Reimagining the Humanities

Now in its second decade, the Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere is bringing disciplines together to tackle grand-challenge questions

By Andrew Doerfler and Scott Rogers | Illustrations by Jim Harrison

Now in its second decade, the Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere is bringing disciplines together to tackle grand-challenge questions

By Andrew Doerfler and Scott Rogers | Illustrations by Jim Harrison

Now in its second decade, the Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere is bringing disciplines together to tackle grand-challenge questions

The humanities have a perception problem. Dogged by the recent sentiment that these disciplines favor ivory-tower indulgence over direct career paths, humanities scholars often feel the need to defend the value of their studies to the world. This won’t be the case for long. Today’s world faces unprecedented problems and questions — climate change, income inequality, racism and the role of technology in our lives — many of which can only be solved with help from the humanities.

At UF, the humanities find their home at the Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere. The center celebrated the 10th anniversary of its launch in April 2019 and is looking ahead to initiatives that could break new ground for the humanities across the nation.

Thanks to a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the center has been able to create a unique program aimed at tackling today’s most urgent issues through the humanities. UF Intersections: Animating Conversations with the Humanities allows faculty, doctoral students and staff from all corners of the humanities to come together and gives undergraduate students the chance to consider the questions that will define their lives.

“There are these grand intractable problems facing our world that can only be addressed by combining multiple forms of knowledge,” SOPHIA KRZYS ACORD, associate director of the center, said.

Intersections addresses four grand-challenge questions formulated by professors — from disciplines spanning African American studies, classics, religion, history and more — who usually wouldn’t have an opportunity to work so closely together. Each UF Mellon Intersections Group is conducting research and designing a cluster of courses on the topic while also planning events like speaker series to give students an opportunity to learn beyond the confines of the classroom.

This setup is something new for the field. “Collaboration in the humanities is something that is not entirely clear — there’s not a blueprint like there is in the sciences,” said BARBARA MENNEL, the Robert and Margaret Rothman Chair in the Humanities and director of the center.

While the Intersections questions vary, each group has similar goals — to expose students to diverse perspectives as they take on real-world challenges. Read on to learn more about each Intersections Group and see how the humanities will play a crucial role in shaping our world.

If you feel like it’s harder than ever to talk with one another about the most pressing issues facing society, you’re not alone.

It’s a big reason why one Intersections Group is using ethical reflection to take on hot-button topics like climate change, the #MeToo movement and income inequality. As the country grows more politically divided, the Intersections Group on Ethics in the Public Sphere, led by religion professor ANNA PETERSON and philosophy professor JAIME AHLBERG, wants to inspire more constructive conversations — and, hopefully, encourage meaningful action in the process.

“Even when something is really polarized, you can find points of common ground,” Peterson said. “But you have to be clear about what values are at stake.”

The approach has been on full display at the “ethics cafés” the group hosts on campus, where students are invited to discuss some of the most charged questions of the day. Asked what a just system of immigration in the United States would look like, more than 30 participants at a meeting followed a series of guidelines — stay on topic, don’t monopolize the conversation — as they sought points of agreement acknowledged what information they lacked and dug into the moral dimensions at play.

By calling attention to the ethical underpinnings of issues that dominate the news, this group hopes to make sometimes abstract philosophical, religious and moral questions feel urgent and relevant to students.

“Students want to learn about theory, but they also want to know how that stuff applies to their real lives,” Ahlberg said.

Peterson and Ahlberg have brought these questions to life in a class they teach on ethics in the public sphere, the idea for which formed the initial inspiration for the Intersections Group. Instead of lecturing, the professors try to create an environment where students come to their own conclusions through discussion, reflection and hands-on experience.

“STUDENTS WANT TO LEARN ABOUT THEORY, BUT THEY ALSO WANT TO KNOW HOW THAT STUFF APPLIES TO THEIR REAL LIVES.”

“People have to buy in and feel like they’re part of coming up with these answers,” Peterson said.

A class excursion to the Harn Museum of Art, for example, gave students a chance to explore the question of displaying the work of artists accused of sexual misconduct, as the museum grappled over a piece in its own collection by prominent painter and photographer Chuck Close.

