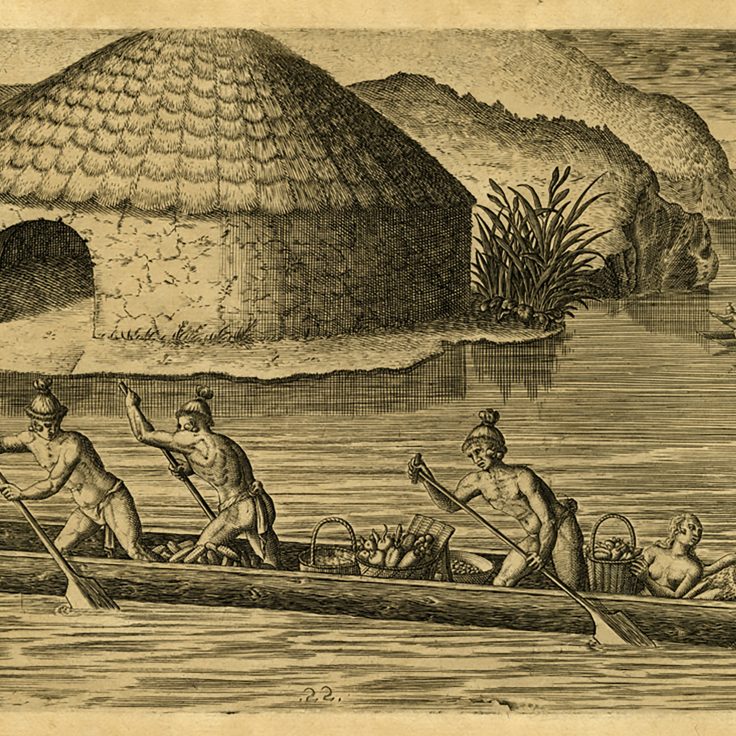

Kuji City, Japan

Personal Essay — The Japan That Can Say Yes

A UF professor discusses what she learned on a study tour to the Land of the Rising Sun.

In the late ’80s, a bold volume titled The Japan That Can Say No appeared on the scene. Penned by Ishihara Shintaro, leading Japanese political figure, and Akio Morita, co-founder of Sony and chairman of Sony at the time, it sought to lead the vanguard of a new, aggressive Japan that would take its rightful place as a world economic power. This was to be the Japan that could be as blunt as the United States, leaving the notoriously ambiguous and agreeable, but unreliable, Japan in its wake. No more slippery expressions like zensho shimasu, which on its surface means something like, “I will take an appropriate step in the matter,” but most often has the intended meaning of “certainly not.”

Author and interpretation researcher Masaomi Kondo discusses the problems such words have posed historically for interpreters in high-level negotiations, such as the 1969 discussions on textile export quotas and the return of Okinawa between President Richard Nixon and Prime Minister Eisaku Sato. In the ’90s, Teresa Watanabe of the Los Angeles Times remarked on the emergence of a new, direct-speaking Japan, citing the example of Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa’s explicit rejection of President Bill Clinton’s demand for measurable trade targets in 1994. Hosokawa’s negotiators did not mince words, stating totei doi dekimasen, or “There is no way I can agree with that.”

So, what do I mean by the title, “The Japan That Can Say Yes?” In December 2015, my colleague at the University of Florida Yasuo Uotate and I served as chaperones to 23 UF students on a nine-day study tour of Japan, with all expenses paid by the government of Japan. Before leaving on our Kakehashi Project study tour, I had fully expected that lecturers and local officials would try to inculcate us on the industrial productivity, cultural vibrancy, and political importance of Japan.

Rather than disseminating propaganda, however, those experts, local leaders, students, and families we met during our trip showed a side of Japan that is willing to say “yes” to joining the global community and facing major sociopolitical challenges. There are several cases in point that will inform my thinking and teaching in the future.

On waste and recycling

Considering Japan’s cultural uniqueness and superiority, I expected to see arguments extolling the philosophy of mottainai (“avoiding wastefulness”) and pointing to the Edo period (1600-1868) as the exemplar. Instead, the speaker directed our attention to, at the personal level, the need to separate out combustible and non-combustible waste, and at the public level, the new facility for burning combustible waste that is designed to fit into the Tokyo cityscape in a bold architectural manner. They also introduced us to the slogan “reuse, reduce, recycle.” Thus, the discussion was not about why the Japanese way is better or even best, but rather the way a small country is dealing with large amounts of waste in an environmentally sound way.

What I sensed keenly is how intimately and deeply our two nations have been intertwined over the past century.

