Hearing Their Voices

The English Language Institute helps foreign students adapt to their new environment

By Barbara Drake

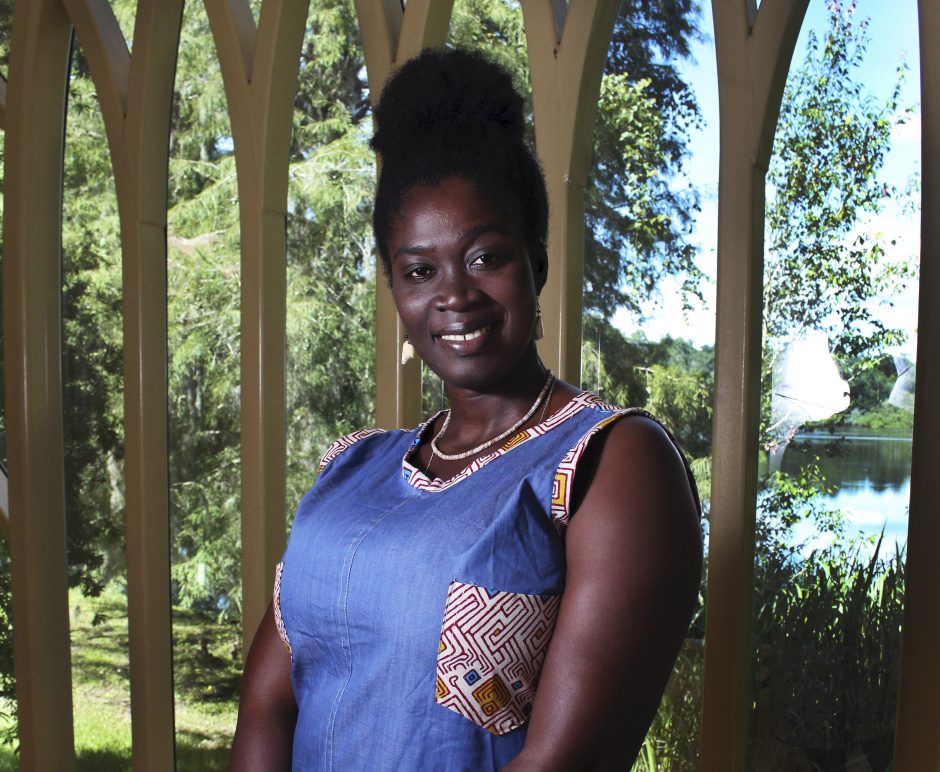

Selom Ametepe felt ready for the next step in her academic life. There was only one holdup.

A biologist from Lomé, Togo, a country in West Africa, Ametepe had been selected by the Institute of International Education for the 2018–19 Fulbright Junior Staff Development Program, allowing her to pursue graduate studies in the United States. But, her acceptance letter came with a catch: Her English wasn’t yet as strong as it would need to be to succeed in the program.

Many similar graduate programs and fellowships expect that international participants show a firm command of English before heading to a U.S. university. That’s where the English Language Institute (ELI) comes in.

Founded in 1954 and overseen by the Department of Linguistics in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the ELI is one of the oldest intensive English programs in the United States. Each semester, it welcomes hundreds of motivated students from around the world.

While some students are with the program for only one semester or six weeks, others intent on attending a U.S. college or university can spend half a year or longer studying with the ELI’s faculty and staff of language experts.

That was the case for Ametepe. With ELI’s training, she could pursue graduate studies in molecular biology and return to her home country with the necessary tools to address critical issues like food shortages and health issues. But first, she needed to prove that she had the English skills required by her preferred master’s degree program.

To do so, she would have to take the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL). The exam is scored on a scale of 0 to 120, and Ametepe, who was already fluent in French and Éwé, would need an 80 or better — though a high score wouldn’t necessarily guarantee her future success.

“A TOEFL score of 100 does not mean a student has any idea how to negotiate the higher education system in the U.S. or has the language skills to do so,” said ELI director MEGAN FORBES. Lack of these skills can bar an international student from finding an internship or a position in the United States.

With the ELI’s instruction, though, Ametepe would receive intensive training in a proven environment. Class sizes are small (no more than 15 students), and the ELI’s faculty teach the core skills of academic English along with how to succeed in the U.S. classroom setting, whose norms are often different from those of international universities. Students learn how to make polite requests, interrupt respectfully, debate controversial topics and understand American sarcasm — skills that native speakers often take for granted.

As a complement to their daytime studies, students can participate in the ELI’s Cultural Immersion Program (CIP) — “the first and most extensive” of any such program in the United States, according to Forbes.

CIP activities give international students opportunities to practice their English skills in social settings. Scheduled weekday activities include mixers at the Reitz Union, soccer and volleyball; weekend events feature group outings to Blue Springs, St. Augustine Beach, Disney World and other attractions in North and Central Florida.

Ametepe, meanwhile, was more concerned with studying for the test than socializing. She adjusted to the demands of practicing English 25 hours a week, plus preparing for the TOEFL and Graduate Records Examinations (GRE). Hunched over her books and laptop, Ametepe would study late into the evenings in Matherly Hall, where a quiet classroom let her focus better than she could in the busy libraries.

I can accomplish a lot of things to help my country, but to do that, I need credibility. With the master’s degree I am going to obtain, my voice now will be heard.

In Togo, she had taken the TOEFL twice and missed by more than 10 points, largely because of the speaking portion. At the time, Ametepe had spoken English the way it was written in her textbooks — formally. She reminded herself, “I am learning to speak daily English, not book English.”

When it came to writing, some of her instruction at ELI conflicted with the standards she had learned in Togo. A teacher, for instance, insisted that the students state their main ideas directly: “No beating around the bush.” That went against the grain of French academic writing, which favored long, ornate phrases.

After studying nonstop for almost three months, Ametepe took the TOEFL for the third time. Her nerves were wracked. So much was riding on this.

The results devastated her: 75. Five points short. “Maybe the Fulbright Program will not continue to fund me,” she worried to herself. “I will have to go back to Togo with no master’s degree.”

For the first time, though, her score on the TOEFL essay portion went up — significantly. She resolved to hold strong and try again.

Finally, after her fourth try, Ametepe received an 81, surpassing her target of 80 and allowing her to pursue her next degree at the University of Arkansas.

Ametepe plans to research how to maintain food safely and convert food waste into fertilizer — both useful for issues her country faces, as Togo produces abundant crops only to see much of it spoil quickly.

“I can accomplish a lot of things to help my country,” Ametepe said, “but to do that, I need credibility. With the master’s degree I am going to obtain, my voice now will be heard.”