The most heated class discussion came when the students were split into groups and given vastly different shares of candy, meant to represent strata of wealth — and then tasked with proposing a just economic system. ALARA GÜVENLI, an undergraduate student who took the course in spring, found the course made her more open to different points of view.

“Students can get stuck in their own bubbles where people agree with them,” she said. “But in the class, we all had to listen to each other — and a lot of people had opposing ideas.”

Peterson and Ahlberg also invited journalism librarian (and fellow Intersections Group member) APRIL HINES to the class for a presentation about finding reliable sources.

“Thinking well about complicated moral problems as they’re unfolding requires not just theorizing about values, but also knowing how to find and process empirical data,” Ahlberg said. “Good ethics needs good facts.”

A constructive conversation, though, isn’t an end unto itself: The goal, ultimately, is to encourage students to act to address the issues that matter most to them personally. Beginning in the spring 2020 semester, the Intersections Group will invite community organizations to campus for panel discussions to make students aware of the service and advocacy opportunities available in Gainesville.

The student body at a top-tier public university, Peterson said, presents an opportunity for the impact of this work to extend far beyond campus. “We have a diverse student body, and many first-generation college students,” Peterson said. “But these are also the people who go on to be the next professionals and leaders.”

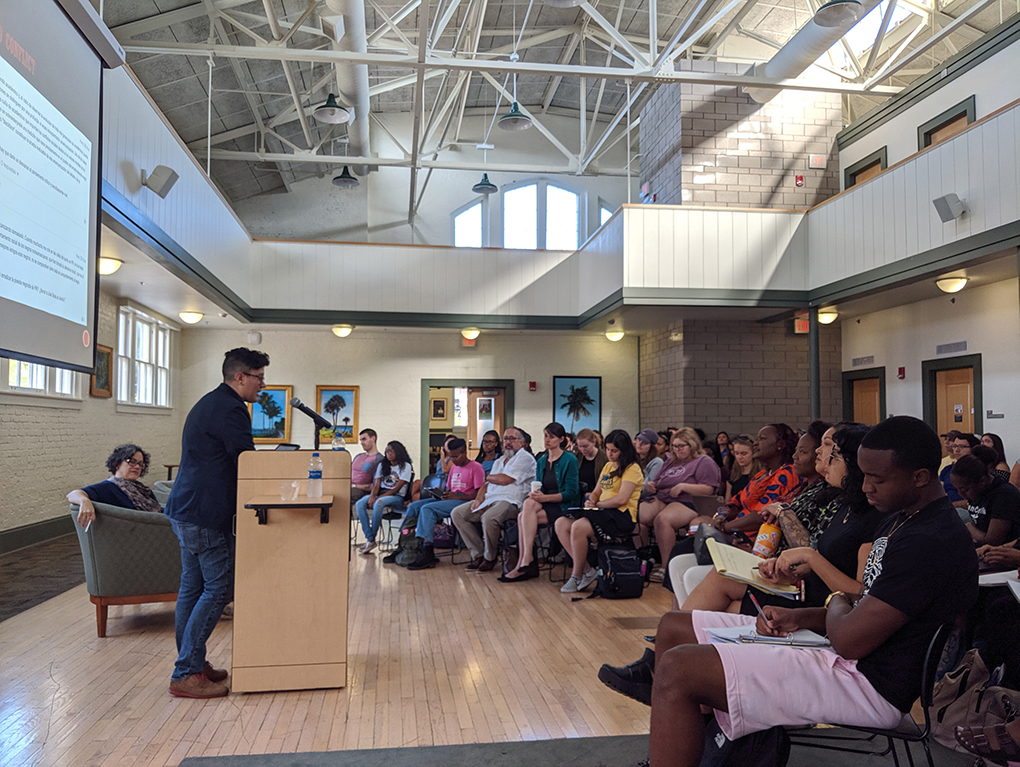

“Our students win when they are forced to stretch,” MANOUCHEKA CELESTE said.

