Kathy Curnow

Cleveland State University

k.curnow@csuohio.edu

Abstract

Rowland Abiodun’s Yorùbá Art and Language contains many extremely valuable features, wrapped around a question he raises in its introduction: can foreign scholars ever truly understand a work the way its Yorùbá makers and users do? Language mastery certainly provides the native speaker with access to inestimable insights regarding not only the general worldview but specifics of philosophy, history keeping, and subtleties of knowledge transmission. However, in the attempt to read an artwork and unpack its meaning, cultural insiders also face obstacles as well as advantages, particularly when pieces date from the more distant past. The import of Abiodun’s major contributions regarding Yorùbá art’s history and the validity of his contentions are considered here in light of the varied contributions both foreign and Yorùbá art historians bring to Yorùbá scholarship, in the recognition that working with art of bygone centuries makes all scholars outsiders to a degree.

A kì í gbójú-u fífò lé adìẹ àgàgà; à kì í gbójú-u yíyan lé alágẹmọ. One should not expect the flightless chicken to soar; one should not expect the chameleon to stride.

Can outsiders ever truly understand a work of art the way its makers and users do? In the introduction to his book Yorùbá Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art, Rowland Abiodun concludes that only those with a mastery of the Yorùbá language and deep cultural familiarity can interpret Yorùbá artworks effectively. His argument produces numerous salient observations and the viewing framework he creates provides an exceedingly valuable set of lenses for interpreting Yorùbá sculpture. However, the question posed above remains intriguing and is more complex than it appears. Even when an artist and his patron live in the same community at the same time, their interpretations of a commissioned work may not be identical, so when one moves out to the analyses of art historians, Yorùbá or not, one cannot necessarily assume a third party will understand the work just as its maker and user did. Additional corollaries to the question exist as well. What are the parameters of outsider status? Do they constitute a spectrum? Do insider advantages always trump outsiders’ perceptions? These issues become even more pertinent as the distance from our own era increases. While the question of outsider/insider status does not constitute the thrust of Abiodun’s book, it is a major aspect of his introduction, and thus worth considering.1

While this paper considers the unique multiple contributions of Abiodun’s book, it also argues that careful considerations of objects and context can be made by outsiders, while insiders, like all researchers, can choose to ignore elements that conflict with their own preconceptions, develop greater interest in one topic than another, generalize their known experience to the whole of Yorubaland or apply it half a millennium into the past. While these perspectives differ, one does not automatically eclipse the other.

Western Yoruba Scholars: Capable or Mired in Past Thinking?

Abiodun has been generous in his dialogues with many non-Yorùbá scholars, providing insights and suggestions through conversations about art and culture. He has also taught many students, American as well as Yorùbá, opening their eyes to new aspects of African art history. His collaborative relationships with Henry Drewal and John Pemberton, both non-Nigerian Yorùbá specialists are clearly mutually valued, and his book includes many positive citations of research by scholars who have adopted African frameworks of thought, such as a consideration of shared human and spiritual agency in art’s creation.2 His awareness that an African-oriented approach is not universal among Western discussions of African art led him to state: “I believe that negotiating artistic meaning and aesthetic concepts between two linguistically different cultures cannot be done only from an outsider’s language and point of view.”3

Abiodun’s evaluation of non-Yorùbá art historians splits the latter into two camps with an implied third. He notes some Western art historians refer to African art as “primitive,” “rarely venture outside of dominant Western paradigms, even when they analyze works from non-Western cultures” and judge Yorùbá sculpture by Western aesthetic standards.4 Fifty years ago this was true, but the scholarly world has changed considerably. Who are the scholars Abiodun refers to in these remarks? They seem to consist of: 1) non-Africanists, such as authors of “world art” textbooks who devote a sole chapter to all of African art, 2) Africanists who worked primarily from the 1950s to the early 1970s, when fieldwork was still minimal and anthropological methodology dominated, and—excluded from the misdeeds of the first and second groups, 3) Western Africanist art historians who bring contextual (and occasionally linguistic) abilities to their research. Abiodun does not discuss this third group at length, despite his own work with some of its members and their proliferation in recent decades.

In fact, Africanist art historians have long blasted the “primitive” moniker5 Abiodun rightly deplores and have also distanced themselves from past formalist-only approaches to African art.6 In accord with Abiodun’s convictions, the late Roy Sieber, who produced more Africanist art historians than any other professor,7 placed “primitive” on a classroom list of forbidden terms from at least the 1970s. As early as 1969, he critiqued anthropological scrutiny of objects in favor of multidisciplinary approaches to African art, stressing the importance of oral traditions and awareness of historical interaction and change. Sieber urged the consideration of works within a complex matrix of thought, underlining the acute importance of cultural relativism in African art studies–that is, discussion of art in terms of its makers’ viewpoints.8 Abiodun and Sieber would have agreed to the necessity of avoiding methodologies that place a low value on oral history and literature, as well as ontology. Those kinds of approaches should indeed be relics of the past.9

