Forget what you learned in history class and imagine, for a moment, that the founding of the United States does not begin with Jamestown Colony or the Pilgrims.

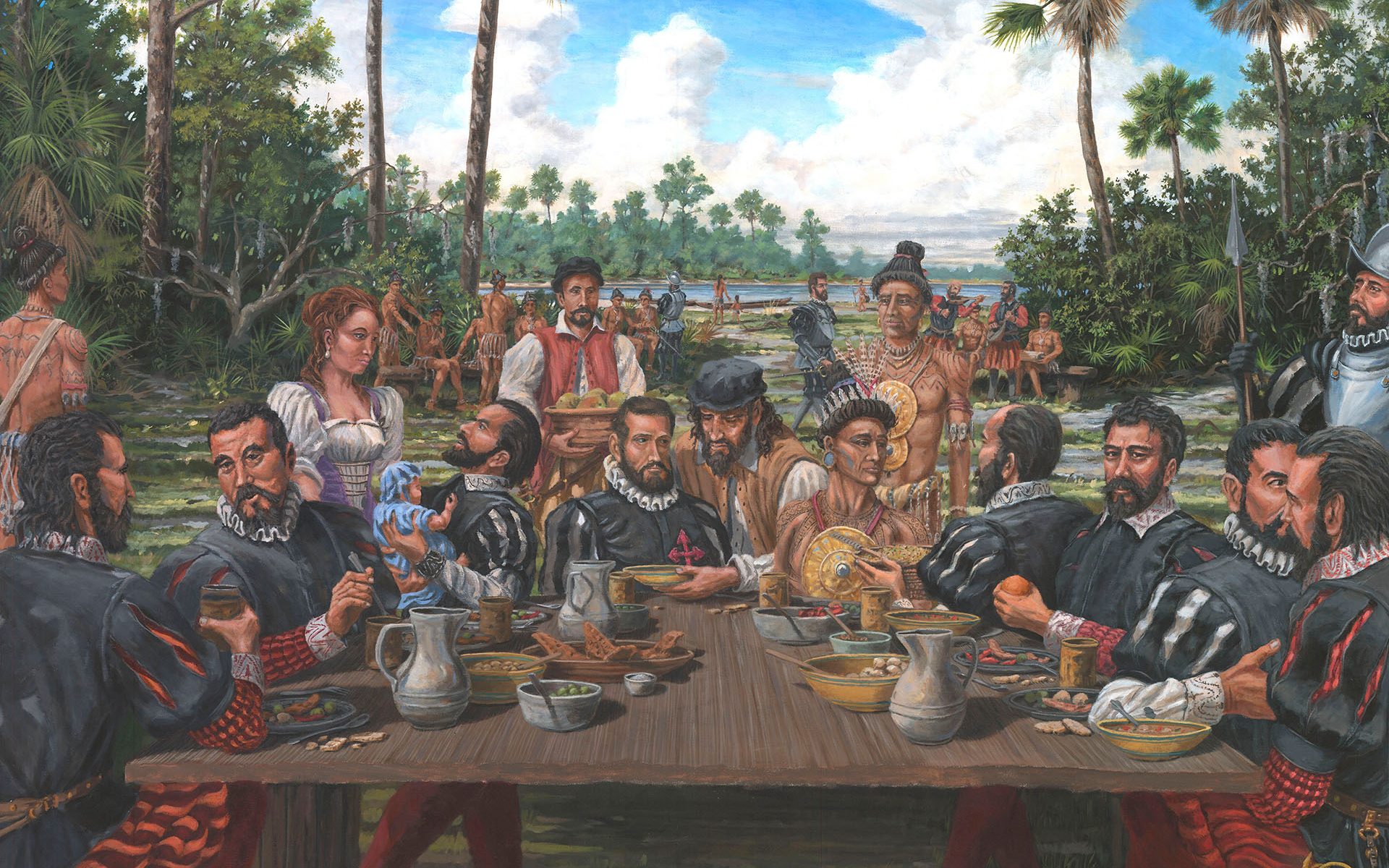

Our nation’s first permanent settlers are not the British pioneers who built a fort on the James River in 1607 but, rather, a melting pot of Spanish, German, French, English, and African homesteaders who stake their claim more than 40 years earlier — on Sept. 8, 1565 — on Florida’s turbulent Atlantic coast. Their leader, an intrepid Spanish admiral and fervent Catholic, names the new colony after a North African saint, befriends the local indigenous people, and celebrates the rst mass in the Americas. To top things off, the grateful admiral orders that a Thanksgiving meal of salted pork and garbanzo beans be prepared for everyone, colonists and natives alike — all more than half a century before the Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock.