A professor in the Center for Gender, Sexualities, and Women’s Studies Research and the African American Studies program, Celeste is also the convener for the Intersections Group on Global Blackness and Latinx Identity, which aims to help students broaden their worldview.

This group strives to answer a question far too often neglected in traditional curricula: How do Black and Latinx people shape our world?

To fill this gap, the Intersection Group has been working to expose students to histories and cultures they may not be familiar with through a mix of classroom experiences and events. “It’s about students really engaging with ideas and histories that they usually don’t encounter in other classes,” Celeste said.

“IT’S VERY EASY TO BE IN YOUR COMFORT ZONE AND TO BE WITH PEOPLE WHO ARE VERY SIMILAR TO YOU.”

“We need to prepare students to handle diversity,” said co-convener MARGARITA VARGAS-BETANCOURT, a librarian in the Latin American and Caribbean Special Collections. “Even students from underrepresented groups need to appreciate their cultural heritage.”

The Intersection Group’s year-long lecture series has brought speakers from varied backgrounds, including Nadève Ménard from the Université d’État d’Haïti, who examined Haiti’s complex linguistic landscape, and Aisha Durham from the University of South Florida, who discussed how artists like Erykah Badu and Missy Elliot are inviting us to reimagine hip-hop feminism.

For students from underrepresented groups, Celeste points to the power of seeing speakers and instructors who look like them and can speak to a shared life experience. “Students are hungry to see themselves represented and to talk about their experiences,” she said. “It makes them feel better about where they are at UF and also gives them a chance to imagine who they can be once they leave here.”

As the makeup of the country continues to become more diverse, this Intersections Group’s courses and events serve as an important touchpoint for a wide range of students.

“We want to explore in this time and era general aspects of immigration, of the diaspora of these groups to the U.S. but also the migration of these groups to Florida,” Vargas-Betancourt said.

In a globalized economy, students from all backgrounds need to know that after graduation they won’t necessarily be working with people who look exactly like them or who have had the same life experiences.

“It’s very easy to be in your comfort zone and to be with people who are very similar to you,” Vargas-Betancourt said. “It is challenging to be with people who are different from you.”

This Intersections Group offers complex experiences and encourages students to think broadly, finding connections across groups. These experiences can have a huge impact on not only their professional lives, but in their role as citizens of a rapidly changing world. “That’s how we equip all our students to go out in the world and do better, because they’re not shocked by reality,” Celeste said.

Students in the Intersections Group on Imagineering and the Technosphere will soon find themselves playing a board game — of sorts. At the start of the spring 2020 semester, they’ll receive a “game board,” essentially a satellite image of UF’s campus. This image will be broken down into grids, with several areas highlighted — Turlington Rock, Century Tower and a sculpture on display at the Harn Museum of Art are a few examples.

Students will then visit each location and, through their mobile devices, learn about items or buildings they have walked past a hundred times but likely never stopped to consider too deeply before.

What was the Century Tower used for in the past? How is it currently employed? And how might it be used in the future?

“As human beings we understand something better when we can see and touch it,” said ELENI BOZIA, the convener for this Intersections Group and an Assistant Professor of Classics and Digital Humanities. “We’re trying to help the students grasp ideas.”

The ultimate goal of the game is to give students firsthand experience on how we use technology to alter ourselves and our physical world.

The group’s definition of technology, though, encompasses far more than the latest iPhone. While their work does cover the impact of “literal technology” like mobile devices, computers and cars, it also dives into what Bozia calls “cultural technology.” Cultural technologies consist of constructs like language, art, politics and religious traditions — all created by humans, just like literal technologies. Together, these combine to help us define and organize our lives.

At the heart of this Intersections Group is the desire to show students that we are all more connected across cultures and even time than we think.

For example, when students play the “UF Quest Game,” they’ll stop by the Harn Museum of Art to take a look at a 17th century Korean bodhisattva sculpture and be compelled to consider the piece on a variety of levels.

What technology was used to make it? What purpose did it serve? What does it mean to them, the students, sitting in front of them here in Florida, thousands of miles away from where it was originally created, hundreds of years later?