Insider/Outsider

Yorùbá historians of art have grown in number significantly over the past few decades. They include Abiodun himself, as well as Babatunde Lawal, dele jegede, the late Cornelius Adepegba, Moyo Okediji, Joseph Adande, Stephen Folaranmi, Bolaji Campbell, Yomi Ola, Pat Oyelola, Ola Oloidi, Kunle Filani, Daniel Olaniyan Babalola, Peju Layiwola (Yorùbá and Ẹdo), Aderonke Adesanya, Wahab Ademola Azeez, Babasehinde Ademuleya, P. S. O. Aremu, ‘deyemi Akande, and others. While being a native Yorùbá speaker does not intrinsically make one a better art historian, it is clearly an excellent tool for the researcher’s chest. However, not every Yorùbá speaker necessarily has equivalent exposure to and knowledge of some of the key resources for the deep understanding of objects. In-depth knowledge of Ifá divination verses, which reference many of the concepts necessary to perceptive interpretation of Yorùbá art, is not part of all Yorùbá scholars’ experience, nor are all native speakers familiar with other forms of oral literature relating to masquerade societies, ὸrìṣà worship, or hunters’ songs. Even if they have had exposure to these sources, not every speaker is intrinsically capable of extracting philosophical meaning from them. Many Yorùbá no longer reach adulthood having developed a familiarity with concepts that were more universal in the past, since lifestyle changes have accelerated in the last fifty years. What was once general cultural knowledge has often been supplanted, whether by Pentecostal treatises, textbooks on petroleum engineering, or code programming manuals. In 2002, an informal survey I conducted in Lagos with twenty Yorùbá males under the age of thirty revealed none who could name the ὸrìṣà of smallpox, none who knew of any masquerades other than egúngún, and none who had personally visited a diviner. None were headed to an academic career in art history, either, but the results suggested to me that once-common cultural knowledge is no longer automatically embedded, though it could clearly be learned.

Being Yorùbá certainly facilitates Yorùbá research. Language, ingrained sensitivity to required courtesies, contacts, and the possibility of long personal or family involvement with objects, religion, and performance are expeditious, and ease the establishment of new interpersonal relationships with culture brokers and investigative procedures. Might there be unique hindrances as well? For researchers, age, gender, “nationality” (whether foreign, or non-Yorùbá Nigerian, or Ìgbómìnà when conducting interviews in rural Ìlàjẹland), and personality all matter. Being an insider may or may not facilitate interaction. If you are an insider’s insider, a researcher working in your own home town, your entire family history colors your relationships with those you interview, as does your personal past. If you are Yorùbá, but work in a Yorùbá region other than your own, your status as stranger may raise suspicions of intent that must be–or may never be–allayed. Additionally, if your focus is on art of the distant past, might deep and broad cultural knowledge of the present create preconceptions that are difficult to shake off?

The foreign researcher faces a different set of issues. As Abiodun noted, friendship with cultural masters can be cultivated by Yorùbá and non- Yorùbá scholars alike10; it is the motivation of intellectual curiosity and one’s value for linguistic and historical insights that are imperative. Sometimes even the friendless stage of initial research, as well as initial ignorance, can work to a foreigner’s advantage in that they allow unrestricted pursuits. Some outsiders research over a sustained and lengthy period, developing deep relationships that develop into their absorption by extended foster families. This Yorùbá “adoption” certainly broadens their cultural understanding and can ease their research progress, but it has its own risks. One can all too easily inherit the enmities and alliances of family affiliates or face kindly-meant restrictions due to developed concerns about the researcher’s perceived vulnerability to supernatural or physical forces.

One of the greatest values outsiders can provide is a difference in perspective. Art historian Henry J. Drewal, for example, is fluent in Yorùbá. He conducted research in Yorùbáland over a period of many decades and covered a broader geographic territory than many Yorùbá art historians. His close collaborative relationships with Yorùbá scholars (including Abiodun), as well as with diviners, priests, Ògbóni Society members, and masquerade society officials certainly inform his thoughtful thoughtful work. Yet his foreign birth and education necessarily have generated some questions that differ from those of his Yorùbá colleagues, such as his interest in Yorùbá cosmetic tattooing, pursuit of diaspora visual connections in ὸrìṣà worship in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States, and Mami Wata worship among the Yoruba.11 Art historian Robert Farris Thompson, who has some facility with Yorùbá, conducted aesthetics-related interviews with Yorùbá artists and key patrons over an extended period of years. His results isolated a series of aesthetic criteria held by informed local viewers whose judgment did not always accord with that previously published by acknowledged Western specialists.12 Thompson additionally explored cross-cultural African aesthetics by eliciting critiques from members of one ethnic group of the art and performance of another, a fascinating and underrated effort13 that has not yet spawned additional Yorùbá scholarly investigations. These foreigners’ research priorities have taken different directions and the field is richer for these multiple interests.

Sometimes insiders and outsiders alike may value a foreigner’s research, even when it emerges from someone without deep roots, linguistic capability, or cultural familiarity. American photography professor Stephen Sprague, who, as far as I know, had minimal to no fluency in Yorùbá, stayed in Nigeria for a single summer. He became fascinated with how contemporary Yorùbá photo poses encoded cultural self-presentation, and his resultant article continues to resonate with Yorùbá and other Africanist scholars almost four decades later, 14 a testament to his fresh observations. Sprague’s discoveries inaugurated new lines of enquiry for Yorùbá researchers who developed his thoughts with their additional insights, demonstrating that observations by outsiders can trigger innovative thoughts or theories by insiders. Whether they are considered valid, as in Sprague’s case, or initially result in horrified reactions and counter-arguments, they can serve as catalysts.

