Imagine the once-lush Planet Earth scorched across its surface, while the sublime beauty of the coastline has been subsumed by rocky shorelines comprising jagged remnants of once-valuable properties. Crops domesticated to be weather-hardy pale, while ubiquitous mosquitos find more refuge for their spawn and microscopic hitchhikers that ultimately make millions of humans sick.

This forecast of a bleak future is not so far off, says Terry Harpold, UF professor of English and expert in science fiction. In fact, he says, it has already begun. Yet in these changing times, as before, humans find solace in storytelling. Trained as a narratologist, Harpold applies his study of storytelling — particularly the ultimately prophetic genre of climate fiction — to environmental issues. He cautions against over-optimism that simple policy changes could undo the damage wrought in the post-Industrial Revolution era.

At the University of Florida, Harpold founded an interdisciplinary initiative, Imagining Climate Change, that offers a cultural means to work the problem, so to speak. Himself a storyteller, Harpold teaches his students that their lives and imagination are part of a humanistic endeavor beyond their immediate existence on the cusp of fundamental climate change. The imaginary began millennia ago with the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which a great flood swept the Earth, causing global devastation. Neither the Noah-like character Utnapishtim from Gilgamesh — nor the Bible’s Noah — could do anything but seek an absolution for their own journey through an environmental apocalypse.

We are already past the tipping point of 400 parts per million for carbon dioxide for climate change. On this point, scientists and storytellers agree, and also they share an appreciation for the imagination to creatively engage with reality. “Climate change is not just a physical phenomenon, it’s a cultural imaginary,” Harpold says. “It’s also a field of cultural endeavor, the way we understand our lives in the physical world incorporates the brute facts of physics and chemistry … but it also incorporates how we imagine what it means to be human in those environments, what it means to have families, what it means to have societies, to aspire to various futures, to perhaps mourn what’s passed — nay, the pasts.”

Harpold recalls Jean-Marc Ligny, a prolific author of science fiction who participated in the first year of Imagining Climate Change in 2015, explaining that he no longer had the breadth of possible future settings for his stories: climate change was too palpable a reality to escape.

Harpold has seen mild concern transform into dread, then into recognition, among his generations of college students. They are somewhat prepared by the trope of climate apocalypse in their so-called Young Adult fiction, with its sense of hopelessness as alarming as its predictions. And yet he has to break the news to them in every semester for any given climate fiction that “some version of this world is going to be your world.”

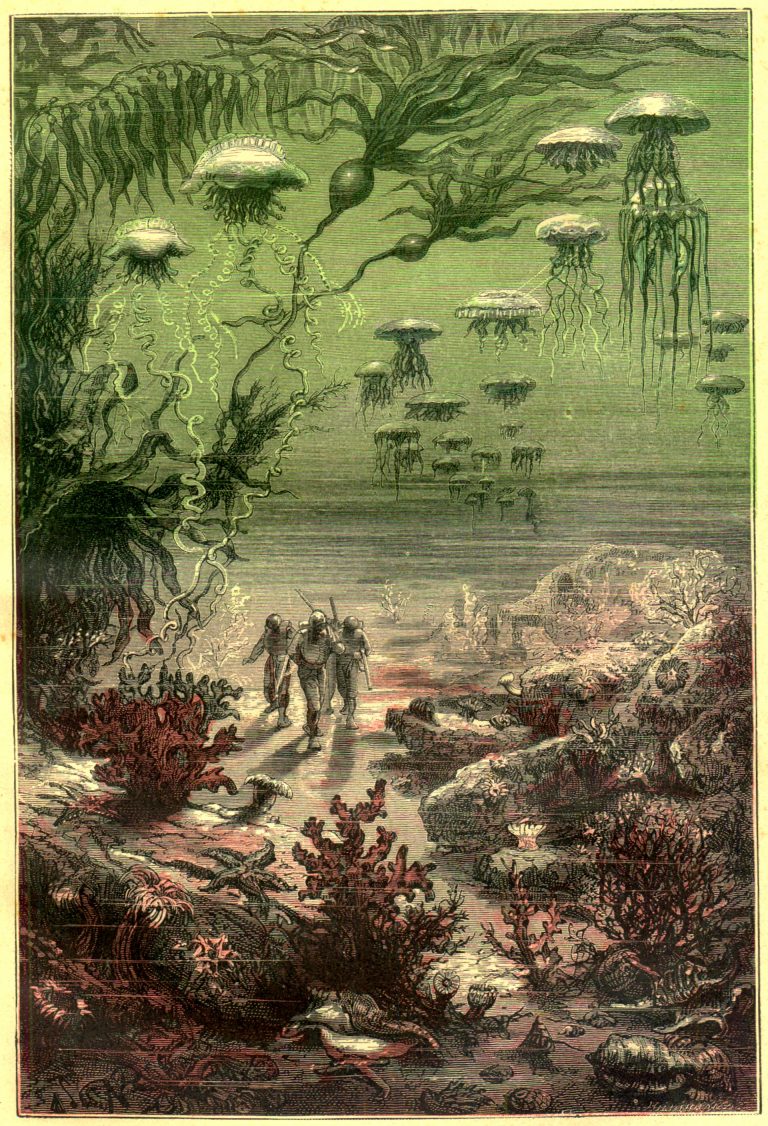

Illustration by Alphonse de Neuville for Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, Hetzel et Cie, 1869–70

Illustration by Alphonse de Neuville for Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, Hetzel et Cie, 1869–70“Science fiction is never about the future. It’s an alternative version of the present.”

He understands their anxiety. A member of the Jules Verne Society, Harpold focuses on 19th-century climate fiction, which only ever imagined as far as the year 2100. For those storytellers, 200 to 300 years seemed an eternity; to his students, climate fiction-turned-fact is within their lifetime. Generation Y and Z’s parents and grandparents imagined a world of eternally unfurling possibilities, without constraint or consequence. They had “a kind of go-go enthusiasm for a future without any kind of careful reflection on what they actually meant,” he says.

Science fiction, however, has always examined the sociocultural tensions in the face of bewildering changes. “The idea that Jules Verne and his contemporaries were mostly utopians looking forward to a golden age of technology, without constraint or consequence, just doesn’t jibe with what they actually wrote.”

Harpold’s students struggle with the plausibility of the bleak scenarios depicted in many of the books that he teaches. “Not everything we read depicts a dire and chaotic future,” he says. “There are climate fictions of positive transformation and hope. But we also read the relevant scientific literature, including research by some very fine climate scientists working at UF, and the students have no trouble connecting the dots.”

Harpold says that reflection — the “what if” — is increasingly embedded in and crucial to the “thought experiments” encapsulated in climate fiction. Climate crisis cannot be just “the purview of scientists and politicians,” he says. “It has to be addressed within a broad-ranging conversation that involves every aspect of human responses to the physical world.” Now more than ever, the “big questions” define the thirst of humanity and cannot be quenched by rising waters or rain-swept coasts. The brute facts lead to a brutal truth: There is no magic bullet, but to Harpold, imagination is itself a transformative tool. While we cannot wish the problem away, we can come to terms with our shared humanity. “I tell my students that despair and resignation are the refuge of cowards,” he says. “Literature can show us better ways forward.”

Societal fears and anxieties are well explored by science fiction. The sense of losing their footing in the grand vista of land, water, and sky is so disruptive that people seek answers in more than the headlines. As Cold War paranoia crept into zombie stories and genetic insecurity crept into mutant stories, so does the fear of being burned by the sky or swallowed by the ocean bleed into stories of catastrophic climate change.

“Science fiction is never about the future,” Harpold concludes. “It’s an alternative version of the present.”