Panorama of volcanic mountain full of colorful minerals in Iceland

Looking Deep Inside the Ancient Earth

With a mathematical time machine, UF geologist reconstructs what happened in the Earth’s interior 55 million years ago

Geologist ALESSANDRO FORTE is not shy about the ambitious nature of his recent research.

“In some sense, what we’re doing is almost an act of hubris,” he said. “We’re taking the laws of physics and reversing them.”

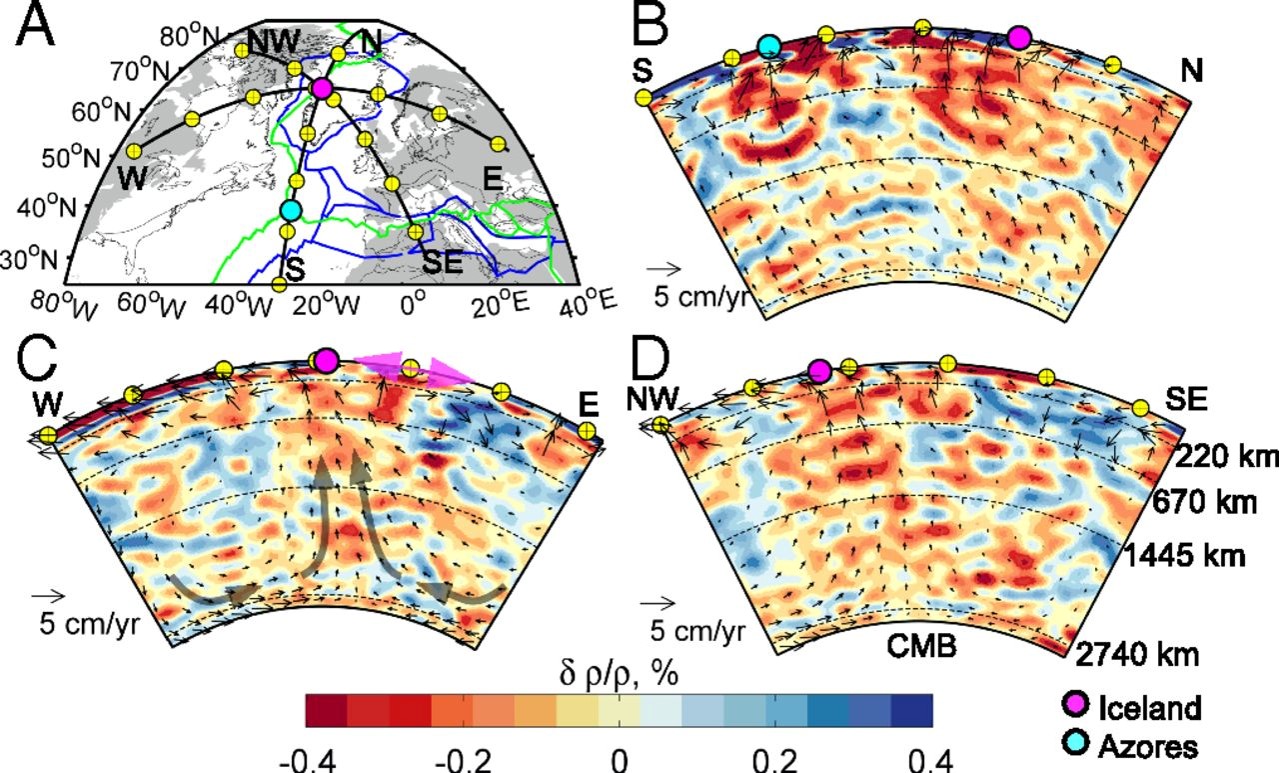

By that, Forte means that he and his collaborators are tracing the movement of heat backwards to see what the Earth’s interior looked like tens of millions of years ago. Using thermodynamic equations and present-day seismological data, the researchers create high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of ancient conditions deep below the Earth’s surface. Forte compared the result to a CAT scan, with geological features in place of bodily organs.

In a new study* led by Petar Glišović of Université du Québec à Montréal, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Forte reconstructed the phenomena occurring under the North Atlantic Ocean 55 million years ago that may have led to a period of rapid global warming.

During this period, known as the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), global temperatures are estimated to have increased by at least 5˚C, an escalation believed to be associated with a rise in greenhouse gases.

At the time, little permanent ice could exist on the Earth’s surface, and sea levels rose.

“The Earth went through essentially what I call a ‘fever,’” Forte said.

This era, though much hotter than today, interests many climate scientists as a possible warning of the conditions that could appear if humans continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Yet questions have remained about what caused the release of gases during the PETM — questions Forte and his team hope their new study will help resolve.

Many geologists suspect that as the North Atlantic Ocean widened 55 million years ago, volcanic activity pumped lava into hydrocarbon-rich rock, causing a rapid release of carbon dioxide and methane: “A greenhouse gas ‘burp,’” Forte called it.

With their maps, Forte and his team believe they have reconstructed sources of this volcanic activity: Two deeply-seated upwellings of hot rock underneath the earth’s surface. These “plumes,” the reconstructions show, reached all the way down to the boundary of the Earth’s mantle and core.

One of the plumes, then under Greenland and today under Iceland, has long been suspected to have played a role in the volcanic activity. But the importance of the second, found under the Azores — an archipelago about 850 miles west of Portugal — is a new discovery.

With the success of this work, Forte is eager to see what other parts of the Earth’s interior looked like 70 million years ago.

“We’ve taken on these difficult problems and produced these compelling images,” he said. “Now let’s start looking at what’s going on elsewhere.”