New Contributions, New Terminology, Ifẹ Applications

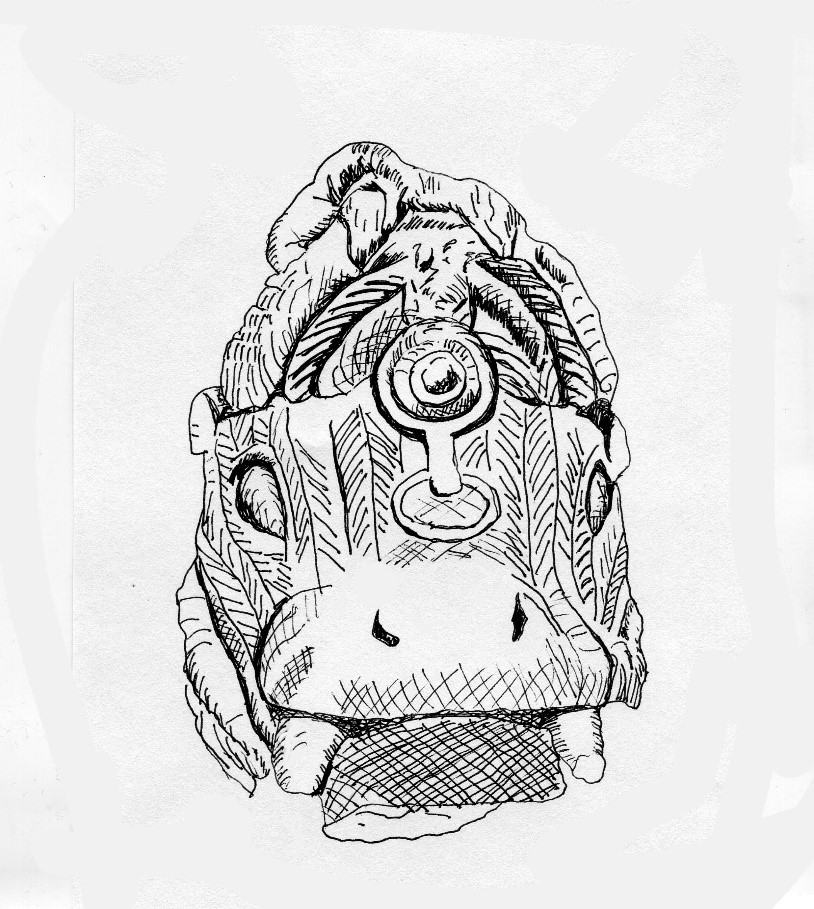

Certainly Abiodun is a highly-informed insider, and in Yorùbá Language and Art he takes object types well-established in the extensive literature about Yorùbá art, and spotlights critical aspects that had remained in the shadows. His chapter on orí inú (inner head) and its personal shrine, consisting of the ìbọrí within a leather ilé-orí container, was far from the first,15 but it includes and illuminates a salient fact previously absent. In a clear manifestation of the intimate relationship between Yorùbá art and language, the ìbọrí’s dedication incorporates sand. Before these granules became part of the shrine, they were spread out and inscribed with the line configuration that, in Ifá divination, marks a specific odù: the divination verse that references Orí (head) as an ὸrìṣà.16 It is the action of making these marks that is critical, as the marks themselves dissipate in the shrine’s construction, even as they empower it. Observations like this are revelatory and reinforce the power of invocatory words in Yorùbá creativity and practice. Abiodun’s discussions of shrine sculpture, equestrian figures, àkó effigies, and other topics in his book are equally rich.

His publication’s overarching contribution, however, may be the invention of three terms that are truly illuminating categorizations. They grow from deep linguistic and cultural reflection and have the ability to change the perspectives of those who employ them. All three terms are variations of the term àṣà, which might dryly be parsed as culture/tradition/custom, but which Abiodun embodies with additional concepts: creativity, style, innovation hand-in-hand with the established. The three terms are èpè-graphic àṣà, àṣe-graphic àṣà, and àkó-graphic àṣà, which he notes can overlap, and with their invention Abiodun has created a new lens for Yorùbá art history that has implications for future scholarship in other parts of the continent with analogous or other kinds of categories.

While his terminology can be applied to traditional17 Yorùbá art of any era, it is particularly helpful when applied to the more distant past, such as those terracottas and bronzes from 11th-15th century Ile-Ifẹ or to the early ivories and terracottas from Ọẁ ọ. While archaeology provides some valuable clues regarding these objects,18 it remains spotty in both areas. Until that situation shifts, many of our best insights emerge from internal evidence (the objects themselves) and oral literature. Abiodun uses both to make art speak.

