Turtle Tracker

In the U.S. Virgin Islands, a critically endangered species’ population has rebounded, but threats — and questions — remain

The origin of the hawksbill turtle’s name is no mystery: The reptile has a narrow, beaklike mouth that, coupled with a powerful jaw, allows it to pry sponges and coral from the nooks and crannies of reefs that comprise its foraging habitats. The turtle’s namesake feature, though, isn’t even its most distinctive.

Across its shell blazes a striking sequence of intermingling gold and brown bursts. The resulting display is the source of — or, more often these days, the inspiration for — the “tortoiseshell” pattern found on glasses frames, combs, jewelry and other products. The eye-catching array has made the hawksbill turtle a prime target for poaching, a leading factor in the severe population declines globally that have left the species critically endangered today.

At Buck Island Reef National Monument near St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, though, the story has thankfully changed. Because of a widescale effort by the National Park Service begun in 1988 to eradicate invasive predators and deter poaching, the number of hawksbill turtles showing up on the shores of this small, uninhabited island has drastically increased. Last summer, it was up to University of Florida turtle researcher ALEXANDRA GULICK to find out the extent of the rebound. Along the way, she discovered that there’s still more work to be done.

Gulick, who received her PhD in zoology at UF earlier this year, was a natural fit for the job. Now a postdoctoral researcher at UF’s Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, Gulick first discovered her passion for sea turtles during an internship at Buck Island Reef National Monument in 2013. After starting graduate school, she returned often to study the monument’s foraging areas for her doctoral dissertation on green sea turtle grazing dynamics in seagrass meadows with the Archie Carr Center.

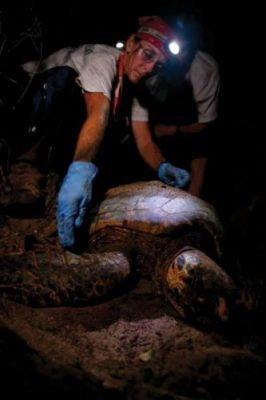

The National Park Service (NPS) selected Gulick as a 2021 Scientists in Parks Fellow and tasked her with analyzing the data the agency had amassed on Buck Island’s hawksbill turtle population. Gulick had her work cut out for her. The hawksbill bounce- back had been monitored through decades of meticulous tracking and tagging by the NPS, producing a massive data set.

“They encounter 99% of females that come up onto the beach during peak nesting season. That’s no small task,” Gulick said. “NPS biologists and interns are out there walking the beach every night for months at a time.”

In an open access paper, Gulick and NPS co-authors found that the hawksbill nesting population at Buck Island has grown from about 12 females encountered in 1988 to about 60 to 80 in recent years, for an estimated 500 females total in the population. (Not all of them nest yearly, and it takes 30 years for turtles to reach maturity.)

The full picture is more complicated, however. The nesting population at Buck Island over the last 13 years has plateaued. Gulick also found that the body size of the nesting females has significantly declined over the last few decades, as has the number of eggs laid per nest — further indications that the future for these turtles isn’t necessarily secure. One possible culprit: climate change.

Warming temperatures, sea level rise and increased storm frequency can stress the coral reefs that hawksbills rely on for food and habitat, Gulick said. With fewer resources available, the females don’t grow as quickly or become large enough to produce as many eggs as previous generations. Climate change could also lead to an out-of-balance turtle population: Hawksbills’ sex is determined in the embryo by the temperature of the nest, and warmer temperatures result in more females.

Other factors are likely at play. The stagnant population at Buck Island could mean that many turtles are now nesting more frequently on the nearby island of St. Croix, which is populated by humans, and many of its beaches are unprotected and unmonitored. Part of Gulick’s fellowship involved conducting community outreach workshops on St. Croix about turtle nest monitoring and conservation.

“It gets the public involved and invested in turtles,” she said. “These efforts help give them the tools they need to understand what they’re seeing on local beaches.”

Gulick’s analysis is a starting point for future researchers to untangle what exactly is causing the changes in the hawksbill population. But as she and others look to the future, Gulick is mindful not to take for granted the remarkable work by the many NPS biologists, interns, visiting scientists, and community members that have contributed to the monitoring program. In particular, she is inspired by Zandy Hillis-Starr, the recently retired NPS Chief of Resource Management at Buck Island who spearheaded the remarkably successful conservation effort.

“So many students and biologists like me have gotten to experience the park and learn from her,” Gulick said. “Her work is a major reason why park visitors can still experience hawksbill turtles today.

Learn more about the success of the program by reading Gulick and her co-authors’ full study here.

This story appears in the fall 2022 issue of Ytori magazine. Read more from the issue.