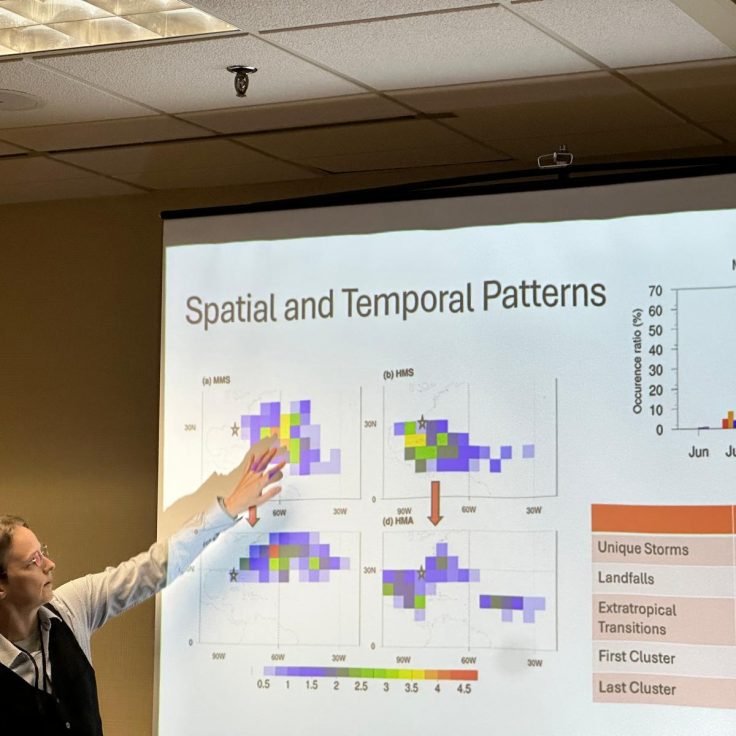

Tinaja kiln in the valley of Moquegua, with UF professor Susan deFrance pictured on the right. Photo by Prudence Rice.

Unearthing Real-Life Indiana Jones Moments

Three UF archaeologists share their thrilling adventures

As the latest Indiana Jones film, “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny,” captivates audiences worldwide, University of Florida archaeologists understand first-hand that their work goes far beyond the glitz and glamour of Hollywood. Still, Jones’ thrilling quests for discovery on the big screen sometimes aren’t too far off from the realities that come along with the chosen career path.

While archaeologists welcome the heightened public interest in their field thanks to the Indiana Jones series, they also acknowledge the fictional nature of his character. Ken Sassaman, the Hyatt and Cici Brown Professor of Florida Archaeology, highlights this duality.

“On the one hand, we all appreciate the greater public awareness for archaeology,” he said. “But on the other hand, the persona and storylines are not actually about archaeology, at least not what we actually do.” Unlike the character, Sassaman explains, the real focus isn’t on acquiring objects, but rather extracting valuable information. The modern approach does not involve collecting or appropriating them.

While real-life archaeology may not always match the thrill of movie adventures, researchers have plenty of captivating stories to share — even if they may not involve knife fights with villainous foes, discovering extraterrestrial civilizations, or dodging rolling boulders in ancient tombs. Our esteemed faculty members have their own remarkable tales from the field to recount that showcase the excitement and intrigue found in the world of archeology.

The River Rapids Rescue

Augusto Oyuela-Caycedo, associate professor of anthropology, hails from Colombia. He embarked on his archaeological career after obtaining a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology at the Universidad de Los Andes in Bogotá. His early adventures would have made Indiana Jones himself proud. Oyuela-Caycedo has hitched a boat ride with poachers in a medical emergency, escaped giant, deadly constrictors in remote areas, and even faced a gun threat for accidentally stumbling upon an illegal marijuana field while conducting pottery surveys.

One of Oyuela-Caycedo’s most harrowing experiences unfolded while he was exploring the Colombian Amazon. As part of a team comprising local researchers and guides, he sought evidence of early humans in the treacherous and isolated region. Accessing the research camp proved challenging, requiring a small plane that would tragically crash on a separate expedition that Oyuela-Caycedo was not involved in. Once at the base camp, reaching the research sites entailed arduous hikes through the jungle and navigating raging rapids in a small canoe.

During one such excursion, after braving the rapids and a full day of hiking, one of Oyuela-Caycedo’s local research assistants approached him with a serious injury: a venomous snake had bitten him on the back of the leg, and he would require medical attention to survive. Fortunately, there was a medic available at the base camp, but reaching them would require retracing their steps and returning by boat, which would take a full day. While his assistant managed to board the boat, the pain grew increasingly intense during the ride and his skin started to necrose. Oyuela-Caycedo knew that he had to take immediate action. They had brought with them two small vials of antivenom as a precaution, but circumstances forced them to administer it in the middle of the river, in choppy waters, amidst the darkness of night.