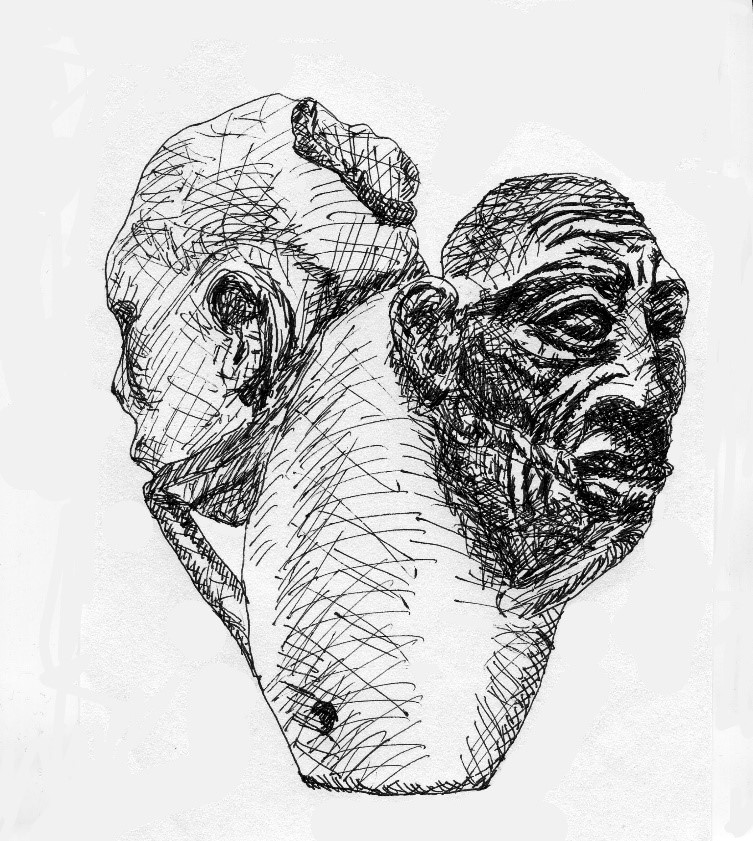

Èpè-graphic àṣà refer to curse-inflicting, punitive imagery, and Abiodun notes it is uncompromising in its literalness: generic physiognomy vanishes, as does all idealism. The identifiable targets include criminals, the diseased (not believed to be random victims), and those who are sacrificed for the greater good.19 This category is particularly useful in understanding those historical works which appear to break standard African art “rules” such as ephebism, as in this Ifẹ bronze (Fig. 1) that coexisted with many idealized human depictions.

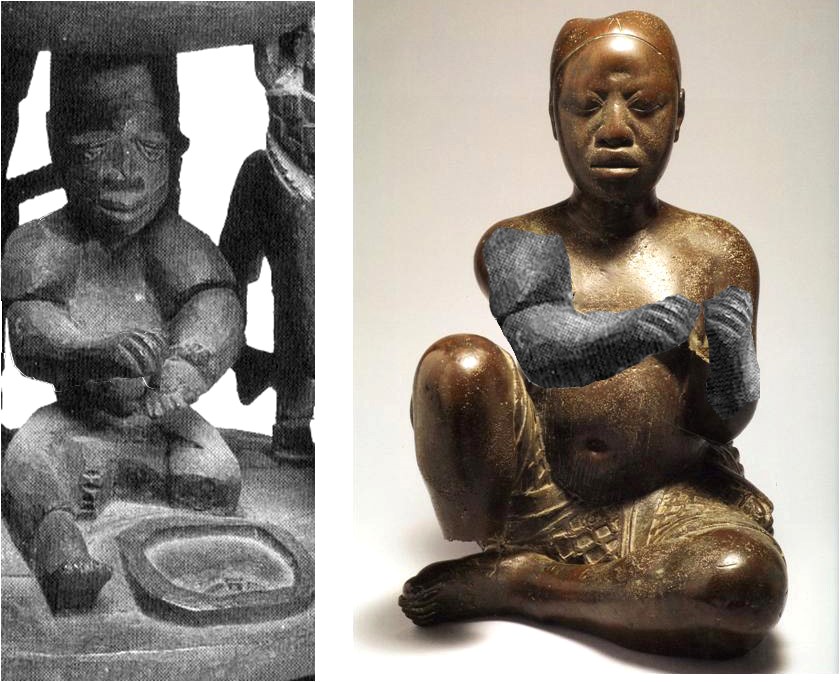

Ákó-graphic àṣà constitute idealistic representations of the deceased that laud their appearance and capabilities. This is, as Abiodun notes, the visual counterpart to an individual’s oríkì, a paean to dignity, self-restraint, and serenity. 20He attributes the bulk of the Ifẹ bronze heads and figures to this category, as well as the large cast Tada seated figure. This figure, which was still in use in a Nupe riverine village earlier in the 20th century, often is glossed over as simply an Ifẹ work found outside Ifẹ territory.21 However, even introductory- level students have speculated about its oddities within the Ifẹ corpus:

why are its head-to-body proportions natural, why is its pose more active than most contemporaneous works, and why is its dress (which Abiodun considersto be shorts, but might well represent a wrapper tucked through the legs and in at the waist) decidedly informal? Abiodun uses his ákó-graphic àṣà perspective to consider the figure, concluding it might well depict an Ifá priest in the act of divination (Fig. 2),22 an intriguing proposition. Àṣe-graphic àṣà seem to comprise the largest category of older Yorùbá art. Abiodun sees them as catalysts that recognize metaphysical rather than mimetic traits, with triggering capabilities for an individual’s àṣe, the animating force that makes things happen. As such, artists prioritize those parts of the body most associated with àṣe, employing disproportion that recognizes them as vital loci: oversized head, torso, hands, and feet. In works from Ifẹ, the aggrandizement of certain aspects of these features can clearly be seen in the two standing bronze male figures, the linked male/female bronze pair, the diminutive bronze representing a female figure wrapped around a pot

