Where History Happened

Educators take to the battlefields for a firsthand historical experience

By Sean Adams

Working as a historian keeps me in climate-controlled atmospheres — air-conditioned classrooms, comfortable offices, academic panels in staid hotel conference rooms and carefully maintained archives. In the summer of 2018, however, I purposely ventured out into the blast furnace that is western Florida and southern Alabama to see history firsthand, taking 36 teachers of elementary, middle and high school with me, plus a colleague.

The reason for this venture was a joint workshop by the Florida Humanities Council (opens in new tab) and the Alabama Humanities Foundation (opens in new tab) titled “The Civil War in the American South.” For the past five years, I’ve led teacher workshops that combine lectures and field trips to the site of the 1864 Battle of Olustee at Fort Clinch (opens in new tab) and the haunting slave cabins at Kingsley Plantation (opens in new tab) in Fernandina Beach.

The idea is to put teachers in the places where history happened so they can bring that experience back to their classrooms, where students might gain a new perspective on the past.

It’s one thing to read about the historical significance of these sites and quite another to put yourself behind the thick masonry walls at Fort Clinch, or to see the way that the white plastered slave cabins at Kingsley form a semicircle around the big house once occupied by Zephaniah and Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley. While no visit can do justice to understanding Zephaniah’s relationship with Anna, his African American wife, the plantation grounds offer an excellent example of the architecture of slavery.

Thanks to a generous gift from the HTR Foundation (opens in new tab) (an organization devoted to preserving American Civil War sites), we were able to bring teachers to Civil War sites around Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. Professor Lonnie Burnett, a Civil War historian, dean and associate provost at the University of Mobile, co-hosted this venture. Joined by teachers from Florida and Alabama, we began our exploration of the region in earnest with a trip to Fort Pickens, just south of Pensacola.