“It’s one thing to administer antidote in the wilderness, but trying to do it in those conditions was not easy,” Oyuela-Caycedo said. “It’s a rather precise procedure, filling the needle with the correct dosage and making sure to get all of the oxygen out of the needle before injecting. Now try doing all of that in the dark, in the rain, and on a rocking boat.”

Eventually, Oyuela-Caycedo managed to successfully administer the antivenom to the assistant, at which point he stopped crying out and subsequently passed out in the boat. Thanks to Oyuela-Caycedo’s swift intervention, the assistant survived the ordeal.

The Lost Head

Professor Susan Gillespie is renowned for her expertise in the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica, including the Mayans, Aztecs, and Olmecs. Prior to joining UF faculty in 2001, she was a field researcher. One notable investigation she conducted back in 1991, alongside her late husband, David C. Grove, delved into the Olmecs in Veracruz state, situated on the Gulf Coast of Mexico.

The Olmecs, considered Mexico’s oldest known civilization, inhabited the Veracruz region from approximately 1200 to 500 BC. They are perhaps best known for their art, such as jade masks, mosaics, and most famously, colossal head statues. These colossal heads have captivated archaeologists not only due to their impressive size but also the remarkable efforts required to transport and position them along the coastal areas.

“There is no stone to be found along that coastal plain,” Gillespie said. “This means they had to drag huge basalt boulders from the Tuxtla Mountain range some 100 miles away.”