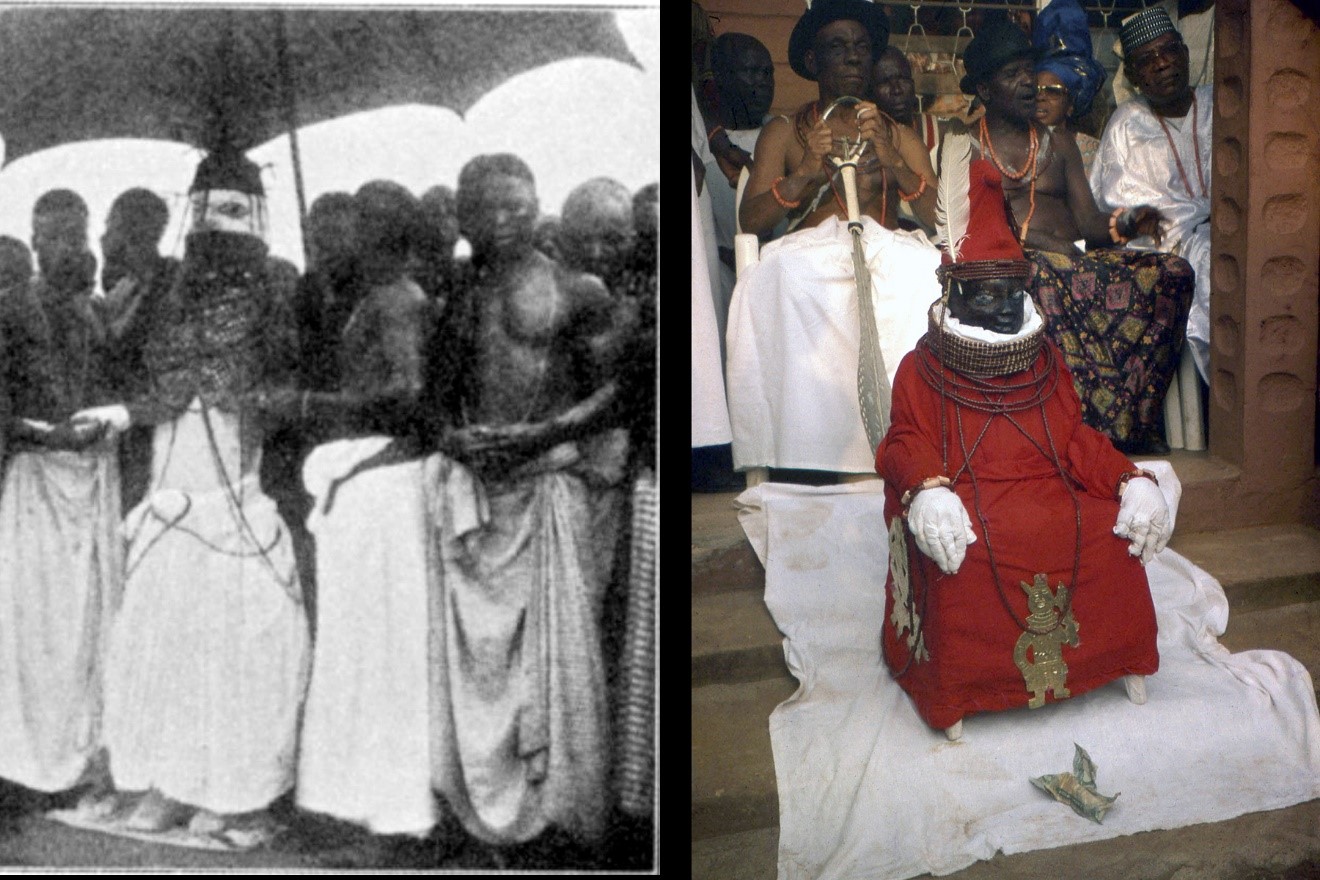

Like the àkó-graphic àṣà, these also visualize oríkì, but to different ends. While àkógraphic àṣà memorialize the deceased, àṣe-graphic àṣà are visual invocations that empower the living. When dealing with the past, we are all outsiders tiptoeing on potential quicksand. While oral literature and cultural knowledge are indispensable for interpretation of sites like Ifẹ and their objects (and it is to be hoped that Abiodun will look even more closely at the arts of historical Ifẹ, Ọwọ, and Ijẹbu in future), we must remain aware that backwards projections, even when they seem logical, remain hypotheses. Our oral histories and literature are not time-stamped, and many finds are accidental, having lost their communicative contexts. Before we assume our present knowledge is applicable, we should remind ourselves that human beings and their cultures inevitably change over time. At Ifẹ, the most obvious change regarding artworks is visual: style, which has abandoned the greater naturalism of the past for the more relative naturalism of the 20th century. We know from oral history of other cultural changes, such as female rulers. Although they have not been part of recent record, oral history has kept their memory alive. If we were solely to rely on living memory, both the actual appearance and context of Ifẹ art would be inconceivable. While Abiodun’s deep linguistic and cultural knowledge facilitate his art historical interpretations of works centuries old, these abilities cannot guarantee complete accuracy. Indeed, Ifẹ is an example of how present knowledge can impinge on the past. If in living memory àkó figures have never represented royals in Abiodun’s hometown of Ọwọ, must we assume that this could never have happened six hundred years ago at Ifẹ? Counter to Abiodun’s assertions, 24 similar figures (bearing the same name) that represent both the Ọba and his mother (Fig. 4) do make funerary appearances in the cognate culture of the Benin Kingdom to Ifẹ’s east. Likewise, Abiodun’s claim that, since representing the Ọọni would have been unthinkable as recently as the 19th century, Ifẹ bronzes could not have depicted the monarch, rests on an assumption that may or may not be valid. The former value of bronze, the siting of certain objects within former palace grounds at Ifẹ, and details of Ifẹ costume compared to early royal dress representations at Benin provide counter-evidence that some Ifẹ works, though certainly not all, may indeed represent both royal men and women. But is this really a problem? I believe it is instead an exhilarating, valuable aspect of scholarship. All of us who deal with older art are attempting the impossible: complete reconstruction of the Ifẹ contextual matrix in the 11th-15th centuries. That does not make attempts to place objects on an intellectual witness stand foolhardy, it just forces us to consider evidence of various kinds, thrash out our contentions in stimulating interchange, and discover what new archaeological finds might upend everything considered so far.

Coda

