Petty Disputes, Serious Study

UF linguist studies why we bicker with those closest to us

At a typical Thanksgiving dinner, you can expect to find a few hallmarks: A golden brown roast turkey, globs of cranberry sauce and, of course, plenty of squabbling among family members.

Professor of Linguistics DIANA BOXER has put those holiday quarrels to good use in a new study focused on bickering. To collect data for the paper, students in her sociolinguistics course received an unusual assignment: Before they set off for Thanksgiving break in 2016, Boxer instructed them to take notes when they noticed anyone bickering — and when they participated in bickering themselves.

After repeating the assignment over the following semester’s spring break, Boxer ended up with 100 transcripts that detailed roommates spatting about unwashed dishes, siblings at odds over directions while driving, parents chiding their children for laziness and much more.

Bickering is usually defined as small, petty quarreling over trivial matters, but Boxer wanted to understand these arguments on a deeper level. The recorded exchanges offer a window into how these disputes crop up and play out between family members, romantic partners and close friends.

The subject of bickering is well within Boxer’s area of expertise: She often studies negative speech behaviors, previously taking on nagging, complaining, commiserating and boasting. By identifying the attributes that define each of these behaviors, she hopes to help people recognize them and head them off in their own lives.

“We can’t control much about what’s going on in the world around us,” she said. “But we can control what’s going on in our immediate environment by not participating in negative speech behaviors.”

Bickering, while usually short-lived and not very serious in the short-term, can end up eroding relationships when it accumulates.

“Over time, bickering can make people feel like a family member is a negative person who’s always picking on them,” Boxer said. “If we build more harmonious relationships we can be happier people.”

The Dance of Negotiation

In addition to analyzing her students’ field notes from their breaks, Boxer conducted a series of open-ended interviews with couples, pairs of coworkers and other subjects about their experiences with bickering. The aim of both parts of the study was to find what makes bickering distinct from similarly negative behaviors like complaining and arguing.

The resulting article was published in a special issue of the Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, co-edited by Boxer, that focused specifically on conflict in close personal relationships. In the paper, Boxer determines that bickering relies on “close social distance” — the participants need to know each other well enough that they abandon the niceties that hold back snide remarks.

“You don’t usually bicker with someone you don’t know very well because you’re trying to build solidarity,” she said. “But with family members you don’t bother to do that dance of negotiation, that back and forth to establish a relationship. I’m advocating that we should.”

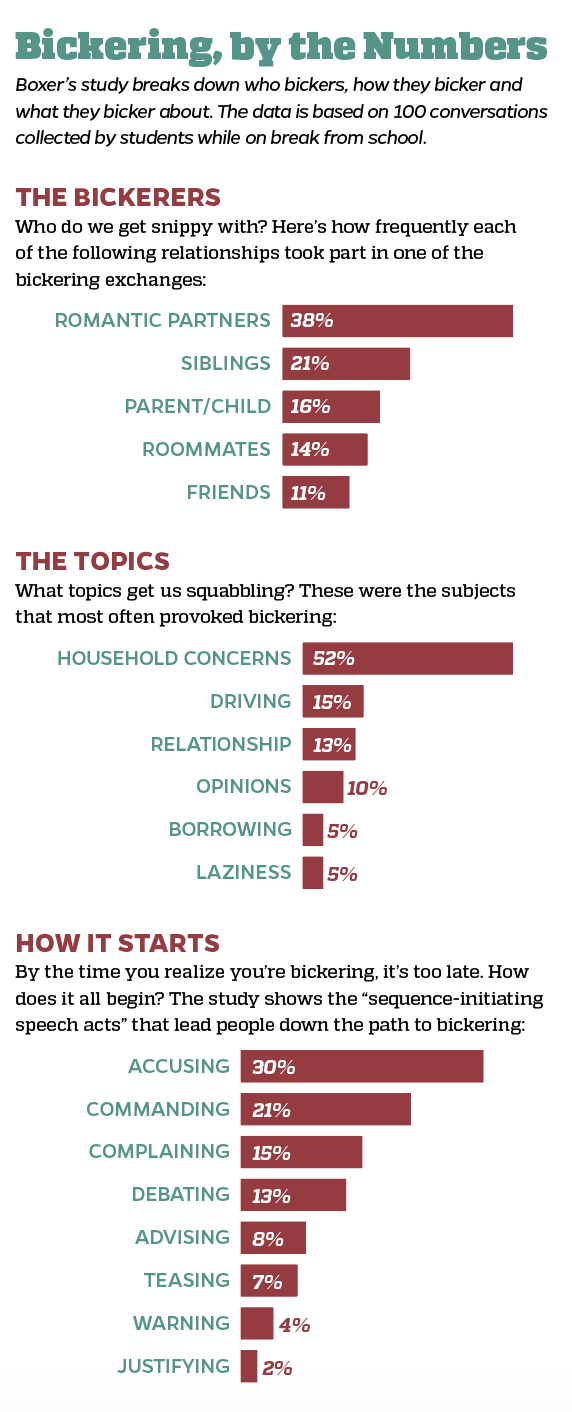

The study, which Boxer co-authored with graduate student JOSEPH RADICE, also identified common subjects that people bicker over (disputes over “household concerns,” such as cleaning the kitchen, made up over half of the examples), which relationships are most prone to bickering (perhaps unsurprisingly, romantic partners dominated at 38 percent), and the speech behaviors involved in bickering (accusations abounded, initiating 30 percent of the examples).

Boxer found that bickering has no benefits, as opposed to complaining, which can build solidarity among people in shared circumstances. People use bickering to air out “minor disagreements about relatively trivial topics,” the study concludes, but, unlike arguing, it “rarely escalates into verbal or physical violence.”

Conflict Begins at Home

So why study a type of conflict that is, by its very definition, trivial? While bickering might be insignificant on its own, minor conflicts in our close personal relationships set patterns for larger disputes throughout our lives.

“Conflict begins at home,” Boxer said. “If we are learning to be conflictive people with our families, that can translate into other spheres of life.”

Increasingly, she said, major conflicts with wide-ranging consequences — wars between nations, urgent political clashes or societal tensions — take precedence in research over studies about more intimate conflicts. Boxer thinks we shouldn’t overlook the small stuff.

“Family conflict has always interested me, and very little has been done about it,” she said.

The lack of such work motivated her to propose the special issue of the Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, which featured several articles about family conflict.

Not being a psychologist, Boxer is hesitant to give others advice about how to avoid bickering — but she hopes her findings offer researchers in other disciplines a starting point to build upon. She has already found the research useful in her own life. “With everything I study,” she said, “I learn what I shouldn’t do.”