“WE CAN OPEN THE STUDENTS TO THE IDEA THAT THIS IS EVERYBODY’S WORLD OUT THERE.”

Bozia and the fellow professors who make up this Intersections Group hope to uncover what the lessons of past inventions can teach us about how to address the problems facing humanity today — especially when we consider our current rapid rate of technological advances.

“I want to show the students a sense of continuation,” Bozia said, pointing out that the labels we put on life and history are often arbitrary. Ultimately, Intersections on Imagineering and the Technosphere hopes to show that more connects us than divides us. “We can open the students to the idea that this is everybody’s world out there,” Bozia said.

After students visit a location on the UF Quest Game board, they’ll receive a 3D-printed model of that location’s most identifiable trademark. These models will then be placed on the board until all pieces have been collected.

After years of skyrocketing detention rates made the U.S. prison population the largest in the world, the country’s decision makers have begun exploring ways to address mass incarceration. But despite the newfound attention to the issue, the Intersections Group on Mass Incarceration believes the conversation has been far too narrow. The team members aren’t just looking for ways to reduce prison populations, but to envision a society where justice doesn’t revolve around prison in the first place.

“A lot has been written about how we came to expand the prison system and develop the contemporary crisis of mass incarceration,” said English professor JODI SCHORB, the group’s convener. “But what’s next? That’s the bigger question. We have to transform how we think about those behind bars, who many think of as disposable and out of sight.”

The group believes there’s no single right way to address the issue. As an English professor, Schorb has explored the topic by teaching courses on convict writing and prison literature. A social scientist, meanwhile, will come at the issue another way — as will someone who has actually been incarcerated.

“Answering the question depends on researchers, activists and visionaries,” Schorb said. “You can’t undo the global entanglement of mass incarceration through policy changes alone. We have to imagine alternatives that don’t exist yet.”

But bringing together those invested in this issue from different disciplines and walks of life isn’t so easy. The resources provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation have allowed the team to further a conversation that might have remained fragmented.

“WE HAVE TO TRANSFORM HOW WE THINK ABOUT THOSE BEHIND BARS, WHO MANY THINK OF AS DISPOSABLE AND OUT OF SIGHT.”

To truly have an impact, the Intersections Group knows that it needs to involve those most immediately affected by mass incarceration.

They’ve put a major emphasis on elevating the community work being done off-campus — and in Gainesville, there’s no shortage of it, with organizations like the River Phoenix Center for Peacebuilding and the Legal Empowerment Advocacy Hub making local strides.

“We are all tangled up in mass incarceration in different ways, but we often fail to see it and how it negatively impacts our communities,” said STEPHANIE BIRCH, UF’s African American Studies librarian and the group’s co-convener.

Engaging undergraduates on this topic demands a variety of approaches, in part because students’ experiences vary so drastically.

“Some undergrads don’t often think about how prison and mass incarceration impact them,” Schorb said. “Others feel this every day, firsthand, in their families, homes and communities.”

The Intersections Group has held roundtable discussions that invite undergraduate students from different majors to share their perspectives on and experiences with the U.S. prison system, and they’ve even asked the students directly for their visions of what society would look like without mass incarceration. The pervasiveness of the prison system means that the topics can be linked to so many other facets of society.

“One of the ways we make mass incarceration relevant to students is by connecting it to other issues they may be concerned about — gender, race, labor, immigration, the environment, medical care,” Birch said. However, many students are already interested — their fall keynote lecture drew undergraduates studying a wide array of fields including classics, health and human performance, sociology and business.

UF, Schorb said, is uniquely positioned to make a difference by increasing attention on this issue. Not only can its status as a hub of research and learning lead to better policy, but its students leave with the tools to make an impact.

“These students graduate and go out in to the world. They vote, they volunteer,” she said. “They will drive the conversation forward.”

Undergraduate students who engage with one of the grand-challenge questions are named Intersections Scholars. Students receive this designation by taking three courses that address the grand-challenge question of their interest. This experience helps prepare them for a range of diverse careers through the program’s emphasis on critical thinking, research, creative problem-solving and intellectual curiosity.