Ultimately, the principal value of Abiodun’s important book is his confirmation that Yorùbá art and language do not merely intersect. Many other Yorùbá and Yorùbáist art historians have quoted illustrative odὺ Ifá, oríkì, or other aspects of oral literature in their discussion of objects in enriching ways. Rather, what Abiodun demonstrates is that art and language walk such closely parallel paths that they reinforce one another like a doubled underscore. Each has an invocative goal that is less concerned with observation or reflection of nature than it is with action. Perhaps we scholars should view our own words as action-invokers. As both insider and outsider scholarship further considers art as a verb, and as collaboration, cordial argumentation, and varied perspectives increase, every tread will make the paths of art and language deeper and closer. These routes lead to fuller knowledge of Yorùbá art, and every step–by lightweight and heavyweight alike–establish them more firmly. If the chicken cannot fly, it still provides tasty nourishment; the chameleon’s lack of speed does not prevent its amazing transformative abilities, and outsiders’ interpretations need not be negligible if they value oral literature and histories, develop fresh questions, and remain in conversation with their Yorùbá colleagues to the benefit of the field.

Works cited

Abiodun, Rowland. “Understanding Yoruba Art and Aesthetics: The Concept of Ase.” African Arts 27.3 (1994): 68–78.

Abiodun, Rowland. Yorùbá Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Adeeko, Adeleke. “From Orality to Visuality: Panegyric and Photography in Contemporary Lagos, Nigeria.” Critical Inquiry 38.2 (2012): 330–361.

Blier, Suzanne Preston. “Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba.” African Arts 45.4 (2012): 70–85.

Blier, Suzanne Preston. Art and risk in ancient Yoruba: Ife history, power and identity, c. 1300. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Drewal, Henry J. “Art or accident: Yoruba body artists and their deity Ogun.” In Africa’s Ogun: Old World and New, ed. Sandra T. Barnes, pp. 235-260. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Drewal, Henry J. “Beauty and being: aesthetics and ontology in Yoruba body art.” In Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body, ed. Arnold Rubin, pp. 83-96. Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History, 1988.

Drewal, Henry J. “Mami Wata Shrines: Exotica and the Construction of Self.” In African material culture, ed. Mary Jo Arnoldi, Christraud M. Geary, and Kris L. Hardin, pp. 308-333. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Drewal, Henry J. and John Mason. Beads, Body and Soul: Art and Light in the Yorùbá Universe. Los Angeles, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1998.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson. “Projections from the Top in Yoruba Art.” African Arts 11.1 (1977): 43–49; 91–92.

Eyo, Ekpo. “Igbo ‘Laja, Owo.” West African Journal of Archaeology No. 6 (1976): 37–58.

Fagg, William. “The African Artist.” In Tradition and Creativity in Tribal Art, ed. Daniel Biebuyck, pp. 42–57.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1969. Fagg, William. Nigerian Images. London: Lund Humphries, 1963. Fatunsin, Antonia. “Recent Excavations at Owo.” Nigerian Heritage no. 1 (1992): 94–107.

Fraser, Douglas. “The fishlegged figure in Benin and Yoruba art.” In African Art and Leadership, ed. Douglas Fraser, pp. 261–294. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1972.

Gerbrands, Adrian A. “Review Primitive Art, Douglas Fraser.” American Anthropologist 65.5 (1963), 1184. Jones, Julie, Kate Ezra, Heidi King and Nina Capistrano. “Primitive Art.” Recent Acquisitions (Metropolitan Museum of Art) No. 1987/1988 (1987- 1988): 78–81.

