New Deal coalition” that unified marginalized elements of the American electorate. Once this theory was discredited, historians returned to the more critical view of Jackson, Adams explains.

The founder of the Democratic Party is now remembered as a president who fought for the rhetorical “common man” — but he was also a slave owner who inflamed ethnic and racial tensions by advancing anti-Native American initiatives, including the Indian Removal Act. “Jackson shows us you can have this really powerful rhetoric of the common man, but also this dark side as well,” Adams said. “He represents that part of our story where we can see really important advances in our democracy at the same time as it exposes the areas that still needed work.”

Historical reputations ebb and flow; Jackson is not an anomaly. “Presidents are like the stock market – the value of their reputation rises and falls over time” he said. “I taught Hamilton 10 years ago and people thought he was boring until Lin Manuel’s production came out.” But Adams’ students at UF always seem eager to learn more about Jackson’s colorful life — although he admits it’s a challenge to balance every facet of such a divisive and complicated figure. Nothing is black and white when it comes to historical analysis.

“If you look for perfect or uncomplicated heroes in history, you’ll always be disappointed,” Adams said. “And some folks that we dismiss as historical villains can have relatable traits because, after all, both our historical heroes and villains were real human beings.”

To dive into the intricacies, Adams published a volume in 2013 called A Companion to the Era of Andrew Jackson. It’s a collection of 27 original essays by leading scholars and historians, each exploring multifaceted aspects of Jackson and the events that shaped his administration. The volume will be released in paperback edition later this month.

When we talk about history, Adams explains, we’re reconstructing people’s lives. Memory can start to craft its own narrative, so it’s critical to make the distinction between history and memory. “Some people want history to serve this patriotic purpose — as a historian, I’m willing to dive into the complexity of things, while people using only memory often don’t have that luxury,” Adams said.

Although the realities of Jackson’s life have been veiled by the fog of time, his legacy remains woven through the American tale. “Love him or hate him, Jackson had such a strong personality and led such an interesting life,” Adams said. “We’re stuck with him; he’s part of us.” Adams explains that the light and dark parts of Jackson offer a chance to explore who we’ve become and who we wish to become in the future.

“History is not this always expanding circle of ‘we’ and the American story is not one of constant and unrelenting progress,” Adams said. “But there are always lessons to be learned in these moments of turbulent change.”