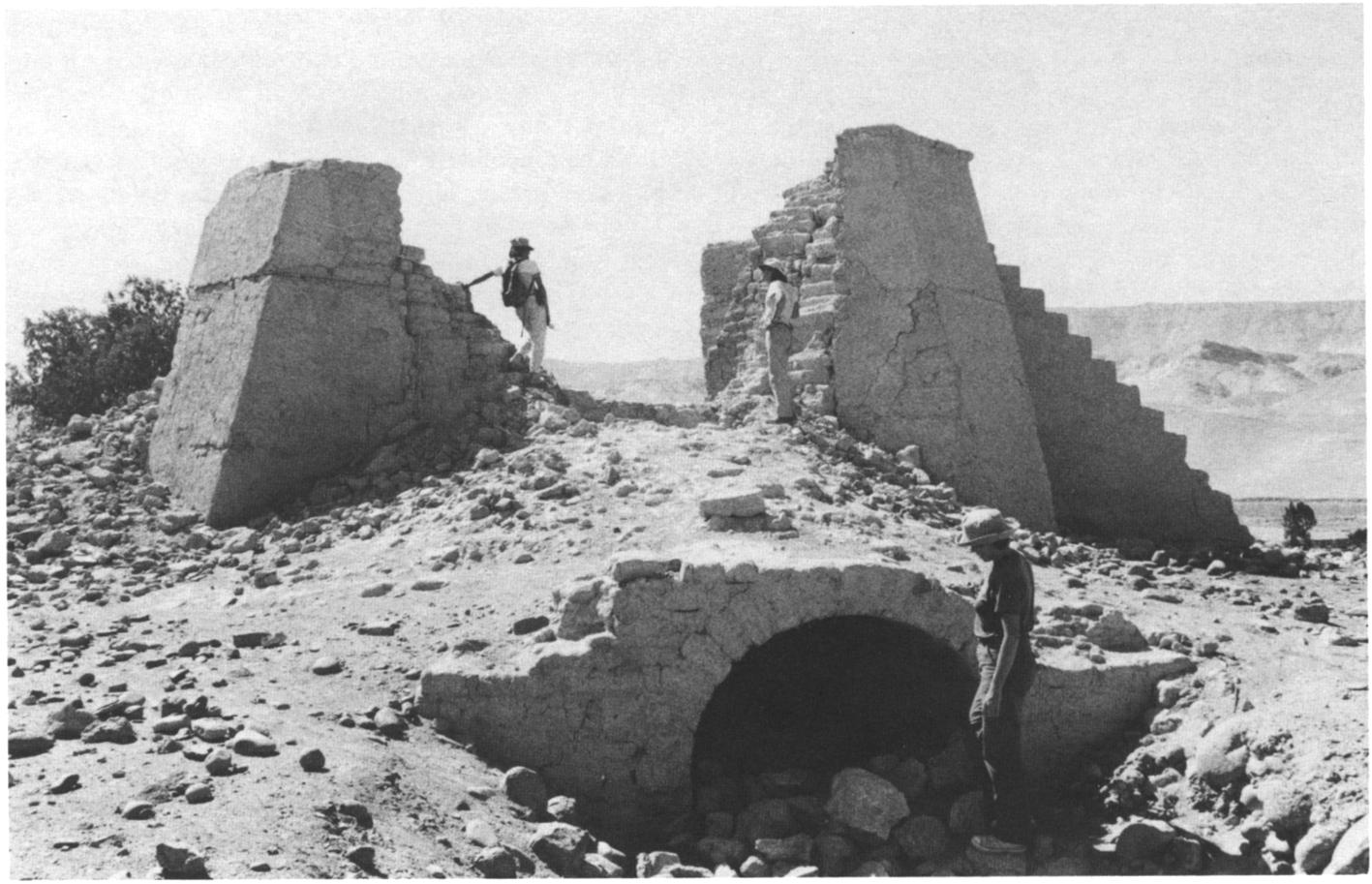

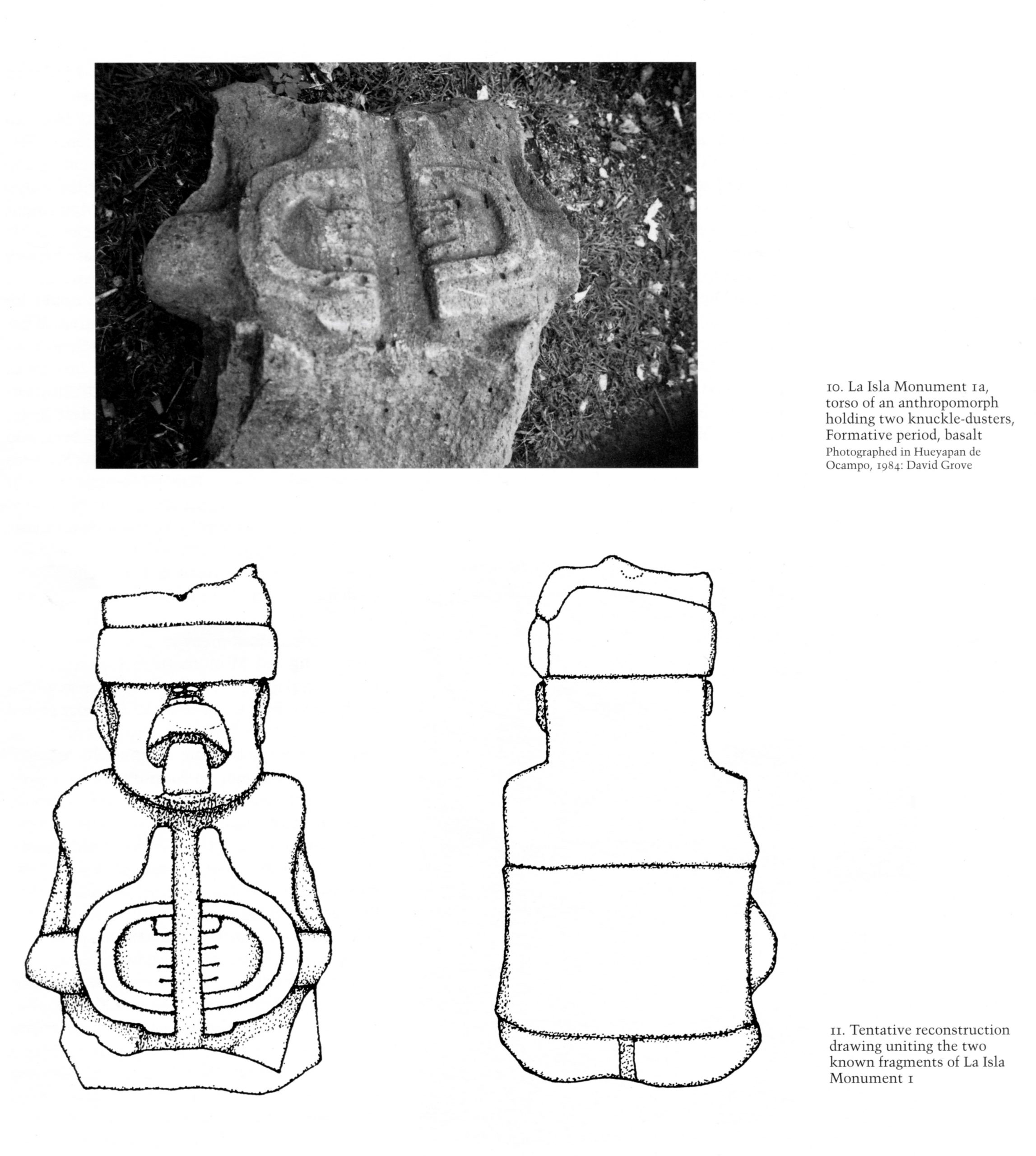

Their investigation into how the statues were made brought Gillespie and her team to the foothills of the Tuxtla Mountains. In the municipality of Hueyapan de Ocampo, she and Grove had earlier seen statue fragments placed outside the municipal offices. One was an intact head, while another was just a torso devoid of arms, legs, or a head.