On shared history

Our speaker on Japanese government, Mr. Hideki Yanagi, Senior Coordinator, North American Affairs Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, presented a history of American impact on Japan. He discussed the firebombings of Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka in WWII; the educational, military and land reforms during the U.S. occupation of Japan; the writing of the Constitution of Japan; the Korean War; and the 1960 protests against the Japan–US Security Treaty. Mr. Yanagi also delved into the significance of Article 9 of the Constitution, which renounced the ability to wage war, and on the implications of Prime Minister Abe’s recent reinterpretation that allowed Japan to provide military aid to its close allies. What I sensed keenly is how intimately and deeply our two nations have been intertwined over the past century. Mr. Yanagi did not hesitate to point out that certain pre-war political philosophical differences among government officials and the Japanese people still remain, and stand to affect foreign policy. It was also good for students to hear about Japan’s take on key moments in our shared history, such as General MacArthur’s goal to make post-war Japan “as weak as possible” and not a full-fledged modern democracy.

Statue of the great samurai Kusunoki Masahige at the East Garden outside Tokyo Imperial Palace.

Statue of the great samurai Kusunoki Masahige at the East Garden outside Tokyo Imperial Palace.It was good for students to hear about Japan’s take on key moments in our shared history.

On corporate and government mentality

Our speaker on Japanese politics, Dr. Akira Nakamura, professor emeritus of Meiji University, has extensive knowledge of both the Japanese and US governmental structures, and is the first Japanese member of the US’ National Academy of Public Administration. At the risk of doing an injustice to his highly engaging and instructive talk on Japanese politics, I would like to highlight two cases in point where his critical perspectives on the Japanese government’s reactions and policies surprised me. The first was his exploration of why new political parties in Japan, such as the Democratic Party of Japan, have not been able sustain their successes in leadership. The DPJ, in office in 2011 during the tsunami and nuclear disaster at Fukushima of March 11, delayed until March 18 their announcement to mothers with infants that they should not use tap water, thereby causing much distress for new mothers, and also a rush on bottled water that resulted in total depletion of stocks. In Professor Nakamura’s view, the DPJ was incapable of dealing with a disaster. The other case highlighted the costs of the traditional sacrifices made to personal life in throwing one’s priorities to one’s employer — an American Hanshin Tigers baseball player was not permitted to go home upon learning that his son in the US had developed a tumor. When the player did so, he was fired from the team. Here, rather than highlight the strengths of the Japanese government, or of the Japanese corporate mentality, Professor Nakamura chose to give examples of weaknesses and points of contention.

How these two talks relate to my impression of the Japan that can say “yes” is that I found leaders in the public domain outlining not the superiority or uniqueness of Japan, but rather elaborating on the ways in which Japan’s relations with other countries have shaped the nation that Japan is today — a nation that is no better than other nations and that, like other nations, has the potential to take a number of different paths into the future. I also found these speakers challenging our students to always understand that there are costs and benefits to any policy and that opposing parties will see things differently. I found a Japan that said “yes” — we face problems just like you, but starting a dialogue with others may be the best way to figure out its path.

Amarin, the “yura-kyara,” or mascot character, of Kuji City

Amarin, the “yura-kyara,” or mascot character, of Kuji City

The tour leaders did not seek to deploy the soft power of Japanese manga and animation.

On Kuji City

The tour leaders did not seek to deploy the soft power of Japanese manga and animation. The cultural perspectives on our study tour were local, those of Kuji City in the Iwate prefecture. The woman in charge of the tourism promotion office presented a lecture on the region’s characteristics. A great speaker with excellent English, she confided to me during one of the breaks that she was a single mom. The region, like many others in Japan, suffers from decreasing birthrates and aging population. The local products include short-horn beef, amber, sea urchins, abalone, and spinach. Traditionally, with 87 percent of the city lying in forested area, charcoal production has also been an important industry. The area’s mascot character is a female sea diver named “Amarin,” and she echoes the main character of a very popular 2013 NHK drama about a young woman from Tokyo who becomes a diver in Kuji City, Amachan. When we asked to be taught a bit of local dialect, we learned a phrase that became a nationwide hit due to its use in this drama; it’s an expression that mimics the feeling of surprise, je, and repeats it if the feeling is amplified into astonishment, jeje, or stupefaction, jejeje! In this leg of our journey, as well, we were introduced to local culture, but were not lectured on its preciousness or uniqueness.

Finally, what we experienced in Iwate is a domestic version of the Japan that can say “yes.” In this case, elite, central Japan is saying a very strong “yes” to its regional areas and cultures. By scheduling these Kakehashi Project study tours to all parts of Japan, the government is strongly asserting both the right and the duty of everyone in Japan to contribute to Japan’s joining the global scene, by incorporating some of those global stances at the individual level.

Students in front of the Meiji Shrine, Tokyo

Students in front of the Meiji Shrine, Tokyo

Since 2013, some 2,500 North American university students have been treated to Kakehashi Project study tours. In our case, we selected students who were studying Japanese but had never been to Japan. It was a great pleasure for us, and I am certain for them as well, to find that their Japanese language skills actually worked in Japan. It remains to be seen whether they will carry these new perspectives on Japan with them into the future. I am very glad, however, that the message of the tour was a mixed one, posing challenges and questions rather than answers for many of the issues of global concern.

Ann Wehmeyer is Associate Professor of Japanese and Linguistics at the University of Florida.