Larsen, Lynne Ellsworth. CAA Reviews, June 9, 2016. http://www.caareviews. org/reviews/2703#.WsIqWIjwa70 Accessed June 14, 2017.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Àwòrán: Representing the Self and Its Metaphysical Other in Yoruba Art.” The Art Bulletin 83.3 (2001): 498–526.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Ori: The Significance of the Head in Yoruba Sculpture.” Journal of Anthropological Research 41.1 (1985): 91–103.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Orilonse: the hermeneutics of the head and hairstyles among the Yoruba.” In Hair in African art and culture, ed. Roy Sieber, pp. 92–109. New York: Museum for African Art; Munich: Prestel, 2000.

Sieber, Roy and Arnold Rubin, “On the Study of African Sculpture.” Art Journal 29.1 (1969): 24–31. Sprague, Stephen F. “Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves.” African Arts 12.1 (1978): 52–59; 107.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “An Aesthetic of the Cool.” African Arts 7.1 (1973): 40–43; 64–67; 89–91.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Esthetics in traditional Africa.” Art News 66.9 (1968): 44–45; 63–66.

Thompson, Robert Farris. African Art in Motion. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974.

Thompson, Black Gods and Kings. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1976.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Yoruba Art Criticism.” In The Traditional Artist in African Societies, ed. Warren D’Azevedo, pp. 19–61. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1973.

Willatt, Anna. “#girlbossesofgreatbritain–the one with the bootstrapping designer.” House of Coco blog, May 23, 2016.

https://www.houseofcoco.net girlbossesofgreatbritain-the-one-with-the-bootstrapping-designer/ Accessed February 23, 2017.

Willett, Frank with Barbara Blackmun. The Art of Ife: A Descriptive Catalogue and Database (CD-ROM). Glasgow: Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, 2004.

Footnotes

1 While some reviewers correctly noted that Abiodun points out a number of Africanist scholars whose work counters a wholly Western approach, others have also considered though not explored Abiodun’s observations in his introduction. Lynne Ellsworth Larsen’s positive review of the book, for example, states: “… I am wary of the implication that only those fluent in a particular language can offer insights into the art of a particular culture” (CAA Reviews, June 9, 2016)

2 Rowland Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art(New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 16.

3 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art (2014), 16.

4 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art (2014),1; 8–9.

5 “Primitive” was once rife in exhibition and book titles. Some museum departments bore it, such as the Art Institute of Chicago (at least as late as 1968), and terminology shifts were gradual. Although the Metropolitan Museum of Art absorbed the earlier Museum of Primitive Art in 1974, opening its collection in 1982 as the “Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas” wing, the museum’s publications continued to use the label “primitive” well into the late 1980s (Julie Jones, Kate Ezra, Heidi King and Nina Capistrano. “Primitive Art,” Recent Acquisitions [Metropolitan Museum of Art] No. 1987/1988 [1987-1988]: 78–81). Numerous auction houses, dealers, and collectors still cling to the term, in contrast to scholars.

6 Abiodun accurately notes that the Modernists’ adoption of African forms without consideration of their content perpetuated a formalist approach to African sculpture (“Understanding Yorùbá Art and Aesthetics: The Concept of Ase,” African Arts 27.3 [1994]: 69). While this approach persists among some dealers and collectors, it dominates few Africanist scholar’s work today. Stylistic analysis in concert with context can be useful, revealing temporal and geographic spheres of interchange, as ère ìbejì surveys have demonstrated.

7 In the interest of transparency, the author was one of Sieber’s students at Indiana University. At this same university, the author’s year-long study of Yorùbá and lack of tonal mastery generated mirth among her teacher and his friends whenever, for example she attempted to pronounce the Yorùbá word for “farm”. Due to her own linguistic incompetence, the author hereby apologizes for any orthographic inconsistencies, as well as any misuse of diacriticals or their absence in proper names.

8 Roy Sieber and Arnold Rubin, “On the Study of African Sculpture,” Art Journal 29.1 (1969): 24–31. This essay, reworked from their 1968 Tishman catalogue, was the first by Africanists in a professional art history periodical, reaching a large audience in the broader discipline.

9 They were common in earlier decades of the discipline. The late Douglas Fraser, for example, attributed the origin of a Yorùbá and Ẹdo motif to the ancient Middle East, without thorough consideration of its contextual meaning (“The fish-legged figure in Benin and Yoruba art,” in African Art and Leadership, ed. Douglas Fraser, pp. 261–294 [Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1972]). Fraser’s diffusionism did not go unchallenged, however, even at the time. Dutch anthropologist Adrian Gerbrands skewered what he termed Fraser’s “matters of faith” in terms of unproven historical relationships based on imagery alone, noting “the farther away [from the present] the more exciting, as the author puts it” (“Review Primitive Art, Douglas Fraser,” American Anthropologist 65.5 [1963], 1184).

10 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014), 7, passim.