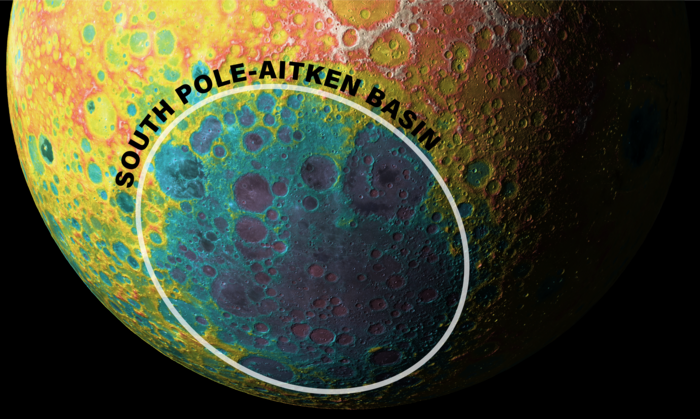

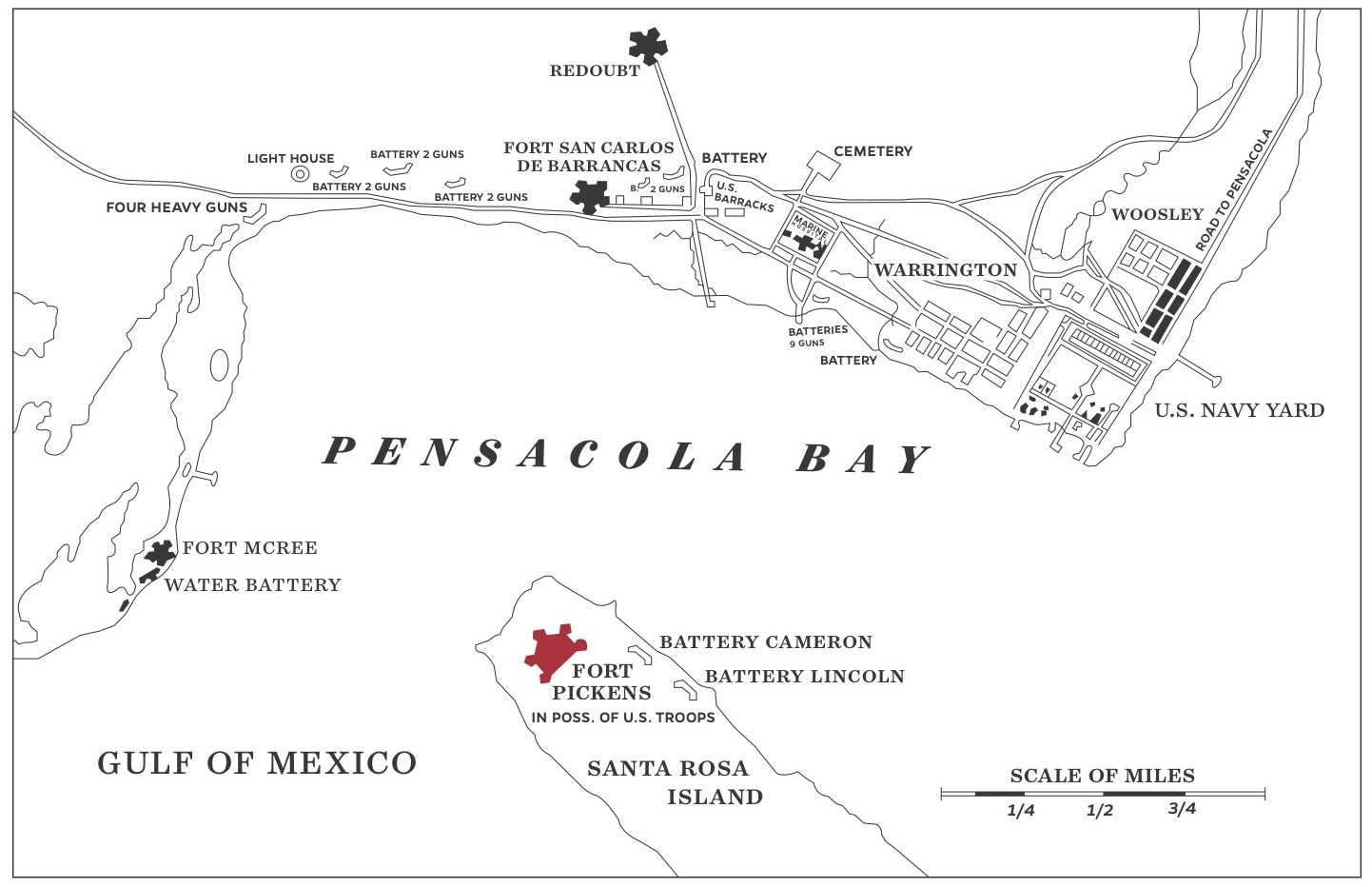

To get to Fort Pickens (opens in new tab), we took a bus from downtown to Santa Rosa Island and landed at Pensacola Beach. As we passed the condos and rental houses that haunt every Florida shore, the dive bars and beachside attractions became scarce. Urban sprawl was replaced by barren, sandy dunes, and we wound our way to Fort Pickens on the far western edge of the barrier island.

“There is something about being in these locations where the history we teach actually happens.”

The fort is a historical park now, so the guns are silent, but when the park ranger described the process of loading and firing each piece so that a constant barrage could be maintained, we easily imagined the heat, noise and turmoil of battle. When you’re deep inside the casement wall next to a massive artillery piece, it’s hard not to think about the tough job of the Union soldiers that lived and worked there. These men labored in a deafening furnace in 1861 — their ears bled from the explosions and most were severely concussed from the shockwaves.

A half century later, the teachers and I felt a connection to them. From atop the wall you can see the immense distance between Fort Pickens and Pensacola. Although Union and Confederate batteries launched salvo after salvo at each other in the early days of the conflict, few shells reached their targets. More fish than men were hurt in the opening battle of Florida’s Civil War. We came away from the visit with a pretty clear understanding of why Fort Pickens was not considered a choice assignment for the Union Army in the 1860s.

The following day, we took a walking tour of downtown Mobile, where the monuments to the city’s Mardi Gras traditions outnumber those to its Civil War past. Cars and trucks rumble down the same street where white Alabamans once celebrated the news that their state had seceded. Few structtures from that era remain, save some grand houses and churches. The modern city has overshadowed 19th century Mobile, and yet a glimpse of an old wooden balcony or a tall and weathered window pane reminds you that not every piece of the city’s history gave way to concrete and asphalt.

A visit to Historic Blakeley State Park (opens in new tab) on the east coast of the Mobile River delta capped off the workshop. At one point Blakeley sought to surpass its neighbor to the west, Mobile, as the premier city in South Alabama. In the early 1820s, Blakeley’s 4,000 or so residents could boast that they nearly doubled Mobile in size, and their deep-water port brought a consistent level of commerce. Yellow fever took its toll on the city, though, and eventually it became an abandoned ghost town.

Today, Blakeley is a state park, and the enthusiastic staff there is just beginning to embark on a reconstruction of its history. The town site itself is almost empty: Generations of thrifty Alabamans descended upon the depopulated buildings for free construction materials. The poor boomtown is now scattered in pieces across the region. Nature has reclaimed Blakeley — for now.

During the Civil War, however, the city’s fortunes were briefly revived as Confederates fortified Blakeley with 4,000 soldiers and extensive earthworks to protect the Mobile River. Fort Blakeley, like Fort Pickens, offers a great example of the significance of historical places. The Confederate lines are still visible, and the park has reconstructed some of the fortifications to look as they did during the 1860s.

The teachers and I marched up to the edge of the earthworks on a hot and muggy afternoon. It was probably cooler on April 9, 1865, when the 16,000 Union soldiers charged with capturing Fort Blakeley encountered its fortifications, but their immense task was still evident. Beginning about a thousand yards from the Confederate troops, Union forces first encountered roughly cut branches laid out to snag clothes and impede movement. They then passed between rows of sharpened sticks and slogged through water-filled trenches. After that, Confederate troops rolled out the cheval de frise — a defensive anti-cavalry device consisting of sharpened sticks radiating out from heavy logs — to further impede the Union forces. All the while, Confederate rifles and cannons raked the advance from behind thick walls of wood and earth.

We had a tame version of that advance in 2018, but after walking among these various impediments, we marveled at the courage of the average soldiers in 1865. And the fact that this battle took place on the same day as the Army of Northern Virginia’s surrender at Appomattox offers a somber reminder of the scope and severity of the Civil War. There’s really no substitute for seeing the spaces where history happened, and although it took some imagination and a great deal of sunscreen, the teachers and I saw the Civil War come alive in Florida and Alabama this summer.

“There is something about being in these locations where the history we teach actually happens,” one teacher wrote to us, “that makes it even more relevant to us and eventually our students.”

Photos and videos can’t re-create the stifling heat and humidity we faced in our various hikes, but we hope they can spark an interest in the past for a new generation of Floridians. To accomplish that, I’m more than happy to venture out from my everyday air-conditioned life as a professor at UF.

Sean Adams (opens in new tab) is the Hyatt and Cici Brown Professor of History at the University of Florida. He is the author of several books and specializes in the history of American capitalism and the history of energy.