Sounds a bit far-fetched. Except it’s not: It’s the actual, evidence-based history of the founding of San Agustín (St. Augustine), Fla., as painstakingly researched by experts from the University of Florida and other leading institutions. And this research is at the heart of an engrossing new documentary, The Secrets of Spanish Florida, which first aired on PBS in December 2017. Dedicated to the memory of renowned Florida historian, UF’s Michael Gannon (1927– 2017), the two-hour film tells the story of America’s past “that never made it into textbooks” and is sparking new discussion about the cultural, racial, and religious diversity that has been at the heart of the American experience for nearly 500 years.

Our nation’s history “is multicultural from day one,” says University of Central Florida historian Rosalyn Howard, pointing to early St. Augustine. “If we took that as a beginning, I think we would have a very different picture of the United States.”

The Secrets of Spanish Florida gets down and dirty with history as it follows archeologists, marine scientists, and historians on a quest to uncover this forgotten side of America’s origins. As the camera pans in on the Fountain of Youth Archeological Park, just north of St. Augustine, we see professor Kathleen Deagan and a team of UF archeologists unearthing artifacts that have lain buried for more than four hundred years: musket balls, uniform buttons, and orange- and-blue glass beads. To the uninitiated, these mundane objects may not seem like treasures, but to Deagan, one of the nation’s leading Spanish colonial archeologists, their long-awaited discovery is the researcher’s equivalent of a “smoking gun”: tantalizing evidence of where Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (1519–74) likely first settled with his colonists when they came ashore in 1565.

“It’s the first place in the United States that Europeans came and stayed,” says Deagan, underlining the site’s significance.

And there is evidence of the children who came with these first settlers. Researchers found a figa amulet, an object in the shape of a clenched fist, which Spanish mothers hung around their babies’ necks to ward off the evil eye. “We just couldn’t help imagining this was associated with Martín de Argüelles, the first European child born in what is now the United States,” says Deagan.

Records from 16th-century Saint Augustine reveal another astonishing fact: About a quarter of marriages then were between Spaniards and native Americans. In fact, for 234 years, people of different races, ethnicities, and religions lived side by side in relative peace in this city.

Elsewhere in St. Augustine, UF researchers have discovered the science behind the enduring power of the Castillo de San Marcos, the vast seaward-looking fortress built to ward off British raiders like Sir Francis Drake. How was it able to withstand enemy bombardments of more than fifty days when other forts blew to bits? Its walls were made of coquina, a soft limestone of broken shells, which absorbed the cannonballs’ impact rather than shattered. Ghatu Subhash, the UF researcher in material sciences who solved this mystery, dispels any illusions viewers might have of the original builders’ brilliance in choosing this new technology:

“They just got lucky,” Subhash says with a smile.

In addition to showcasing the forensic and analytical work of these and other UF experts such as historians Jack Davis, Eugene Lyon, Jane Landers, and James Cusick, The Secrets of Spanish Florida features vivid reenactments of little-known events in Spanish Florida history. We see African slaves from British-owned plantations escape on a “reverse” Underground Railroad that takes them south to Spanish Florida, where they are given freedom in exchange for allegiance to the Spanish Crown and the Catholic faith. We applaud as former slave Francisco Menéndez leads his people to found the first free black colony in the United States in 1738, nearly 125 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. And there is the poignant scene of the entire population of St. Augustine — more than 3,000 people — abandoning their city to set sail for Havana, Cuba, a year after Spain cedes La Florida to the British in 1763.

Most of these events have been written out of the official historical narrative of our country.

Not surprisingly, The Secrets of Spanish Florida has generated considerable buzz. The documentary reached more than 3.7 million viewers when it aired on Dec. 26, 2017 and has generated more than 60,000 digital streams on the PBS website. Viewer comments attest to the program’s power to move and to challenge our notions of how our nation began: “It’s humbling to realize the extent to which the victors’ [England’s] version of history has kept the full story from us and interfered with our ability to learn from that past,” writes a fan from Massachusetts. Elsewhere, commenters spar about events left out of the film and possible errors or misinterpretations of facts.

But such heated reactions are to be expected when we are asked to reconsider our long-cherished stories of national identity, including that holy of holies, the origins of Turkey Day. A few years ago, UF historian Michael Gannon drew fire when he called Pedro Menéndez’s Sept. 8, 1565, feast “the true first Thanksgiving.” In the beginning of The Secrets of Spanish Florida, he explains what happened next:

“There was a guy who called me from WBZ, in Boston. He said, ‘While I’m talking, do you realize there is an emergency meeting of selectmen at Plymouth to contend with this new information that there were Spaniards in Florida before there were Englishmen in Massachusetts?’ And then he said, ‘Well, you know how you’ve become known up here in New England?’ I said no. He said, ‘The Grinch Who Stole Thanksgiving.’”