11 Henry J. Drewal’s explorations of Yorùbá tattooing can be found in “Beauty and being: aesthetics and ontology in Yoruba body art” in Marks of Civilization: Artistic Transformations of the Human Body, ed. Arnold Rubin, pp. 83-96 (Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History, 1988) and “Art or accident: Yoruba body artists and their deity Ogun” in Africa’s Ogun: Old World and New, ed. Sandra T. Barnes, pp. 235-260 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989). His work on diaspora connections culminated in his exhibition catalogue with John Mason, Beads, Body and Soul: Art and Light in the Yorùbá Universe (Los Angeles, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1998), and the Yoruba facet of his Mami Wata publications is a particular focus of “Mami Wata Shrines: Exotica and the Construction of Self” in African material culture, ed. Mary Jo Arnoldi, Christraud M. Geary, and Kris L. Hardin, pp. 308-333 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996).

12 Robert Farris Thompson’s most comprehensive aesthetics study is found in “Yoruba Art Criticism” in The Traditional Artist in African Societies, ed. Warren D’Azevedo, pp. 19–61 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1973), but he reexamined aesthetics more broadly in both “An Aesthetic of the Cool,” African Arts 7.1 (1973): 40–43; 64–67; 89–91 and “Esthetics in traditional Africa,” Art News 66.9 (1968): 44–45; 63–66. Thompson’s observed criteria of straightness and symmetry, which he elsewhere called gigun (Black Gods and Kings [Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976], 3/2), countered William Fagg’s earlier interest in the artist Fagg called the “Master of Uneven Eyes” (“The African Artist,” in Tradition and Creativity in Tribal Art, ed. Daniel Biebuyck, pp. 42–57 [Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1969], 50). The crookedness of that artist’s carved eyes, which Fagg found compelling, would have disqualified him as a fully competent artist in the Yorùbá aesthetic framework Thompson described.

13 Robert Farris Thompson, African Art in Motion (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974).

14 References to Stephen F. Sprague’s article (“Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves,” African Arts 12.1 [1978]: 52–59; 107) have been made by Abiodun himself (Yorùbá Art and Language [2014], 183, 197, 200–202), as well as by Babatunde Lawal (“Àwòrán: Representing the Self and Its Metaphysical Other in Yorùbá Art,” The Art Bulletin 83.3 [2001]: 498–526) and humanities scholar Adeleke Adeeko (“From Orality to Visuality: Panegyric and Photography in Contemporary Lagos, Nigeria,” Critical Inquiry 38.2 [2012]: 330–361), as well as other researchers. In addition, the article’s reach transcends academia; London-based Yorùbá designer Elizabeth-Yemi Akingbade of Yemzi cites it as inspiration for her recent fashion collection (Anna Willatt, “House of Coco” blog, May 23, 2016). One could argue that Sprague’s access to Yorùbáist art historian Marilyn Houlberg provided a cultural knowledge shortcut, but his own training and familiarity with studio portraits prompted his inquiries.

15 Other authors who have commented on the topic of ìbọrí at length include Robert Farris Thompson (Black Gods and Kings [1976]), Margaret Thompson Drewal (“Projections from the Top in Yoruba Art,” African Arts 11.1 [1977]: 43–49; 91–92), and Babatunde Lawal (“Ori: The Significance of the Head in Yoruba Sculpture,” Journal of Anthropological Research 41.1 [1985]: 91–103 and “Orilonse: the hermeneutics of the head and hairstyles among the Yoruba” in Hair in African art and culture, ed. Roy Sieber, pp. 92–109 [New York: Museum for African Art; Munich: Prestel, 2000], as well as “Àwòrán: Representing the Self and Its Metaphysical Other in Yoruba Art,” The Art Bulletin 83.3 [2001]: 498–526). Abiodun’s observations added a new level to this previous scholarship.

16 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014), 33–34.

17 Academics have attacked the terms “traditional” and “contemporary,” since artworks described with these words can be contemporaneous, and the two divisions do not constitute closed circles in opposition. However, no concise descriptors have yet replaced them, so I use them with those caveats.

18 The most comprehensive Ifẹ site listings and images can be found in Frank Willett with Barbara Blackmun, The Art of Ife: A Descriptive Catalogue and Database [CD-ROM] (Glasgow: Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, 2004). Only Blackmun’s contribution, however, includes interpretation of the finds. Ọwọ archaeological work was conducted by Ekpo Eyo (“Igbo ‘Laja, Owo,” West African Journal of Archaeology No. 6 [1976]: 37–58) and Antonia Fatunsin (“Recent Excavations at Owo,” Nigerian Heritage no. 1 [1992]: 94– 107). Exciting work on Ifẹ glass by archaeologists and scientists such as Akin Ogundiran Lasisi Olanrewaju, Tunde Babalola, Akin Ige, and others expands our knowledge of the past, but does not rely on oral tradition.

19 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014), 241–43.

20 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014): 226–235.

21 Fagg speculated the figure originally sat on an actual quartz throne (Nigerian Images [London: Lund Humphries, 1963], 16), and Suzanne Blier suggested its missing forearms might have been posed in the Ògbóni members’ hand-enclosing-thumb gesture (“Art in Ancient Ife, Birthplace of the Yoruba,” African Arts 45.4 [2012]: 73 and Art and risk in ancient Yoruba: Ife history, power and identity, c. 1300 [New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015], Plate 4; 53).

22 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014): 229–234.

23 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014): 336–340.

24 Abiodun, Yorùbá Art and Language (2014): 184-85; 210; 226 for àkó and monarchs generally, and 107–9; 216–220; 226; 236–37 for Ifẹ bronzes.