Seven years later, Gillespie returned to the area to continue her search for other statues and statue fragments. Their efforts led to some new discoveries, but not every lead they followed yielded fruit. Some leads took them to mundane objects like an old grindstone, a naturally eroded rock, and a prized head statue kept in a jail cell that turned out to be a recent carving.

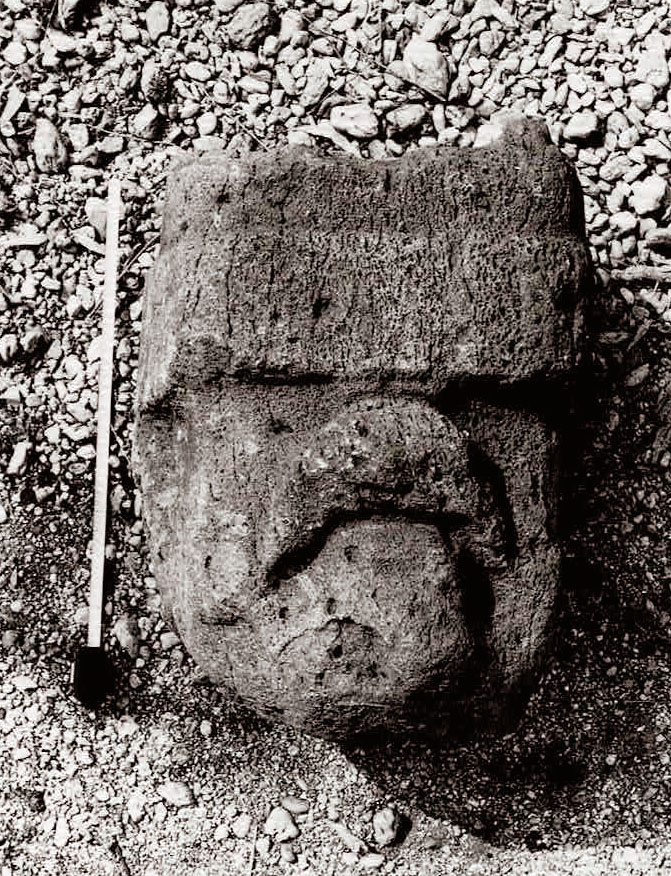

After weeks of chasing leads, the owner of the property where Gillespie and her team were residing casually mentioned that her brother-in-law had a stone in his backyard. After so many disappointing leads, Gillespie was reluctant to chase another, but agreed to investigate regardless. At first glance, the stone looked rather ordinary, but when Gillespie turned it over, she realized that it was a statue, or at least part of one.

“Something leaped out at me,” Gillespie said, “and I exclaimed ‘¡Es una cabeza!’ ‘It’s a head!’”

Bottom: A sketch of what the head and body would look like when put together.

Photos courtesy of Susan Gillespie.

Curious about how the head had come to rest there, they asked the landlady, who explained that someone had found it toppled over in a stream at a site known as La Isla, the same place where the torso had been found.

At that point, the torso had been moved from the municipal offices to the state Museum of Anthropology in the capital. To ascertain if the two pieces could be united, Gillespie took measurements of the head and made sure to visit the museum on the way back to the US to see the torso.

“To our delight,” Gillespie shared, “the torso matched perfectly with the head in Hueyapan de Ocampo.”

Tombs and Wineries

Susan deFrance, a professor of anthropology, was an undergraduate student and field researcher at Louisiana State University when “Raiders of the Lost Ark” first hit theaters in 1981. She remembers getting a laugh out of the movie’s bombastic, over-the-top portrayal of her field of work, and after seeing the film, she soon resumed her excavations of Poverty Point, Louisiana.

“We were digging around in the 95-degree heat looking for fired clay objects and simple stone tools,” deFrance said. “We were finding interesting things, but we certainly weren’t finding the Ark of the Covenant!”

Over the course of her career, deFrance has braved elements that would deter even the fearless Indy. As a graduate student at UF, she traveled to Peru for her dissertation research, conducting research despite earthquakes, volcanoes, and El Niño floods.

Her journey led her to the valley of Moquegua, where her team investigated the well-preserved ruins of Spanish colonial wineries. Among their discoveries were large ceramic vessels used for storing the wine, called tinajas.

However, these well-preserved vessels were not the team’s most significant find. Thanks to a coating of volcanic ash in the wineries, the team could approximate a rough age for the winery, by dating the ash back to an eruption of the Huatnaputina volcano in February 1600.

Later in her career, deFrance was a part of the team that excavated Tacahuay Tambo, an Incan site on the Peruvian coast. In doing so, they found a large family tomb, complete with ceramics and other artifacts buried with the family.

“Oftentimes, people visiting sites ask: ‘what have you found,’” deFrance said. “We like to remind people that archaeology is not about what you find, contrary to Indiana’s adventures, but what you find out.”